Data plays a crucial role in special education, helping teachers, parents, and support teams create effective learning plans for students with disabilities. By understanding data, students and their families can work together with educators to ensure students successfully reach their educational goals.

Brief Overview

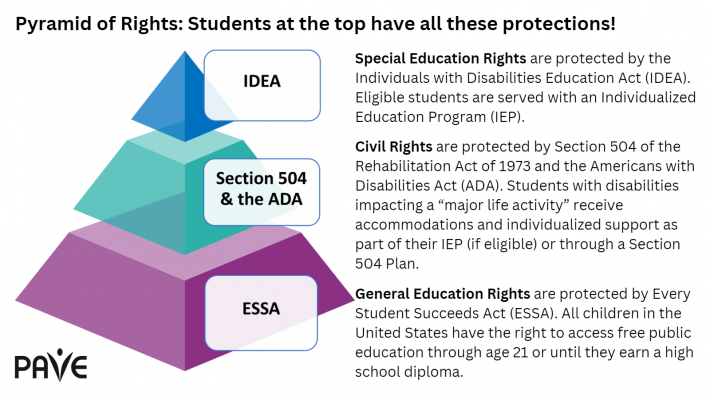

- Data includes information on a student’s learning, behavior, and progress from various sources, used to develop Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or Section 504 plans.

- Data helps set learning goals, choose strategies, and decide on accommodations, with regular reviews to adjust plans.

- Data helps parents and students advocate for support, track progress, and request extra services if needed.

- This article contains descriptions of the various types of data, test scoring systems, and assessments commonly used in special education.

- If families and school districts disagree about evaluation data, there are procedural safeguards to help resolve disputes.

What is Data in Special Education?

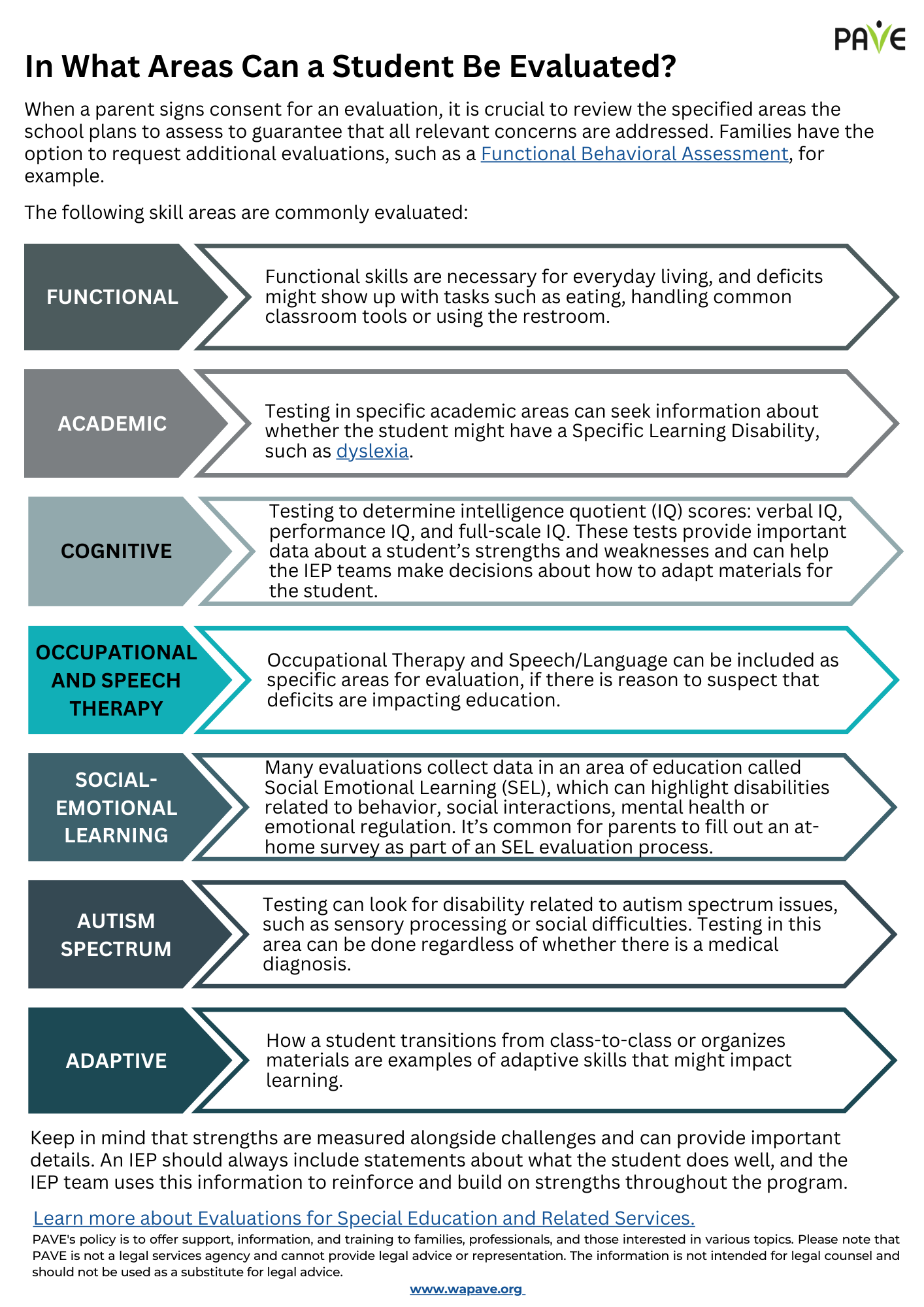

Data is any information collected about a student’s learning, behavior, and progress. It can come from test scores, classroom performance, teacher observations, and feedback from parents and students. This information is used to develop an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or a Section 504 plan that meets the student’s unique needs.

Types of Data Used in IEPs

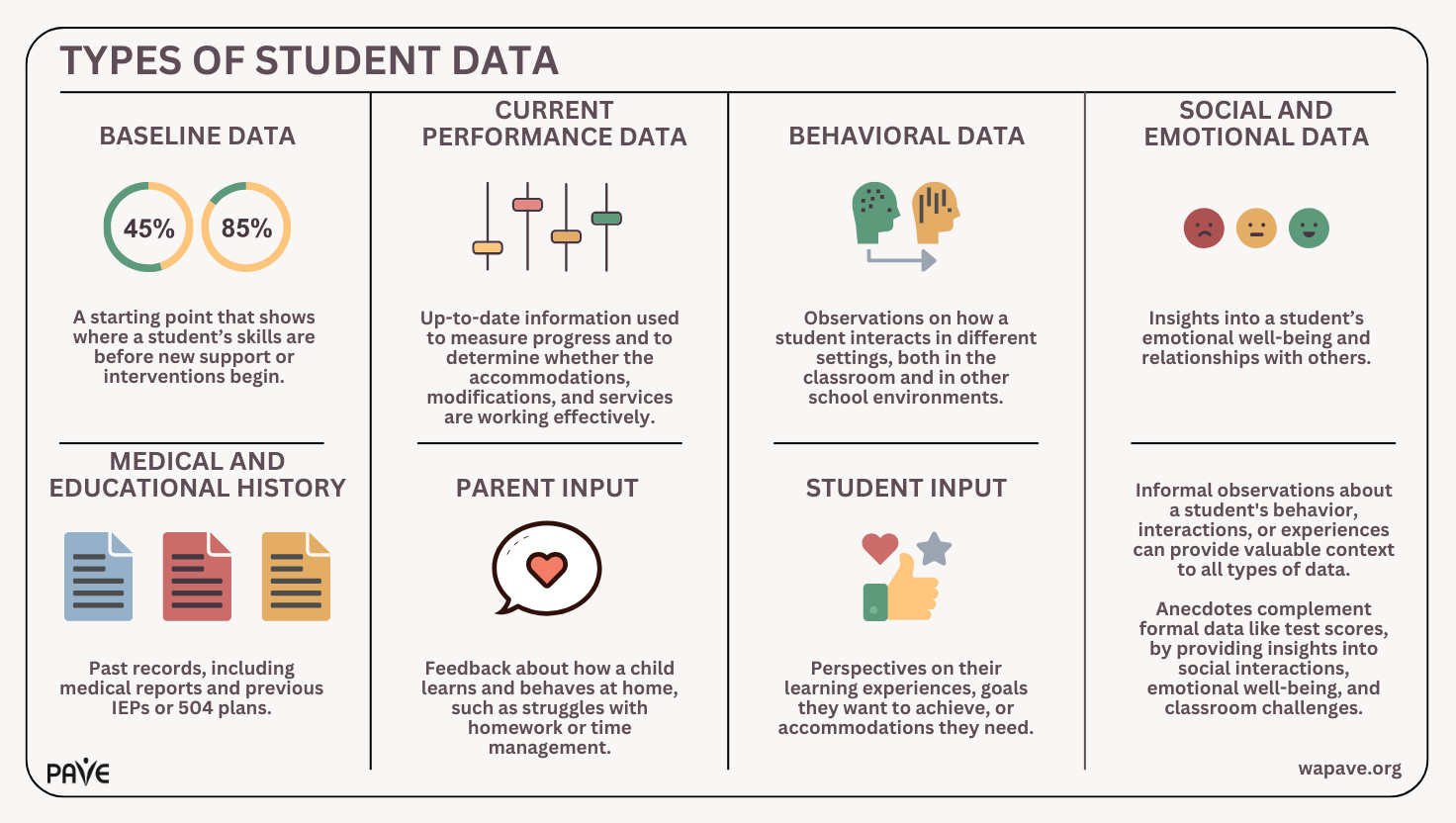

IEP and Section 504 teams use different types of data to understand a student’s abilities and challenges. These include:

- Baseline Data: A starting point that shows where a student’s skills are before new support or interventions begin. This could include initial test scores, observations of classroom behavior, and assessments of academic abilities such as reading fluency or math skills. Baseline data is crucial because it helps educators and parents track how the student progresses over time.

- Current Performance Data: Up-to-date information used to measure progress and to determine whether the accommodations, modifications, and services are working effectively. Performance data includes recent test scores, progress and grade reports, class assignments and homework, and observations from IEP or 504 team members. Teachers and staff might also track how often a student completes assignments or engages with the material being taught.

- Behavioral Data: Observations on how a student interacts in different settings, both in the classroom and in other school environments. It can include records of behavioral incidents, such as disruptions or outbursts, as well as observations on how the student interacts with peers and follows classroom routines. Behavioral data helps identify patterns and triggers for specific behaviors, which can be addressed with strategic interventions.

- Social and Emotional Data: Insights into a student’s emotional well-being and relationships with others. This type of data helps to understand how the student is managing relationships, emotional regulation, and any challenges they may be facing in terms of anxiety, stress, or peer interactions. Information may come from school counselors, social workers, or teacher reports on the student’s ability to work in groups or handle stress in academic settings.

- Medical and Educational History: Past records, including medical reports and previous IEPs or 504 plans. These records help educators understand what interventions have been tried before, what worked, and what didn’t. They also give context to the student’s academic performance over the years and may provide insight into any ongoing health conditions that might affect their learning.

- Parent and Student Input: Parents often provide important feedback about how their child learns and behaves at home, such as struggles with homework or time management, which can complement academic performance data. Students themselves can share their perspectives on their learning experiences, goals they want to achieve, or accommodations they need, helping ensure the plan aligns with their needs.

Informal observations about a student’s behavior, interactions, or experiences can provide valuable context to all types of data. These anecdotes from parents, students, teachers, or service providers offer personal accounts of how a student responds to situations or interventions. By complementing formal data like test scores, these observations provide insights into social interactions, emotional well-being, and classroom challenges. This helps to understand the student’s strengths and areas for growth. When combined with formal data, anecdotal feedback creates a more comprehensive and effective educational plan tailored to the student’s needs.

Using Data to Customize Student Supports

An IEP or 504 plan is created based on data collected through evaluations and observations. This information helps set learning goals, choose instructional strategies, and decide on accommodations and services. For example, if a student struggles with reading, data can show whether the challenge lies in comprehension, vocabulary, or decoding words.

The IEP or 504 team, including parents, teachers, and specialists, meets regularly to review data and adjust the IEP or 504 plan as needed to ensure they remain effective. Under Washington Administrative Code (WAC 392-172A-03015), students with IEPs must be re-evaluated at least once every three years, though parents or educators can request more frequent assessments if needed. Data for IEPs must be reviewed at least annually to determine whether the student’s goals and services need to be updated (WAC 392-172A-03110(3)).

The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) has outlined the requirements for review and reevaluation of 504 plans in the Students’ Rights Information Sheet: Section 504, a document available for download in multiple languages on the OSPI website. School districts must re-evaluate a student’s eligibility for a 504 plan at least every three years and review the 504 plan annually to ensure that it continues to be effective. Parents or teachers can request a review at any time.

Understanding Test Scores

Test scores provide important insights into a student’s learning progress. Scoring systems vary, and the results can be presented in different formats. Some common types include:

- Raw scores indicate the number of correct answers or tasks completed correctly. For example, if a student correctly answers 35 out of 40 questions, their raw score is 35.

- Standard scores compare a student’s performance to others of the same age, with 100 as the average. The mean is the average score, and the standard deviation shows how much the scores vary from that average. With a standard deviation of 15 on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V), most students’ scores will fall between 85 and 115, and scores further from 100 indicate greater differences from the average.

- Percentile ranks show where a student’s performance ranks in comparison to their peers. If a student is in the 70th percentile, they scored higher than 70% of their peers statewide. A score in the 30th percentile means the student scored higher than 30% of other students.

- Age and grade equivalent scores show how a student’s performance compares to typical expectations for their age or grade. A 5th-grade student with a grade equivalent score of 7.0 is performing at the level expected of an average 7th grader.

Types of Assessments

There are two main types of tests used in special education: norm-referenced and criterion-referenced. Norm-referenced tests compare a student’s performance to other students in the same age group or grade level. For example, an IQ test measures a child’s cognitive abilities compared to others of the same age by assessing areas like verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, working memory, and processing speed. Criterion-referenced tests measure how well a student has learned specific skills. Classroom-based assessments are often criterion-referenced tests, like a math test that focuses on a student’s ability to accurately complete addition and subtraction problems. The Smarter Balanced Assessments (SBA) are English language arts (ELA) and math tests given to students in grades 3-8 and 10. The SBA is both a norm-referenced assessment, comparing student performance to state and national benchmarks, and a criterion-referenced assessment, measuring students’ mastery of skills needed for graduation and academic progress.

Using Data to Advocate for Student Needs

Data helps parents and students advocate for the right support. If test scores show that a student is falling behind, families can use this information to request extra services, such as tutoring or assistive technology. Data also helps track progress to see if current strategies are working or if changes are needed.

Asking questions about the data can help parents and guardians better understand their child’s needs and ensure they are getting the right support. By engaging in these conversations, parents can advocate for their child more effectively and make sure their progress is being tracked accurately. Here are some helpful questions to ask during meetings with the IEP or 504 team:

- Can you show me the data that supports this change in supports or services?

- What specific data or assessments have been used to understand my child’s academic performance?

- How do my child’s scores compare with other students in their age group or grade level?

- What scoring type was used to determine these evaluation results?

- Can you explain how the data indicates where my child might need additional support?

- Based on the test scores and data, what are my child’s strengths and how can we use them to improve their weaknesses?

- How often will we review the data to see if my child is making progress? Will there be ongoing assessments and, if so, which assessments will be used?

Resolving Disagreements over Evaluation Data

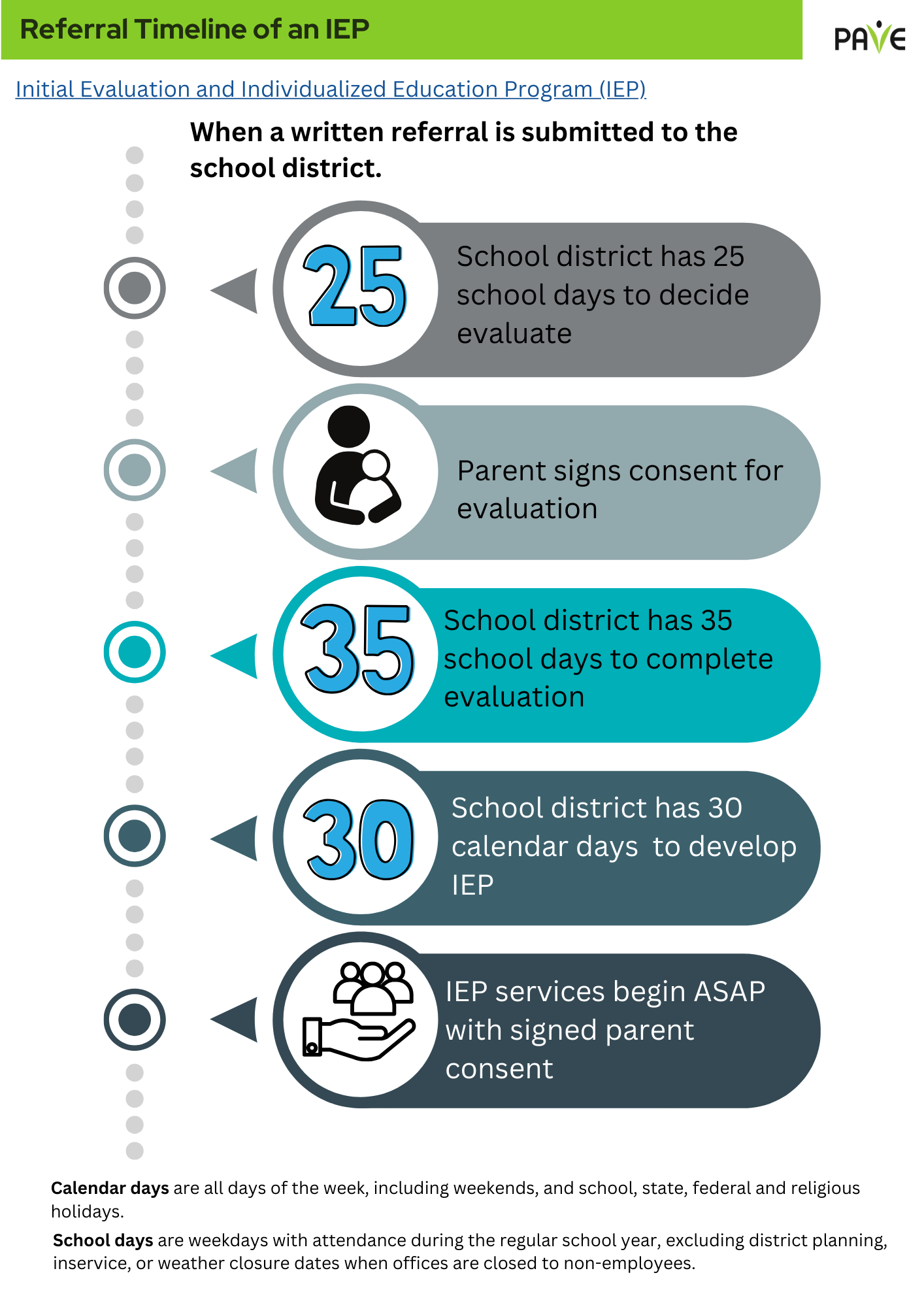

Procedural Safeguards outline the evaluation process and the dispute resolution options when families and school districts disagree about evaluations. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), parents have the right to request an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE). The IEE must be requested in writing and PAVE provides a Sample Letter to Request an IEE paid for at public expense by the school district. If the request is approved, the school district provides a list of independent evaluators. The school must consider the IEE results when determining the student’s eligibility for special education services. If the school district denies the request for an IEE, it must start a due process hearing within 15 calendar days to justify its evaluation. Parents have the right to request an IEE anytime a student is evaluated and they disagree with the result.

According to Section 504 Notice of Parent Rights, downloadable in multiple languages on the OSPI website, parents have the right to request mediation or an impartial hearing, if they disagree with the school district’s identification, evaluation, educational program, or placement.

Final Thoughts

Data plays a powerful role in shaping IEP and 504 plans for students with disabilities. By using detailed information from various sources, educators, parents, and support teams can create personalized and effective plans that meet each student’s unique needs. Understanding and using data empowers students and parents to take an active role in education, working closely with teachers and specialists to ensure that students receive the right support to succeed in school and beyond.