Caring for individuals with disabilities or complex medical needs can be emotionally and physically draining, making intentional self-care essential for long-term well-being. Simple practices like mindfulness, getting enough sleep, going for a walk, or taking a few deep breaths can help reduce stress and build resilience. Talking to others who understand and finding time to rest can also help caregivers stay strong and healthy.

A Brief Overview

- Self-care is not selfish. Self-care is any activity or strategy that helps you survive and thrive in your life. Without regular self-care, it can become impossible to keep up with work, support and care for others, and manage daily activities.

- PAVE knows that self-care can be particularly challenging for family members caring for someone with a disability or complex medical condition. This article includes tips and guidance especially for you.

- PAVE provides a library with more strategies to cultivate resilience, create calm through organization, improve sleep, and more: Self-Care Videos for Families Series.

Introduction

Raising children requires patience, creativity, problem-solving skills and infinite energy. Think about that last word—energy. A car doesn’t keep going if it runs out of gas, right? The same is true for parents and other caregivers. If we don’t refill our tanks regularly we cannot keep going. We humans refuel with self-care, which is a broad term to describe any activity or strategy that gives us a boost.

Self-care is not selfish! Without ways to refresh, we cannot maintain our jobs, manage our homes, or take care of people who need us to keep showing up. Because the demands of caring for someone with a disability or complex medical condition can require even more energy, refueling through self-care is especially critical for caregivers.

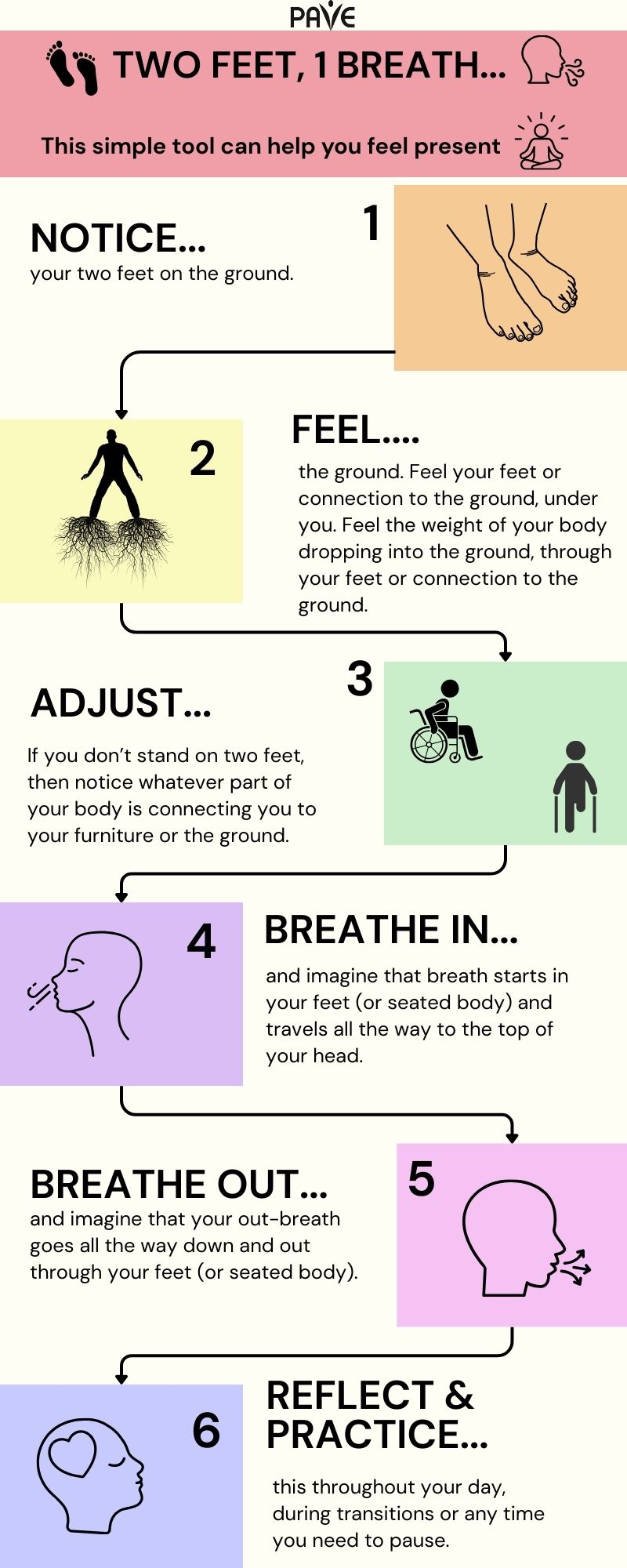

Two Feet, One Breath

Before you read anymore, try this simple self-care tool called Two Feet, One Breath. Doctors use this one in between seeing patients.

Download this infographic, Two Feet 1 Breath:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Two Feet, One Breath can become part of every transition in your day: when you get out of bed or the car, before you start a task, after you finish something, or any time you go into a different space or prepare to talk with someone. This simple practice highlights how self-care can become integrated into your day.

Although a day at the spa might be an excellent idea, self-care doesn’t have to be fancy or expensive to have a big impact!

Almost everyone knows or cares for someone with special needs. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), at least 28% of the American population experiences a disability. The result is widespread compassion fatigue, which is a way to talk about burnout from giving more than you get.

Below are some ways to use self-care to avoid burnout!

Connect with others

Building a support network with others who share similar life experiences can be incredibly valuable. When you’re going through a challenging or unique situation—like parenting a child with special needs or managing a family health issue—it can feel isolating. These connections offer emotional validation and a sense of understanding that can be hard to find elsewhere—you don’t have to explain everything because others simply get it. Research shows that social support can significantly reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, enhancing overall well-being and resilience. Beyond emotional comfort, support networks empower individuals by helping them build confidence, understand their rights, and even engage in advocacy efforts that benefit their families and communities.

Here are some communities and resources to help you get connected:

Parent-to-Parent Connections

The Parent-to-Parent network can help by matching parents with similar interests or by providing regular events and group meetings.

Support for Families of Youth Who Are Blind or Low Vision

Washington State Department of Services for the Blind (DSB) offers resources and support for families. You can also hear directly from youth about their experiences in the PAVE story: My story: The Benefits of Working with Agencies like the Washington State Department of Services for the Blind.

Support for Families of Youth Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing

Washington Hands and Voices offers opportunities for caregivers of youth who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHH) to connect, share experiences, and find community.

Resources for Families Navigating Behavioral Health Challenges

Several family-serving organizations provide support, education, and advocacy for caregivers of children and youth with behavioral health conditions:

- Family, Youth, and System Partner Round Table (FYSPRT). Regional groups are a hub for family networking and emotional support. Some have groups for young people.

- Washington State Community Connectors (WSCC). WSCC sponsors an annual family training weekend, manages a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Family Navigator training, and offers ways for families to share their experiences and support one another.

- COPE (Center of Parent Excellence) offers support group meetings and direct help from lead parent support specialists as part of a statewide program called A Common Voice.

- Dads Move works to strengthen the father’s role in raising children with behavioral health needs through education, peer support and advocacy.

- Healthy Minds Healthy Futures is an informal network on Facebook.

PAVE provides a comprehensive toolkit for families navigating behavioral health systems, including guidance on crisis response, medical care, education, and family support networks.

Get Enough Sleep

The body uses sleep to recover, heal, and process stress. If anxiety or intrusive thinking consistently interrupts sleep, self-care starts with some sleeping preparations:

- Turn off screens after 7 pm, or use a blue-light filter

- Pre-load sleepy music or a calming meditation onto your phone or tablet

- Finish the evening with an herbal tea, such as chamomile

- Check out PAVE’s video: Body Sensing Meditation for Help with Sleep

- For more ideas, visit SleepFoundation.org

Move Your Body

Moving releases feel-good chemicals into the body, improves mood, and reduces the body’s stress response. Walk or hike, practice yoga, swim, wrestle with the kids, chop wood, work in the yard, or start a spontaneous living-room dance party.

The Mayo Clinic has this to say about exercise:

- It pumps up endorphins. Physical activity may help bump up the production of your brain’s feel-good neurotransmitters, called endorphins. Although this function is often referred to as a runner’s high, any aerobic activity, such as a rousing game of tennis or a nature hike, can contribute to this same feeling.

- It reduces the negative effects of stress. Exercise can provide stress relief for your body while imitating effects of stress, such as the flight or fight response, and helping your body and its systems practice working together through those effects. This can also lead to positive effects in your body—including your cardiovascular, digestive and immune systems—by helping protect your body from harmful effects of stress.

- It’s meditation in motion. After a fast-paced game of racquetball, a long walk or run, or several laps in the pool, you may often find that you’ve forgotten the day’s irritations and concentrated only on your body’s movements. Exercise can also improve your sleep, which is often disrupted by stress, depression and anxiety.

Be Mindful

Mindfulness can be as simple as the Two Feet, One Breath practice described at the top of this article. Mindfulness means paying attention or putting your full attention into something. Focusing the mind can be fun and simple and doesn’t have to be quiet, but it should be something that you find at least somewhat enjoyable that requires some concentration. Some possibilities are working on artwork, cleaning the house or car, crafting, working on a puzzle, cooking or baking, taking a nature walk, or building something.

For more mindfulness ideas, check out PAVE’s Mindfulness Video Series. From this playlist, Get Calm by Getting Organized, explores how getting organized provides satisfaction that releases happiness chemicals and hormones.

Schedule Time

A day can disappear into unscheduled chaos without some intentional planning. A carefully organized calendar, with realistic boundaries, can help make sure there’s breathing room.

Set personal appointments on the calendar for fun activities, dates with kids, healthcare routines, and personal “me time.” If the calendar is full, be courageous about saying no and setting boundaries. If someone needs your help, find a day and time where you might be able to say yes without compromising your self-care. Remember that self-care is how you refuel; schedule it so you won’t run out of gas!

Time management is a key part of stress management! This article, “Stress Management: Managing Your Time” from Kaiser Permanente, gives tips for managing your time well, so you can reduce the pressure of last-minute tasks and make space for the things that matter most to you.

Seek Temporary Relief

Respite care provides temporary relief for a primary caregiver. In Washington State, a resource to find respite providers is Lifespan Respite. PAVE provides an article with more information: Respite Offers a Break for Caregivers and Those They Support.

Parents and caregivers of children with developmental disabilities can seek in-home personal care services and request a waiver for respite care from the Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA). PAVE provides two training videos about eligibility and assessments for DDA. For more information about the application process, Informing Families provides a detailed article and video.

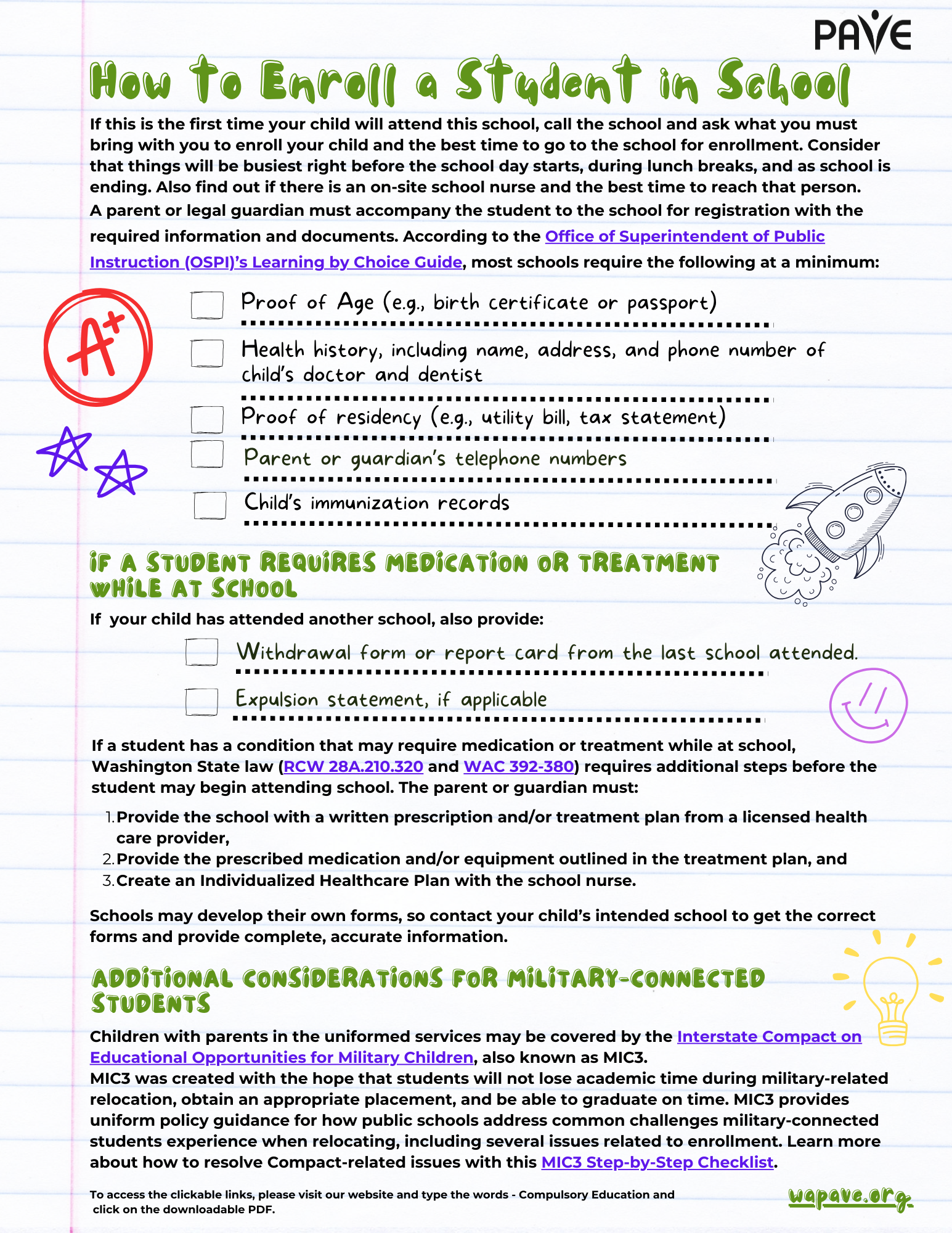

Download the Emotional Wellness Tips for Caregivers

Download this checklist of Emotional Wellness Tips for Caregivers in:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt