If you are a student with an Individualized Education Program (IEP), read this article to find out how you can be a leader on your IEP team. Your future is counting on you!

A Brief Overview

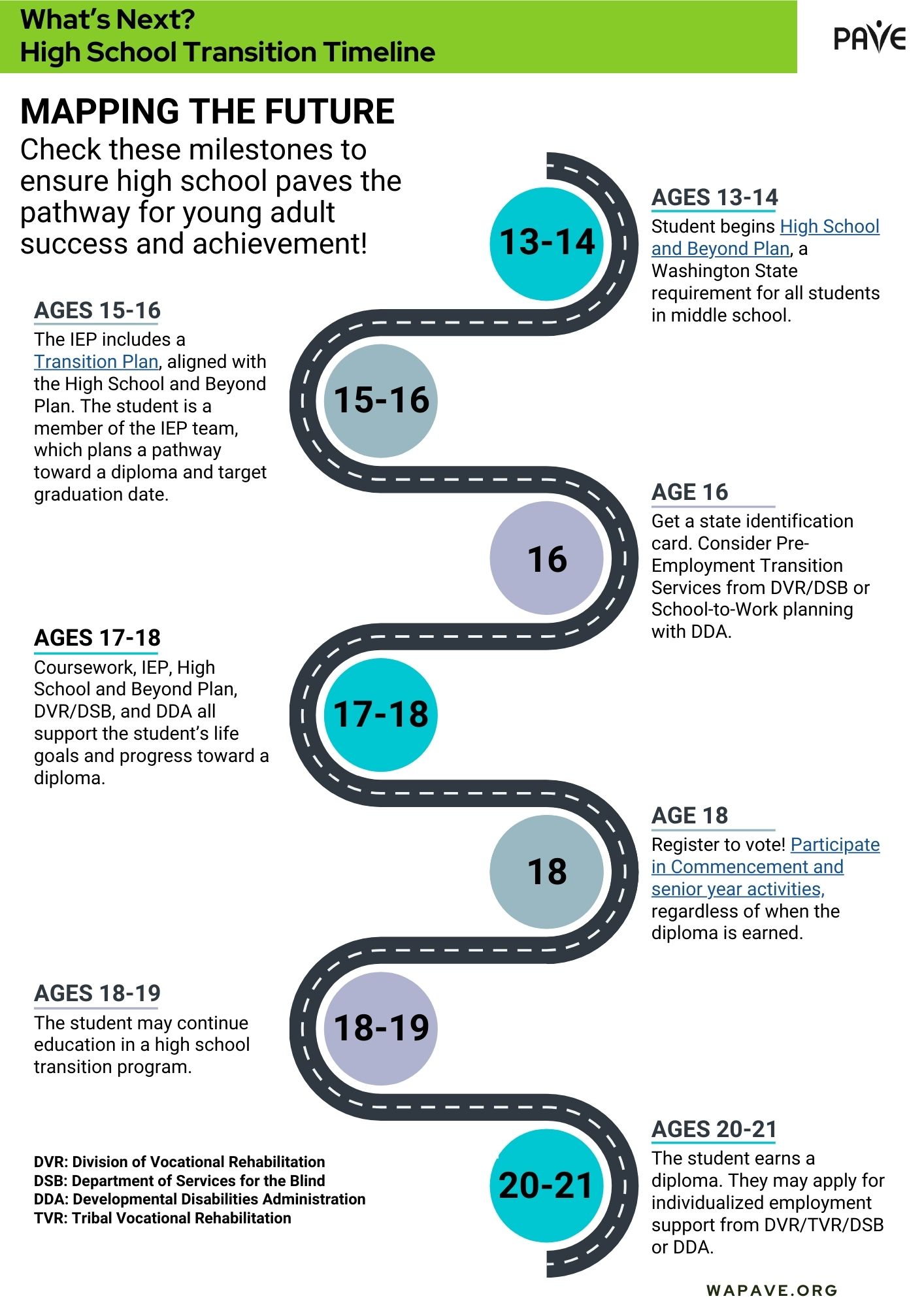

- By the time you are 16 years old, the school is required to invite you to your IEP meetings. You can attend any time, and leading your own meeting is a great way to learn important skills.

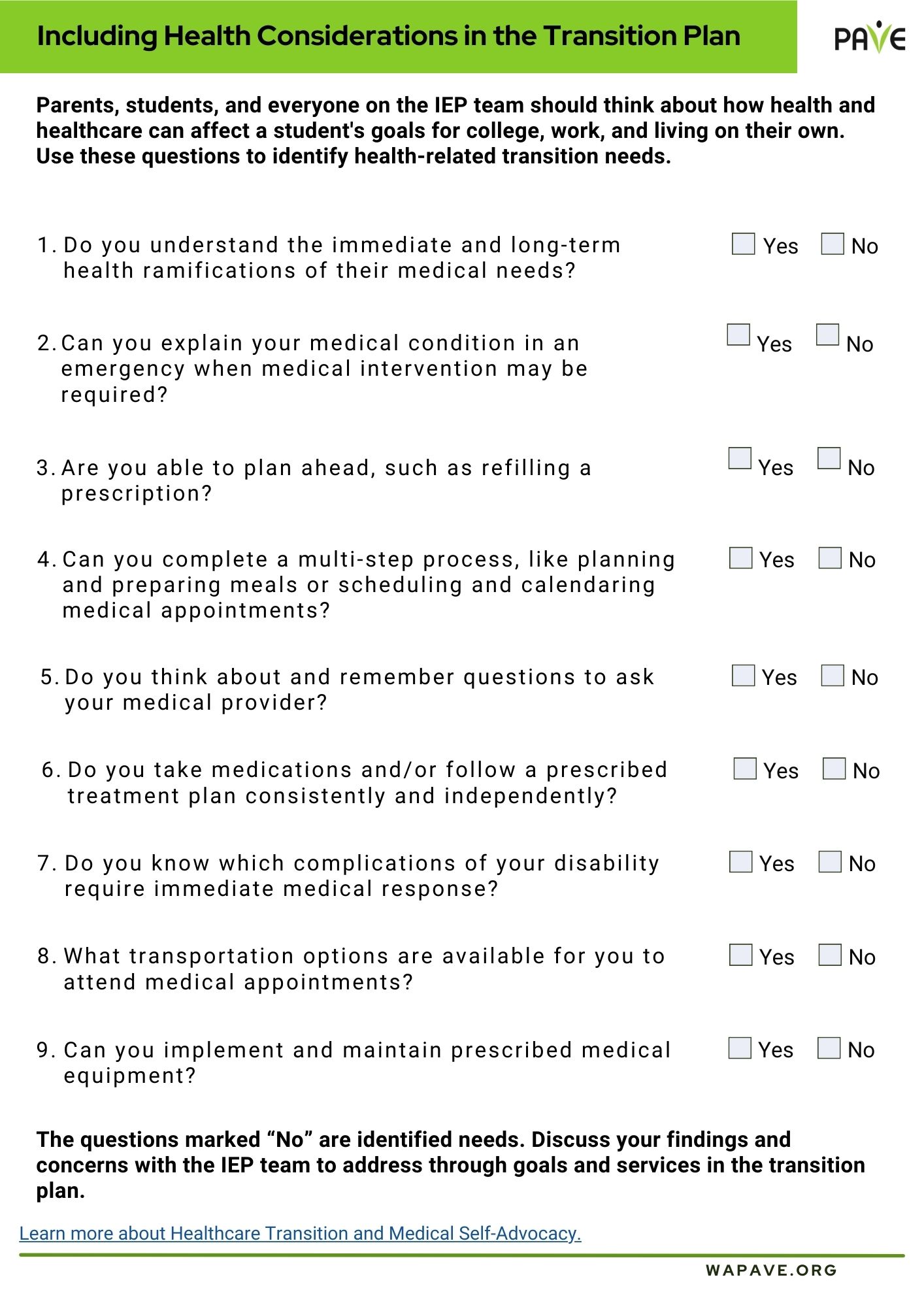

- The part of the IEP that focuses on your adult goals is called a Transition Plan, and it is all about you and your future.

- If you need more help at school or aren’t learning what you need to learn, then your IEP might need some fixing. Your voice matters on the IEP team.

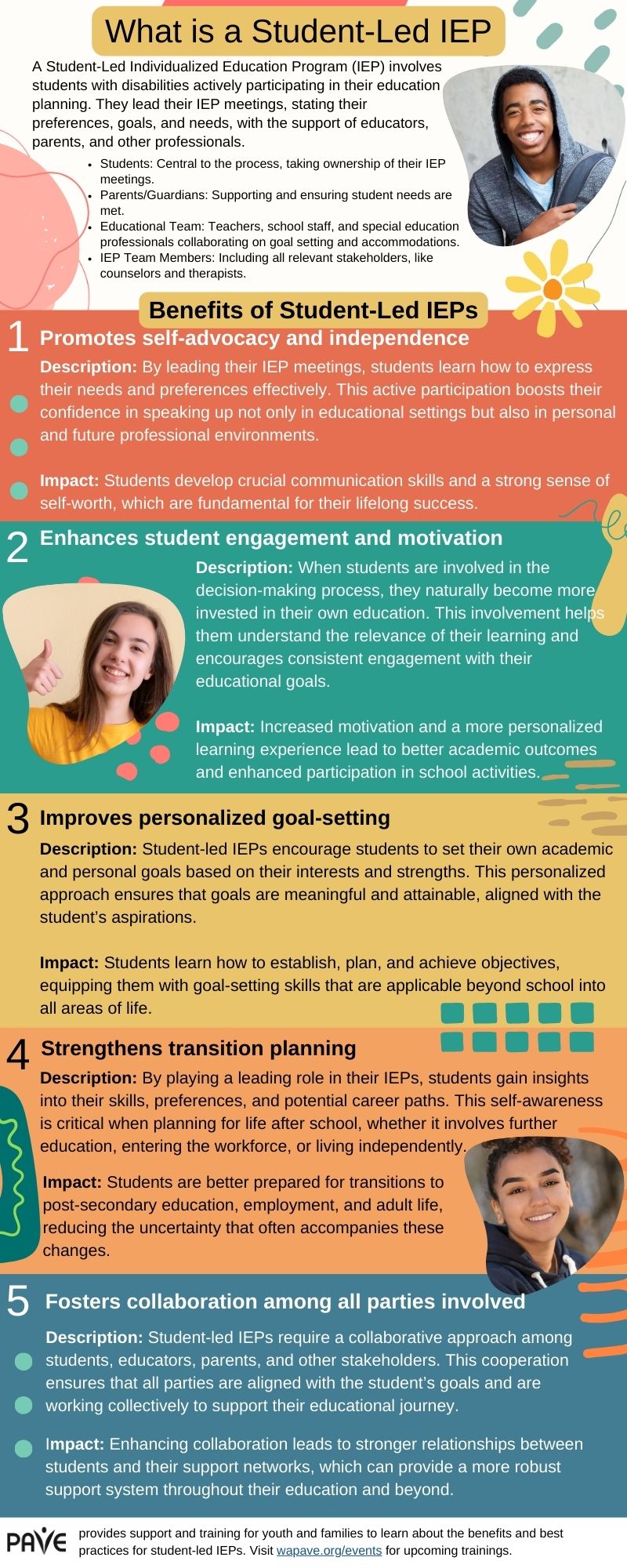

- PAVE provides an infographic overview of Student-Led IEPs, available for download in multiple languages at the bottom of this article..

Introduction

It’s important to plan your time carefully so that every school day gets you closer to where you want to be when you are an adult.

Learn to be a self-advocate

An advocate (pronounced ad-vo-cut) is someone who asks for something in a public way. Public schools get money from the government, so they are considered public entities. When you ask the school to provide you with something that you need to succeed, then you are being a self-advocate.

The word advocate can also be an action word (a verb), but then it’s pronounced ad-vo-cate (rhymes with “date”). You advocate for yourself when you ask for what you need to succeed.

Here’s another way to use this hyphenated word: You can say that you “practice self-advocacy.” Leading your own IEP meeting is a great way to practice self-advocacy and develop important adult skills.

Your Transition Plan focuses on where you want to go

The part of the IEP that focuses on your adult goals is called a Transition Plan. The Transition Plan is added to the IEP by the school year when you turn 16. The plan includes details about:

- when you plan to graduate (you can stay in school until your 22nd birthday if your IEP goals require more time)

- what jobs you might choose

- whether college is part of your plans

- what lifestyle you imagine for yourself (will you drive, cook, shop, live alone?)

- how school is getting you ready for all of that

The Transition Plan is all about you and your future. You can start taking charge of your future by going to your IEP meetings. You may want to lead all or part of the meeting, and you have that right.

By the time you are 16 years old, the school is required to invite you to your IEP meetings. From that year on, your school program is matched to your long-term goals.

The law says it’s all about you

Your rights as a student with an IEP are part of a federal law called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The IDEA says that schools must include family members and students on the IEP team. If you don’t play on the team, you can’t win the game, right? This is more important than a game—it’s Your Life!

The IDEA is a unique law because it says you get what you need in order to access school and learning. Getting an education that is specially designed just for you is called an entitlement. What you are entitled to is called FAPE, which means Free Appropriate Public Education.

You can become a leader on your IEP team by learning more about FAPE and how to talk about what it means to you. Public education is free for all school-age students in the United States, but consider this question: What makes your education appropriate?

Here are some questions to help you think and talk about FAPE:

- What is it like to have a disability?

- What about your disability makes school hard?

- What do you need at school that helps you learn?

- Are you getting better and better at the skills you need to be good at?

- Are your teachers helping you see what you do well?

If you are learning important skills at school, and your learning is helping you build on your strengths, then you are probably getting FAPE. If you need more help or aren’t learning the skills that you need to move forward, then your IEP might need some fixing. Keep in mind that the school is responsible to provide you with FAPE. You have the right to ask for FAPE.

Learn what your IEP can do for you

Here’s a starter kit to help you understand what your IEP says and how you can ask for changes. When you go to your IEP meeting, you have the right to ask the teachers and school administrators to help you read and understand your IEP.

These are some important parts of an IEP:

- Category of Disability: This is on the “cover page” of the IEP document. It lists the type of disability that best describes why you need individualized help at school. You should know this category so you can understand how and why teachers are supposed to help you.

- The Present Levels of Performance: This is the long section at the beginning of the IEP that describes how you are doing and what the school is helping you work on. The beginning of this section lists what you are good at. Make sure that section is complete so you can be sure the teachers help you build on your strengths.

- Goals: When you qualified for an IEP, the school did an evaluation. You showed that you needed to learn certain things with instructions designed just for you. To help you learn, the teachers provide Specially Designed Instruction. They keep track of your progress toward specific goals in each area of learning. You can learn what your goals are and help track your progress. The I’m Determined.org website provides videos of students describing their goals and other downloadable tools, like worksheets to help you track your goals.

- Accommodations: You can ask for what you need to help you learn in all the different classrooms and places where you spend the school day. Do you learn better if you sit in a specific part of the classroom, for example, or if you have a certain type of chair? Do you need to be able to take breaks? Do you do better on tests if you take them in a small, quiet space instead of the regular classroom? Do you need shorter assignments, so you don’t get overwhelmed? Helping your teachers know how to help you is part of your job as an IEP team member.

Get Ready for Your IEP Meeting

You can get ready for your IEP meeting by looking over the IEP document. You may want to ask a family member or a teacher to help you read through the document. If you don’t understand what’s in your IEP, plan to ask questions at the meeting.

PAVE provides a worksheet to help you prepare for your meeting. It’s called a Student Input Form. You can use this worksheet to make a handout for the meeting or just to start thinking about things you might want to say. If you don’t want to make a handout, you might draw pictures or make a video to share your ideas.

These sentence starters might help you begin:

- I enjoy…

- I learn best when…

- I’m good at…

- It’s hard for me when…

- I want more help in these areas…

- I like school the most when …

- Teachers are helpful when they…

- I want to learn more about …

- It would be great if…

You may want to think about your disability and how it affects your schoolwork. You could work on a sentence or draw a picture to help the teachers understand something that is hard for you. These might be the parts of a sentence that you can personalize:

- My disability in the area of …

- makes school difficult because…

Your handout can include a list of what you want to talk about at the meeting. Here are a few ideas, but your options are unlimited:

- A favorite class, teacher or subject in school?

- A time during the school day that is hard for you?

- Your IEP goals?

- Something that helps you feel comfortable and do well?

- Something you want to change in your school schedule or program?

- Graduation requirements and when you plan to graduate?

- Your High School and Beyond Plan?

- Anything else that’s important to you?

It’s never too soon to plan ahead!

Setting goals and making some plans now will help your school and family help you make sure you’ve got the right class credits, skills training and support to make that shift out of high school easier.

Being a leader at your IEP meeting is a great way to build skills for self-advocacy and self-determination, which is another great two-part word to learn. Self-determination means you make choices to take control of your life. At your IEP meeting, you can practice describing what helps you or what makes your life hard. You get to talk about what you do well and any projects or ideas that you get excited about. In short, you get to design your education so that it supports your plans to design your own adult life.

Learn More

- PAVE has prepared Planning My Path: A User-Friendly Toolkit for Young Adults, a collection of tips and tools to help students plan for their future.

- Seattle University’s Center for Change in Transition Services provides a toolkit for youth to plan for their futures and training information on writing transition plans, student-led IEPs, and job shadowing experiences.