Brief overview:

- Access to assistive technology (AT) is protected by four federal laws.

- The U.S. Department of Education has released guidance on the specific requirements about providing AT under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The guidance takes the form of detailed explanations for many misunderstood facts about using AT in schools and early intervention services. It is available online and in PDF form in English and Spanish.

- AT can be very simple and low-cost, or it may be high-tech or large and expensive. Resources for deciding on AT devices and services and buying or getting low-cost or free TA are included in the article.

Full Article

You can also type “assistive technology” in the search bar at wapave.org to find other articles where assistive technology is mentioned.

What is assistive technology (AT)? Who uses it? Where is it used?

Assistive technology (AT) is any item, device, or piece of equipment used by people with disabilities to maintain or improve their ability to do things. AT allows people with disabilities to be more independent in education, at work, in recreation, and daily living activities. AT might be used by a person at any age—from infants to very elderly people.

AT includes the services necessary to get AT and use it, including assessment (testing), customizing it for an individual, repair, and training in how to use the AT. Training can include training the individual, family members, teachers and school staff or employers in how to use the AT.

Some examples of AT include:

- High Tech: An electronic communication system for a person who cannot speak; head trackers that allow a person with no hand movement to enter data into a computer

- Low Tech: A magnifying glass for a person with low vision; a communication board made of cardboard for a person who cannot speak

- Big: An automated van lift for a wheelchair user

- Small: A grip attached to a pen or fork for a person who has trouble with his fingers

- Hardware: A keyboard-pointing device for a person who has trouble using her hands

- Software: A screen reading program, such as JAWS, for a person who is blind or has other disabilities

You can find other examples of AT for people of all ages on this Fact Sheet from the Research and Training Center on Promoting Interventions for Community Living.

Select the AT that works best:

Informing Families, a website from the Developmental Disabilities Administration, suggests this tip: “Identify the task first. Device Second. There are a lot of options out there, and no one device is right for every individual. Make sure the device and/or apps are right for your son or daughter and try before you buy.”

Understood.org offers a series of articles about AT focused on learning in school, for difficulties in math, reading, writing, and more.

Who decides when AT is needed? Your child’s medical provider or team may suggest the AT and services that will help your child with their condition. If your child is eligible for an Individualized Education Program (IEP), an Individualized Family Services Plan (IFSP), or a 504 plan, access to AT is required by law. In that case, the team designing the plan or program will decide if AT is needed, and if so, what type of AT will be tried. Parents and students, as members of the team, share in the decision-making process. A process for trying out AT is described on Center for Parent Information and Resources, Considering Assistive Technology for Students with Disabilities.

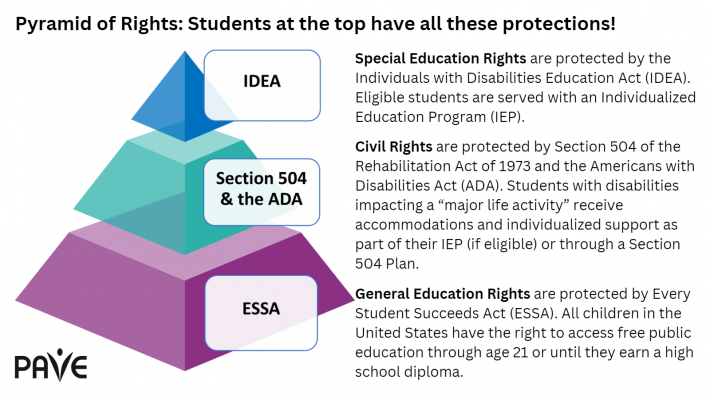

Access to assistive technology (AT) is protected by four laws:

- The AT Act of 2004 requires states to provide access to AT products and services that are designed to meet the needs of people with disabilities. The law created AT agencies in every state. State AT agencies help you find services and devices that are covered by insurance, sources for AT if you are uninsured, AT “loaner” programs to try a device or service, options to lease a device, and help you connect with your state’s Protection and Advocacy Program if you have trouble getting, using, or keeping an assistive service or device. Washington State’s AT agency, Washington Assistive Technology Act Program (WATAP), has a “library” of devices to loan for a small fee and offers demonstrations of how a device or program works.

- The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Part B protects the rights of pre-school through grade 12 students receiving special education to access and use AT as part of their Individualized Education Program (IEP) to ensure they get a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). The IEP team must consider AT every time they develop, review, or revise a student’s IEP (U.S. Department of Education 2024). Parents may also request evaluation by an assistive technology specialist to determine whether their student would benefit from AT.

IDEA Part C includes AT devices and services as an early intervention service for infants and toddlers, called Early Support for Infants and Toddlers (ESIT) in Washington State. AT can be included in the child’s Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). When a toddler transitions from early intervention services to preschool, AT must be considered whether or not a child currently has AT services through an IFSP.

It’s important that a student’s use of AT is specified in their post-secondary Transition Plan. This will document how the student plans to use AT in post-secondary education and future employment and may be needed when asking for accommodations from programs, colleges and employers when IDEA and IEPs no longer apply.

- Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, commonly called “Section 504, “is a federal law that protects students from discrimination based on disability.” This law applies to all programs and activities that receive funding from the federal government-including Washington public schools. Section 504 makes sure that students with disabilities have educational opportunities and benefits equal to those provided to students without disabilities. A student who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities may be protected by Section 504. A Section 504 Plan provides accommodations, aids, and services that students with disabilities need to access and benefit from education. According to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), “Section 504 requires that public schools provide a ‘free appropriate public education’ (FAPE) to every student with a disability – regardless of the nature or severity of the disability.”

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) includes the right to use assistive technology in public and government spaces, public schools and preschools, post-secondary education which receives federal funds (such as student loans) and in the workplace as a “reasonable accommodation”. You can find more information on specific ADA-related questions about AT at the Northwest ADA Center or the ADA website at the U.S. Department of Justice.

Guidance on assistive technology (AT) from the U.S. Department of Education

In January 2024, the U.S. Department of Education sent out a letter and guidance document on the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requirements for assistive technology for children under Part C and Part B of IDEA.

The guidance document is available online and in a downloadable pdf in English and Spanish. It includes common “Myths and Facts” about AT. The document is designed to help parents, early intervention providers, educators, related service providers, school and district administrators, technology specialists and directors, and state agencies understand what IDEA requires.

For instance, there are examples of what IFSPs might include:

- A functional AT evaluation to assess if an infant or toddler could benefit from AT devices and services;

- AAC devices (e.g., pictures of activities or objects, or a handheld tablet) that help infants and toddlers express wants and needs;

- Tactile books that can be felt and experienced for infants and toddlers with sensory issues;

- Helmets, cushions, adapted seating, and standing aids to support infants and toddlers with reduced mobility; and

- AT training services for parents to ensure that AT devices are used throughout the infant or toddler’s day.

For IEPs, some important facts from the guidance document are:

- Each time an IEP Team develops, reviews, or revises a child’s IEP, the IEP Team must consider whether the child requires AT devices and services (in order to receive a free appropriate public education (FAPE).

- If the child requires AT, the local educational agency (LEA) is responsible for providing and maintaining the AT and providing any necessary AT service. The IEP team can decide what type of AT will help the child get a meaningful educational benefit.

- The IEP must include the AT to be provided in the statement on special education, related services, and supplementary aids and services.

- A learner’s AT device should be used at home as well as at school, to ensure the child is provided with their required support.

- AT devices and services should be considered for a child’s transition plan as they can create more opportunities for a child to be successful after high school. (Note: AT can be an accommodation used in post-secondary education and in a job).

If a student is already using AT devices or services that were owned or loaned to the family, such as a smartphone, theguidance includes information about how to write it into an IEP or an agreement between the parents and school district.

Paying for AT

Some types of AT may be essential for everyday living including being out in the community and activities of daily living like eating, personal hygiene, moving, or sleeping. When a child has an AT device or service to use through an IFSP, IEP, or 504 plan, the device or service belongs to the school or agency, even if it’s also used at home. All states have an AT program that can help a school select and try out an AT device. These programs are listed on the Center for Assistive Technology Act Data Assistance (CATADA) website. A child’s AT devices and services should be determined by the child’s needs and not the cost.

When a child graduates or transitions out of public school, they may need or want AT for future education or work. In these cases, families can look for sources of funding for the more expensive types of AT. Here are some additional programs that may pay for AT devices and services:

- All five of Washington’s home and community-based service waiver programs available through the Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) provide access to AT for clients.

- The Community First Choice Program at DDA offers funding for AT.

- Northwest Access Fund offers low-cost AT loans.

- Informing Families has a page with many grants for getting low-cost assistive technology for all types of disabilities. The list focuses on resources in Washington State. Private insurance and Medicaid may cover AT required for medical reasons.

- Grants for AT for specific types of disability or special health need: check out the list at Informing Families, or reach out to organizations focused on different disabilities or health conditions.

AT for Military Families

Some programs specific to the United States Armed Forces may cover certain types of assistive technology as a benefit.It’s important for Active-Duty, National Guard, Veteran and Coast Guard families to know that they are eligible for assistive technology programs that also serve civilians, including those in Washington State.

If the dependent of an Active-Duty servicemember is eligible for TRICARE Extended Care Health Option (ECHO), assistive technology devices and services may be covered with some restrictions. The program has an annual cap for all benefits and cost-sharing, so the cost of the AT must be considered. The AT must be pre-authorized by a TRICARE provider and received from a TRICARE-licensed supplier. If there is a publicly funded way to get the assistive technology (school, Medicaid insurance, Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Waiver, state AT agency loaner device, or any source of taxpayer-funded access to AT), the military family must first exhaust all possibilities of using those sources before ECHO will authorize the AT.

Some types of AT, such as Durable Medical Equipment, may be covered under a family’s basic TRICARE insurance plan.

The United States Coast Guard’s Special Needs Program may include some types of assistive technology as a benefit.

Additional Resources

Assistive Technology

Does my child qualify for Assistive Technology (AT) in school?

Low tech tool ideas that can be used to increase Healthcare Independence