A Brief Overview

- Keeping track of important documents for your child’s health can save you time and give you less stress.

- Take advantage of technology! If you choose to build a digital storage system, integrating it with your smart phone will make it easy to share information on-the-go with doctors, day care providers, school staff, and other professionals.

- Plan a grab-and-go handout, notebook, or phone app to make it easy to find and share critical information during an emergency.

- Read on for information about how to get started!

Full Article

Care planning and a well-organized system to keep track of important documents can save time and create comfort during uncertain times. This article provides some tips for building a “care notebook,” which might be a three-ring binder, an accordion file, or a portable file box—whatever makes sense for your organizational style and the types of materials you need to sort.

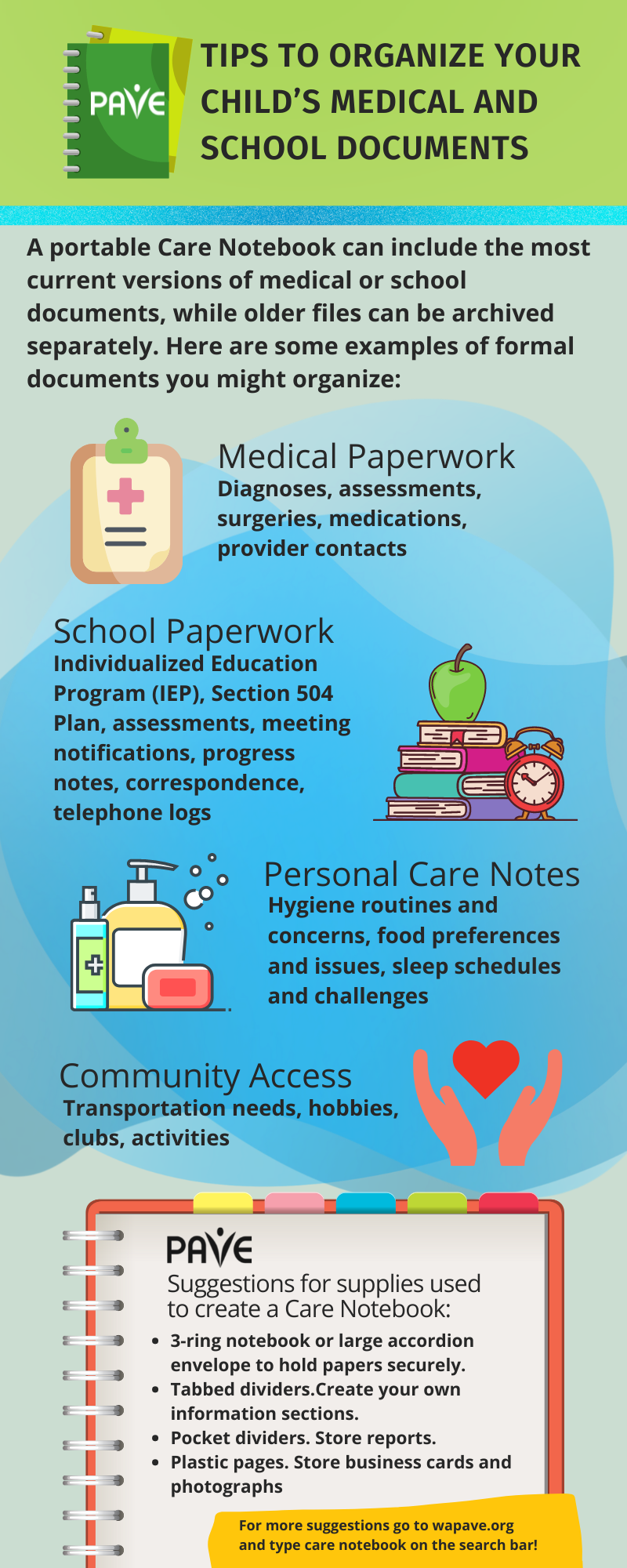

A portable Care Notebook can include the most current versions of medical and/or school documents, while older files can be archived separately. Here are some examples of formal documents you might organize:

- Medical paperwork: diagnoses, assessments, surgeries, medications, provider contacts

- School paperwork: Individualized Education Program (IEP), Section 504 Plan, assessments, meeting notifications, progress notes, correspondence, telephone logs

- Personal care notes: hygiene routines and concerns, food preferences and issues, sleep schedules and challenges

- Community access: transportation needs, hobbies, clubs, activities

Click to print out the infographic above

Consider what else to include, such as business cards and contacts, a call log, a calendar, emergency/crisis instructions, prescription information, history, school schedule…

Each primary category can be a section of a large notebook or its own notebook. Consider how portable the notebook needs to be and where you might take it or share it. Will the size and shape be practical for where you plan to go? Do you need more than one notebook or system?

One way to make the most current medical information more mobile is to use an app on your phone or tablet. Here are two options:

- Specifically for an iPad or iPhone and available through Apple, My Health Tracker was developed through Boston Children’s Hospital and Boston University.

- Available for android phones through Google Play, MyCookChildren’s provides categories and ways to take pictures of documents and/or store information that you enter.

Both mobile apps help you track medication, care needs, illnesses, and appointments. Having this information in one place is especially helpful when you are working with specialists and medical providers from different medical groups that use different calendar and records systems.

Another way to maintain records and information is to create a digital “notebook” on a personal computer. You might build folders just like you would in a physical notebook. Dr. Hempel Digital Network provides 10 health-record applications with options that combine electronic medical records with telehealth capabilities. Other applications work with cellular phones. Here are three: MTBC PHR, Medical Records, and Medfusion Plus.

Keep emergency information handy and easy to clean

A small “on the go” handout might be helpful for critical care appointments or emergencies. A laminated handout or a page tucked into a protective sleeve will be easier than a large notebook to disinfect after being in public. Depending on a child’s needs, caregivers might create multiple copies or versions of an on-the-go handout for easy sharing with daycare providers, school staff, babysitters, the emergency room, camp counselors or others who support children.

Key information for a quick look could include:

- medications and dosages

- doctors and contact information

- emergency contacts—and whom to call first

- allergy information

- preferred calming measures

- Plan for a caregiver’s illness

Another pull-out page or small notebook might include specific instructions about what to do if a caregiver gets sick. These questions could be addressed:

- Who is the next designated caregiver?

- Where can the child live?

- What are specific daily care needs and medical care plans?

- Is there a guardianship or a medical power of attorney?

- Are there any financial or long-term plans that need sharing?

Step-by-Step Instructions

Building a Care Notebook does not have to be daunting. Most people start small and try different approaches until they find the best fit. Here are a few ideas to start the process:

- Choose a holding system that makes sense for your organizational style: notebook, accordion file, small file box, or a primarily digital system with limited “to-go” handouts.

- Identify and label the document sections by choosing tools that fit your system: dividers, clear plastic document protectors, written or picture tabs, color coding, card holders for professional contacts, a hierarchy of folders on your computer…

- Include an easy-to-access calendar section for tracking appointments.

- Include a call log, where names are recorded (take time to spell full names correctly!) and phone numbers of professionals. Take notes to create a written record of a conversation. It is also practical to send a “reflective email” to clarify information shared in a call, then print the email, and tape it into the call log to create a more formal written record of the call.

- A separate sheet of easy-reference information can be used to share with a caregiver in a new situation, such as daycare, doctor, camp, or a sleepover. Mommies of Miracles has an All About Me template that serves this purpose.

- When appropriate, invite the child to participate.

Tools to help you begin

Quick and easy forms can help you start. Here are two options:

- Medical Home Portal Care Notebook and it comes in both English and Spanish

- Individual Healthcare and Emergency plans from PACER Center

Guidance to help build a more comprehensive care notebook is available from Family Voices of Washington. Printable forms can be done in stages and updated as needed to slide into a notebook or filing system. The templates include pull-out pages for Emergency Room or Urgent Care visits and forms to help organize medical appointments.

A child’s medical providers might help write a care plan and can provide specific contact information, medication lists and emergency contact procedures for each office. A school can provide copies of an Individualized Education Program (IEP), a Section 504 Plan, an Emergency Response Protocol, a Behavior Intervention Plan or other documents. If a child is in state-supported daycare (on location or in-home), staff can provide forms for emergency procedures and contacts.

You will thank yourself in the future!

Having information organized and ready can make it easier to apply for public services through the Social Security Administration, the Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA), the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) or others. For military families, a Care Notebook can make transitions and frequent moves easier to manage.

A well-established organization system also can help a child transition toward adult life. Easy access to a list of accommodations can ease that first meeting with a college special services office or provide a key set of documents for requesting vocational rehabilitation/employment supports. Easy access to key medical records can be the first step to helping a child learn what medications they are taking and advocate for an adjustment with an adult provider

Additional resources for long-term planning include:

- The Family Handbook of Future Planning from The Arc of the United States

- Possibilities from the PACER Center