Overview

- Physical Education (PE) can be adapted (changed) in four main ways to support students with disabilities.

- Federal and state law protects your rights to be taught PE. Adapted PE can be included in your Individualized Education Program (IEP). It can also be included in a Section 504 plan.

- Adapted PE can be useful for post-high school transition plans.

- Taking part in IEP and 504 meetings is important when looking at adapted physical education. It lets you share your needs, preferences, and goals. This helps create a physical education program that fits your abilities, supports your well-being, and creates a positive and inclusive environment. (Click on the links in the reference section to learn more about going to IEP and 504 meetings.)

- Changes in WA State rules mean that more teachers will qualify to design and teach Adapted Physical Education. These rules are in effect as of May 1, 2024.

- The Updated Guidance on Adapted Physical Education, from the Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) quoted in this article gives more information about Adaptive PE and how it fits into special education in WA State. Download or read Updated Guidance on Adapted Physical Education.

Full article

Why is physical education important? How is it helpful to me, as an individual with a disability?

Classes can teach you to care for your body and learn physical, mental, and emotional skills that include:

- Motor skills (training to use your muscles for certain things, such as swinging a baseball bat to hit a ball, or running very hard in a race)

- Physical fitness (keeping healthy and strong by exercising your body)

- Social-emotional skills, teamwork, social play skills

- Skills for athletics like team sports like soccer or basketball or individual athletics like gymnastics or dance

- Skills for recreation like biking, swimming, hiking, throwing frisbees, playing games with friends

How Adapted PE works:

Access or accessible means how easy it is to do, to get, or understand something.

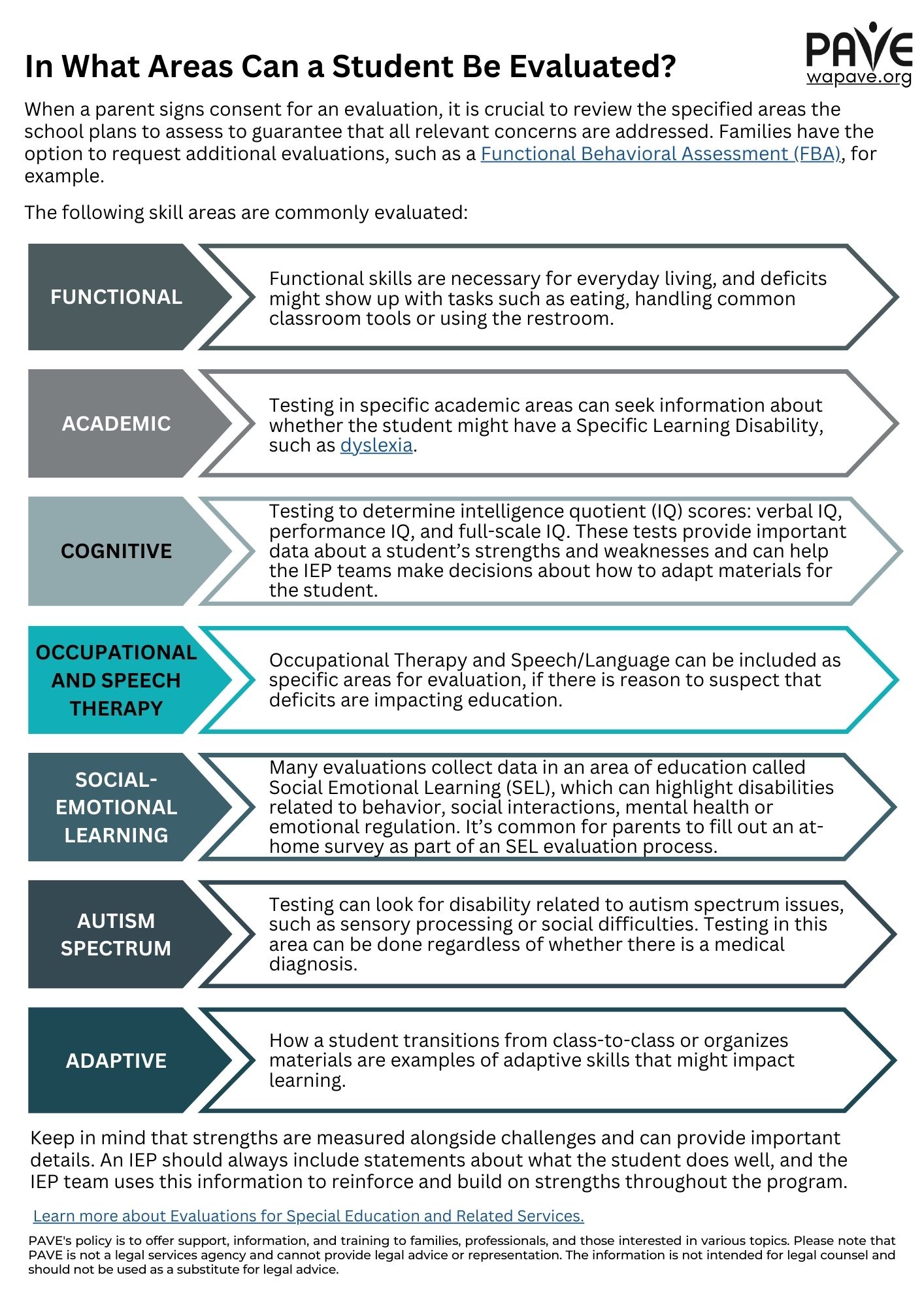

There are four main areas where changing general PE curriculum (school courses) may help you access PE. Some of these changes will benefit ALL students using the general PE curriculum.

- The physical space can be changed to work well for all students:

- The size of the space and the number of other students can affect how accessible the PE class is for you.

- Lighting, sound, and what you see can all affect your comfort in a class. Making thoughtful changes to these things can make a PE class more accessible.

- Teaching: the teacher gathers information about individual students to make sure that they use teaching methods that are accessible to everyone. This might mean spoken instructions, movements, pictures, written words, showing how to do something, or videos.

- Equipment: depending on your disability, you might need PE equipment to move more slowly, be bigger or smaller, easier to feel, be easier to see and other changes like those.

- Rules: to make sure PE includes everyone, rules of the game may need to be added or taken away.

Examples of Adapted PE

The point of Adapted PE is to change the general PE curriculum so that it is accessible for you or any other student with a disability. The changes can be individualized, which means it is designed for one individual student with disability. Changes will depend on what your needs are and will be different from student to student. Here are some examples:

- A third grader with autism spectrum disorder uses a play script on her communication device to invite other students to play tag with her.

- A high-school senior with Down Syndrome is introduced to adult recreation choices in his community so he can continue building healthy habits after graduation.

- A seventh grader with Cerebral Palsy attends general PE class. The Adapted PE teacher, general PE teacher, and the physical therapist work together to create an exercise plan to strengthen the student’s legs while using their walker.

- Design a unified team for sport activities and competitions, so a high school student with disabilities can play in the same team with students without disabilities

- Adapted Physical Education teachers are trained to make changes to the general education PE curriculum to make it accessible to students with disabilities.

IEPs can include Adapted PE as a service

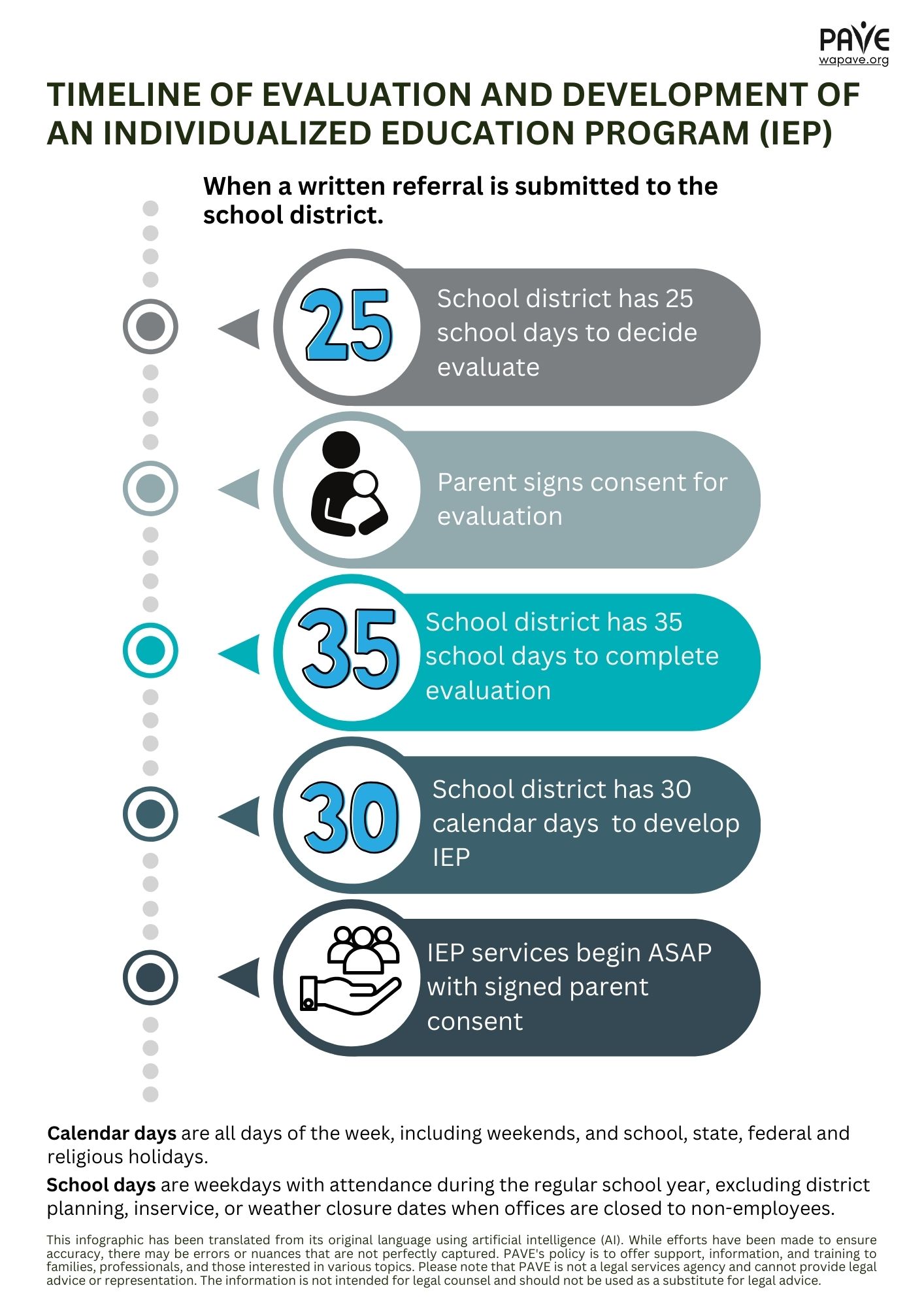

To get an Individualized Education Program (IEP) you need an evaluation. This process helps to decide if a student has a disability, if the disability has a significant impact on (really affects) learning, and if you need Specially Designed Instruction (SDI) and/or related services to access a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). FAPE is the right of any student, ages 3-21, who is eligible for school-based services delivered through an IEP.

If a student’s access to PE affects learning and needs the school’s PE course to be individualized, Adapted PE can be given as an IEP service. IEP teams discuss how Specially Designed Instruction (SDI) is delivered for each individual student.

If you have Adapted PE in your IEP, there is a range of options for placement. You might be in a general PE class, with or without accommodations. Additional aids, services, and modifications may be added depending on what you need. Get more details in the Updated Guidance on Adapted Physical Education.

You can go to IEP and 504 meetings to let the team know what you want and need. Beginning at age 14, you can participate in IEP and 504 meetings. You do not have to be invited by the school or your parents, but it’s a good idea to let your parents know you want to go, and to get ready before the meeting. When you are at these meetings, you can show other team members what is important to you about your learning, including Physical education. (Click on the links in the reference section to learn more about going to IEP and 504 meetings.)

All of you on the team can work out a PE plan, which may include Adapted PE, and put it in your IEP. There are two articles in the References section at the end about going to your IEP meeting.

Post-High School Transition and Adapted PE

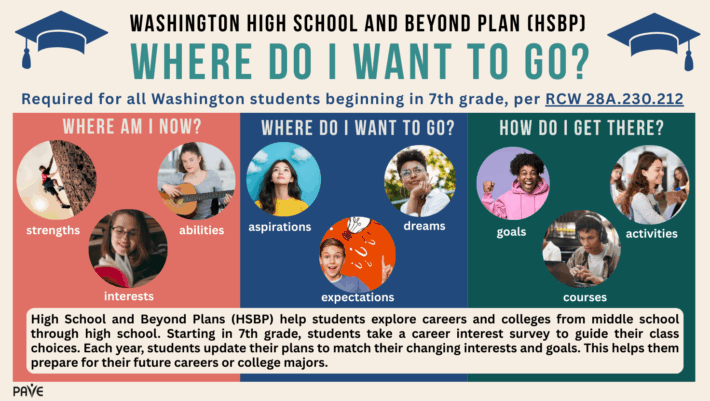

Physical education and/or Adapted PE can play a key role in your’ post-high school transition plans so you can be healthy and active in your adult life.

If you have Adapted PE in your IEP or 504 plan, you can work with your transition team to identify the sports and recreation activities, entertainments, and any after-school programs you enjoy or want to join. You can plan to continue favorite school PE activities out in the community and explore new options. The transition period is also an ideal time for you to create fitness plans or exercise routines to do independently. For this part of your transition planning, your PE/Adapted PE teacher can be invited to join the transition team, if they are not already a part of it.

Adapted PE teachers and physical and occupational therapists, if part of your IEP or 504 team, can work together on skills related to physical activities and recreation. Some examples might include using a locker room, showing ID or membership at a reception desk, registering for programs or classes, and care and proper use of your sports equipment at home.

Rules changed and removed some difficulties with getting Adapted PE

Until spring of 2024, Adapted PE was not accepted as a specialty that the state would endorse (add to the training listed on a teacher’s professional certificate). This caused a shortage of teachers who could design Adapted PE for students. It made it difficult for some students with disability in Washington State to get SDI in physical education.

As of May 1, 2024, qualifying[1] teachers in Washington State can be trained for and receive a specialty endorsement in Adapted Physical Education. The endorsement shows the teacher has specific skills and knowledge in both PE Learning Standards and special education competencies. As more teachers are taught this specialty, it will be easier to find teachers with Adapted PE training in Washington State.

The OSPI Updated Guidance says that in addition to teachers with an Adapted PE endorsement, SDI for physical education can be provided by “any other appropriately qualified special education endorsed teacher, or an “appropriately qualified Educational Staff Associate (ESA) such as an Occupational Therapist (OT) or a Physical Therapist (PT).”

Summary:

- Physical Education (PE) is an important part of school. Students with disabilities have the right to be taught physical education.

- Adapted PE is when the general PE school course (curriculum) is changed to accommodate (meet the needs) of an individual student with disability.

- Adapted PE can be included in an Individualized Education Plan or a Section 504 plan.

- If a student needs Adapted PE, it’s important to include someone on the IEP team who is qualified to design adapted PE, as well as the teacher or other school staff who will be teaching the student.

- Only certain qualified education professionals can design and supervise other educators and school staff teaching Adapted PE. Changes in WA State rules in 2024 allow more education professionals to qualify in Adapted PE.

Resources:

Updated Guidance on Adapted Physical Education (WA State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI))

Attention Students: Lead your own IEP meetings and take charge of your future (PAVE)

Students: Get Ready to Participate in Your IEP Meeting with a Handout for the Team (PAVE)

Who’s Who on the IEP Team (PAVE)

Student Rights, IEP, Section 504 and More (PAVE)

A previous version of this article was based on information provided by two experts in the field of Adapted Physical Education, Toni Bader, and Lauren Wood, who are Adapted Physical Education teachers in the Seattle area:

Toni Bader, M.Ed., CAPE – SHAPE Washington, Adapted Physical Education, Seattle Public Schools (tonibader24@hotmail.com)

Lauren Wood, NBCT, Adapted Physical Education Teacher, Highline Public Schools, and SHAPE Washington Board Member (lauren.wood@highlineschools.org)

[1] “Certificated teachers who hold any special education endorsement or a Health/Fitness endorsement are eligible to add the APE specialty endorsement to their certificate” –OSPI Updated Guidance