A Brief Overview

- Person-Centered Planning (PCP) is a method for helping a person map out a future with intention and support.

- Read on for more information about what Person-Centered Planning is like.

Full Article

Everyone dreams about what they might do or become. Individuals with disabilities might need additional support to design the plans, set the goals and recruit help. The Person-Centered Planning (PCP) process is a tool that works like a Global Positioning System (GPS) to help a person figure out where they are starting and how to navigate to a planned destination.

A PCP session is a gathering that can happen in a specific physical location, such as a school or a community center, or in a virtual space online. The people who get together might include family members, friends, teachers, vocational specialists, coaches—anyone who might help brainstorm ways to plan an enriched, full life for a person of honor.

The first step is to celebrate the gifts, talents, and dreams of the person. Then the group develops action steps to help that person move closer to their dreams and goals.

Throughout the gathering, the attendees listen, ask questions, and draw pictures or write down words that contribute to the process. Respect for the person’s goals and wishes is a priority, and participants withhold judgment to honor the individual completely.

Person-Centered Planning explores all areas of a person’s life. All people experience various times in their lives that are transitions. High-school graduation is a major example. Job changes, moving to a new home, entering or leaving a relationship: Those transitions happen for individuals with and without disabilities.

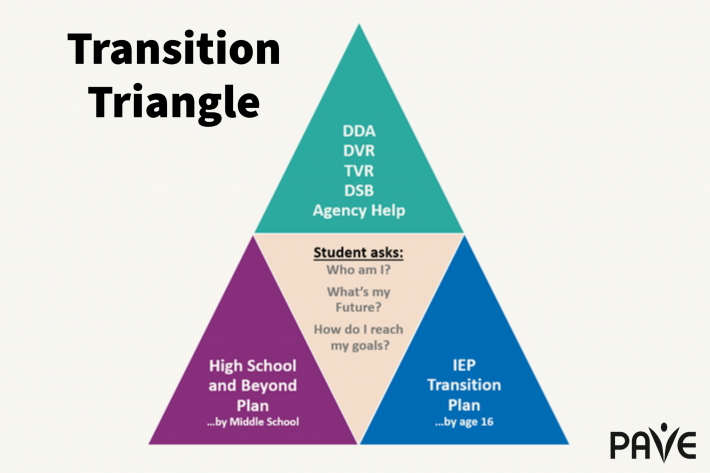

Individuals with disabilities have some additional transitions. For example, when a person leaves the special education system of public education at graduation or after age 21, there is a change in disability protections. A student receiving special education is protected by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). In adult life, the right to accommodations and non-discrimination is protected solely by the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

There are specific transitions that occur for individuals who qualify for support from the Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA), which in Washington is part of the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS). Employment and workforce training programs often are part of the transition from high school into what happens next.

During major life transitions, many service agencies focus on a person’s inabilities or deficits. Person-Centered Planning, on the other hand, focuses on what’s positive and possible, based on the dreams and goals of the individual.

A PCP session includes a set of maps where information is collected in words and pictures. Here are some examples:

People in my Life

This map names important people and their roles in concentric circles. These are people that the individual trusts for help and support and may include paid and unpaid supporters. Those who are closest to the person are in the circles closest to the center of the map.

Who am I? My Story, My History

This map is built during the session to describe the person’s story from birth up until the gathering. This map reflects what is most important to the individual. The facilitator might ask:

- What parts of your life are important for people to know?

- What are some stories of your life that would be helpful for a coworker or a friend to know?

- Are you a sibling? A spouse? A parent?

- How old are you?

- What activities do you participate in?

- Have you had any jobs?

- Where do you live? Go to school?

- Do you have a medical concern that someone spending time with you might need to know about?

Likes and Dislikes

The “Likes” list includes favorites, things that make the person happy. Favorite colors, foods, activities, places, people are listed.

The “Dislikes” list includes the opposite of all those things and might also list triggers (bright lights, loud noises, angry voices, bullies) or other sensitivities.

What Works/ Doesn’t work

The first part of this map asks: When learning a new activity or skill, what are steps and learning tools or activities that work for you? Answers might look like these examples: frequent breaks, accommodations, a written schedule, a list of duties, instructions in larger print, a preferred time of day to start something….

The second part asks: When learning a new activity or skill what activities do not work for you? Answers might resemble these examples: waiting in line, too many instructions, too many people barking out orders, standing or sitting for too long, verbal instructions, unclear expectations….

Gifts, Talents and Strengths

This map asks several questions:

- What are you good at?

- What can you do that is easy for you?

- What are your best qualities?

- What do people like about you?

Examples for answers: best smile, cleaning, giving, caring, natural dancer, very social, great with computers, good with numbers, great at sports, good listener, good with animals, etc.

Dreams /Nightmares

The My Dreams map asks: Where you would like to see yourself in a few years? Follow-up questions:

- What will you be doing?

- What would your dream job be?

- Where are you living?

- Do you live on your own or with family or a roommate?

- How are you keeping in touch with your friends?

- What is an action you can take to move toward your dream or goals?

The Nightmare Map asks: What do you want to avoid? Follow-up questions might include this one: Where do you not want to be in a few years? This is not to make the person feel bad but to make an out-loud statement about what the person doesn’t want to happen. This can include actions or thoughts that someone wants to avoid.

Needs

The Needs map asks: What do you need help with to avoid the nightmare? A follow up question might include: What areas do you need support with? Answers might look like these examples: budgeting money, learning to drive, training to ride the bus, cooking lessons, looking for a job. The goal is to recruit support to help the person stay away from the nightmare and work toward the dream.

Action Steps

A map that show Action Steps includes the specific help that will assist the individual in moving toward the dream. This chart typically details what needs to be done, who will do it, and by when.

Example:

Goal: To Write a Resume

Who: Michele

What: Call Mark to ask for help.

By When: Next Monday, April 6, 2020

This process involves many support people in the person’s life and identifies, in a self-directed way, areas where help is needed to meet personal goals. The gathering involves the important people in someone’s life because they can help through the process and step up to offer support for the action steps.

How to get a Person-Centered Plan

Here are places that might help you find a PCP facilitator in your area:

- Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA)

- Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR)

- School District

Here are a few additional places to seek information about Person-Centered Planning:

Inclusion.com: All My Life’s a Circle

Inclusion.com: The Path Method

Video from PAVE, Tools 4 Success

Informing Families.org