June 19 @ 12:00 pm – 2:00 pm PDT

In need of support, training and resources for your child’s IEP/504? Sherry Mashburn with PAVE is here to help.

pti@wapave.org

In need of support, training and resources for your child’s IEP/504? Sherry Mashburn with PAVE is here to help.

pti@wapave.org

Families United for A Better Future

Familias Unidas Para Un Mejor Futuro

05/31/2025

No Childcare Provided

Doors open at 7:30am

No Habrá Cuidado de Niños

Las puertas abren a las 7:30 am

7:30-8:00am- Registration/Registro

8:00-9:00am-Welcome & Keynote/Bienvenido y Keynote

9:15am-First Session will begin/ La priemera sesión comienza

“The Families Unite for a Better Future Conference is a bilingual (English and Spanish) event created for families and others caring for children—including those with developmental and other disabilities. This engaging, community-centered conference brings together parents, caregivers, educators, and professionals to explore practical strategies, share experiences, and strengthen support systems for children and youth.”

“La Conferencia Familias Unidas por un Futuro Mejor es un evento bilingüe (inglés y español) creado para las familias y otras personas que cuidan a niños y niñas—including aquellos con discapacidades del desarrollo u otras discapacidades. Esta conferencia, atractiva y centrada en la comunidad, reúne a padres, cuidadores, educadores y profesionales para explorar estrategias prácticas, compartir experiencias y fortalecer los sistemas de apoyo para la infancia y la juventud.”

• Limited Interpretation/Interpretación limitada

pti@wapave.org

Caring for individuals with disabilities or complex medical needs can be emotionally and physically draining, making intentional self-care essential for long-term well-being. Simple practices like mindfulness, getting enough sleep, going for a walk, or taking a few deep breaths can help reduce stress and build resilience. Talking to others who understand and finding time to rest can also help caregivers stay strong and healthy.

A Brief Overview

Raising children requires patience, creativity, problem-solving skills and infinite energy. Think about that last word—energy. A car doesn’t keep going if it runs out of gas, right? The same is true for parents and other caregivers. If we don’t refill our tanks regularly we cannot keep going. We humans refuel with self-care, which is a broad term to describe any activity or strategy that gives us a boost.

Self-care is not selfish! Without ways to refresh, we cannot maintain our jobs, manage our homes, or take care of people who need us to keep showing up. Because the demands of caring for someone with a disability or complex medical condition can require even more energy, refueling through self-care is especially critical for caregivers.

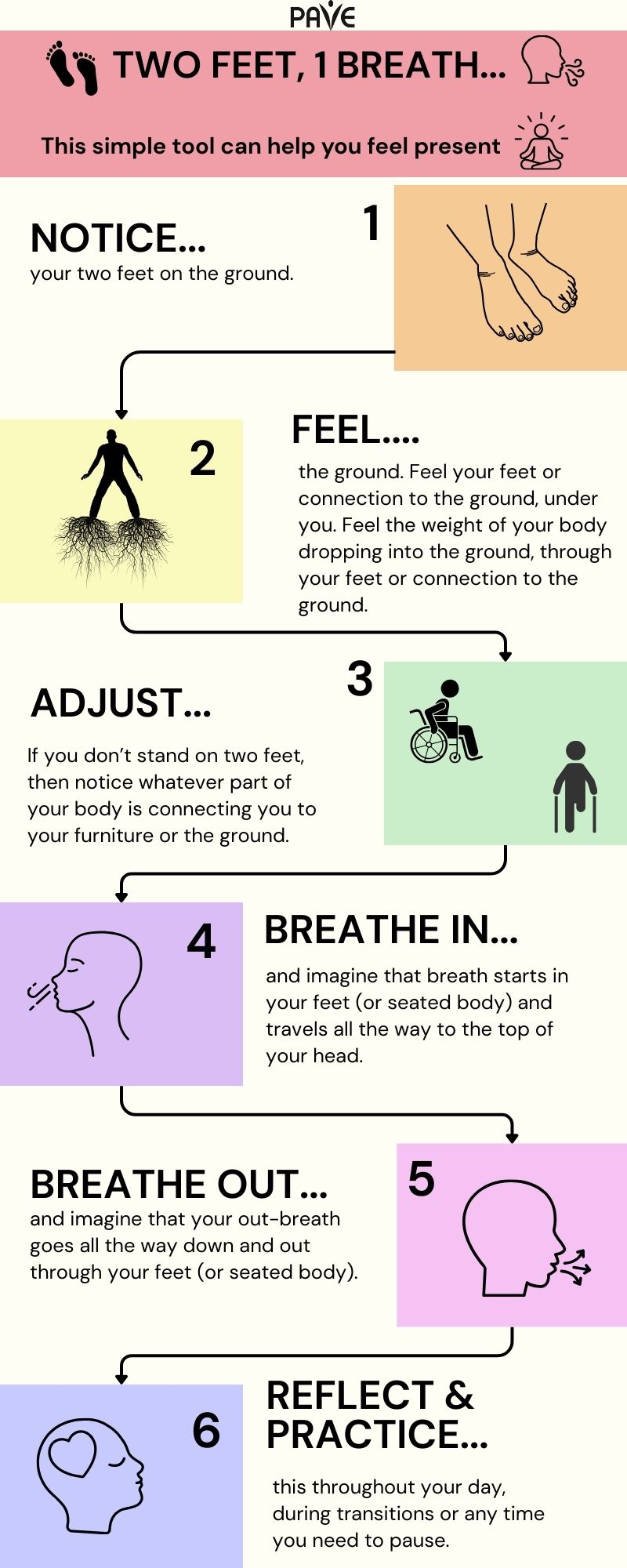

Before you read anymore, try this simple self-care tool called Two Feet, One Breath. Doctors use this one in between seeing patients.

Download this infographic, Two Feet 1 Breath:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Two Feet, One Breath can become part of every transition in your day: when you get out of bed or the car, before you start a task, after you finish something, or any time you go into a different space or prepare to talk with someone. This simple practice highlights how self-care can become integrated into your day.

Although a day at the spa might be an excellent idea, self-care doesn’t have to be fancy or expensive to have a big impact!

Almost everyone knows or cares for someone with special needs. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), at least 28% of the American population experiences a disability. The result is widespread compassion fatigue, which is a way to talk about burnout from giving more than you get.

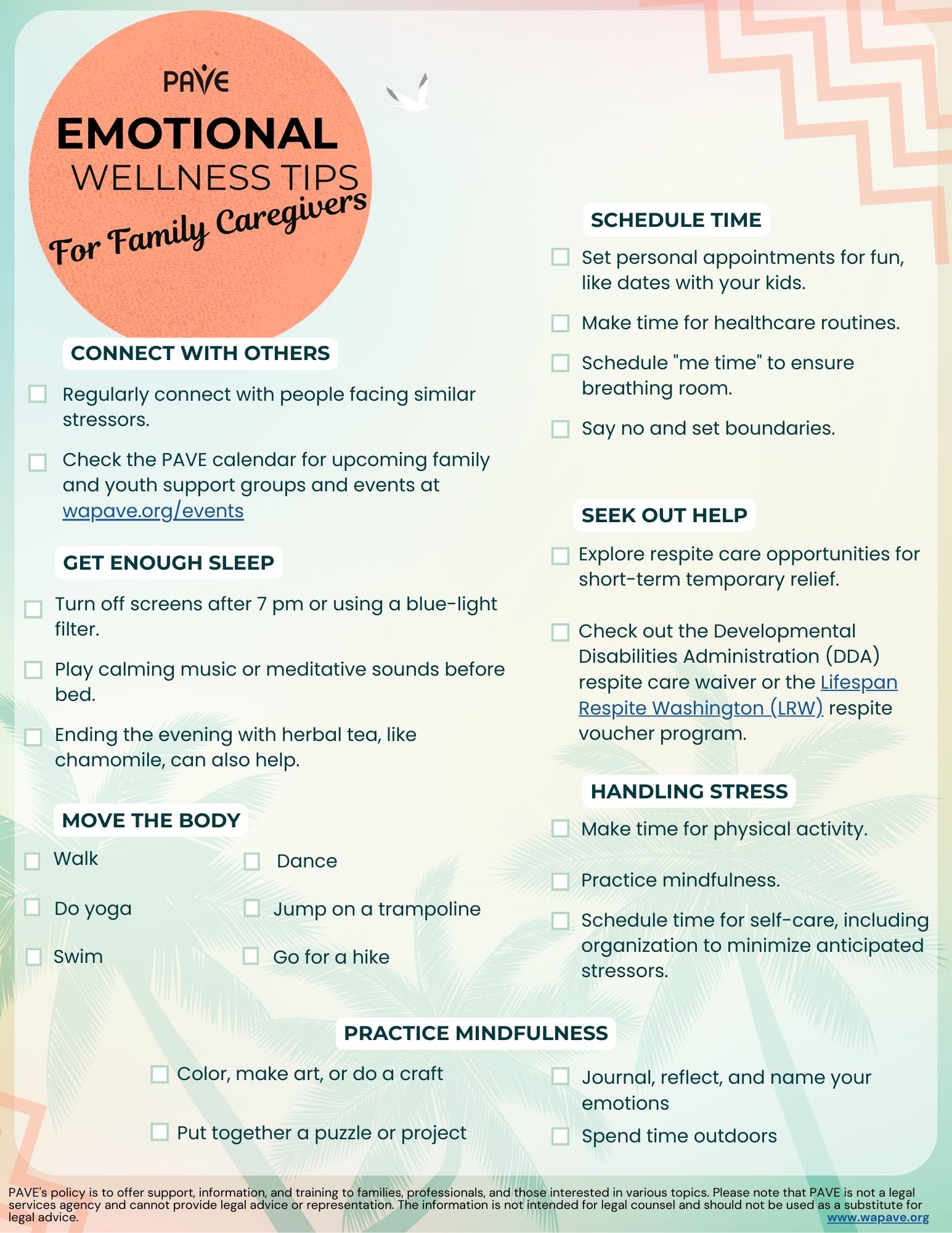

Below are some ways to use self-care to avoid burnout!

Building a support network with others who share similar life experiences can be incredibly valuable. When you’re going through a challenging or unique situation—like parenting a child with special needs or managing a family health issue—it can feel isolating. These connections offer emotional validation and a sense of understanding that can be hard to find elsewhere—you don’t have to explain everything because others simply get it. Research shows that social support can significantly reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, enhancing overall well-being and resilience. Beyond emotional comfort, support networks empower individuals by helping them build confidence, understand their rights, and even engage in advocacy efforts that benefit their families and communities.

Here are some communities and resources to help you get connected:

Parent-to-Parent Connections

The Parent-to-Parent network can help by matching parents with similar interests or by providing regular events and group meetings.

Support for Families of Youth Who Are Blind or Low Vision

Washington State Department of Services for the Blind (DSB) offers resources and support for families. You can also hear directly from youth about their experiences in the PAVE story: My story: The Benefits of Working with Agencies like the Washington State Department of Services for the Blind.

Support for Families of Youth Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing

Washington Hands and Voices offers opportunities for caregivers of youth who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHH) to connect, share experiences, and find community.

Resources for Families Navigating Behavioral Health Challenges

Several family-serving organizations provide support, education, and advocacy for caregivers of children and youth with behavioral health conditions:

PAVE provides a comprehensive toolkit for families navigating behavioral health systems, including guidance on crisis response, medical care, education, and family support networks.

The body uses sleep to recover, heal, and process stress. If anxiety or intrusive thinking consistently interrupts sleep, self-care starts with some sleeping preparations:

Moving releases feel-good chemicals into the body, improves mood, and reduces the body’s stress response. Walk or hike, practice yoga, swim, wrestle with the kids, chop wood, work in the yard, or start a spontaneous living-room dance party.

The Mayo Clinic has this to say about exercise:

Mindfulness can be as simple as the Two Feet, One Breath practice described at the top of this article. Mindfulness means paying attention or putting your full attention into something. Focusing the mind can be fun and simple and doesn’t have to be quiet, but it should be something that you find at least somewhat enjoyable that requires some concentration. Some possibilities are working on artwork, cleaning the house or car, crafting, working on a puzzle, cooking or baking, taking a nature walk, or building something.

For more mindfulness ideas, check out PAVE’s Mindfulness Video Series. From this playlist, Get Calm by Getting Organized, explores how getting organized provides satisfaction that releases happiness chemicals and hormones.

A day can disappear into unscheduled chaos without some intentional planning. A carefully organized calendar, with realistic boundaries, can help make sure there’s breathing room.

Set personal appointments on the calendar for fun activities, dates with kids, healthcare routines, and personal “me time.” If the calendar is full, be courageous about saying no and setting boundaries. If someone needs your help, find a day and time where you might be able to say yes without compromising your self-care. Remember that self-care is how you refuel; schedule it so you won’t run out of gas!

Time management is a key part of stress management! This article, “Stress Management: Managing Your Time” from Kaiser Permanente, gives tips for managing your time well, so you can reduce the pressure of last-minute tasks and make space for the things that matter most to you.

Respite care provides temporary relief for a primary caregiver. In Washington State, a resource to find respite providers is Lifespan Respite. PAVE provides an article with more information: Respite Offers a Break for Caregivers and Those They Support.

Parents and caregivers of children with developmental disabilities can seek in-home personal care services and request a waiver for respite care from the Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA). PAVE provides two training videos about eligibility and assessments for DDA. For more information about the application process, Informing Families provides a detailed article and video.

Download this checklist of Emotional Wellness Tips for Caregivers in:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Coffee & Tea with P2P – This drop-in support group is for parents and caregivers seeking support to navigate the various emotions and life adjustments of raising a child, youth, and adult with a disability. This parent group helps connect families to Pierce County community resources, fosters relationships with other parents, and builds a support network for parents feeling isolated. This group meets in-person monthly on the 1st Friday from 10-11am PT.

Highlights:

P2P@wapave.org

Coffee & Tea with P2P – This drop-in support group is for parents and caregivers seeking support to navigate the various emotions and life adjustments of raising a child, youth, and adult with a disability. This parent group helps connect families to Pierce County community resources, fosters relationships with other parents, and builds a support network for parents feeling isolated. This group meets in-person monthly on the 1st Friday from 10-11am PT.

Highlights:

P2P@wapave.org

Awesome Autism Parent Support Group – The Awesome Autism Parent Support Group is a community dedicated to providing a nurturing and empowering environment for parents and caregivers of children with autism. The primary goal is to offer emotional support, share resources, exchange experiences, and promote a sense of unity among parents, individuals, and families raising and child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The group meets online on the 2nd Thursday of the month from 12-1 pm PT.

Highlights:

Registration is required to get access to the Zoom link.

P2P@wapave.org

What Will I Learn?

Pierce County Parent to Parent partners with The ARC of Washington and Pierce County community connections to provide support, information, and education for parents of children with disabilities and special healthcare needs.

This is the required training to become a 1:1 helping parent volunteer and support other parents who have just learned their child has a condition or need support for any reason.

Helping Parent Volunteers and staff assist families in coping with many challenging experiences and feelings.

P2P@wapave.org

Provides a safe, validating, and empowering space for parents, caregivers, and families of African descent so they can find understanding, strength, and resources to navigate their unique and often challenging and isolating journey of raising Black/African American children or family member with a disability.

This group supports:

Open discussions,

Shared experiences and cultural and language sensitivity.

Meets virtually on the 2nd and 4th Tuesday of the month.

P2P@wapave.org

Coffee & Tea with P2P – This support group is for parents and caregivers seeking support to navigate the various emotions and life adjustments of raising a child, youth, and adult with a disability. This parent group helps connect families to Pierce County community resources, fosters relationships with other parents, and builds a support network for parents feeling isolated. This group meets in-person monthly on the 1st Friday from 10-11am PT.

Highlights:

P2P@wapave.org

This group meets virtually on the 1st Saturday of the month and Quarterly in person! Register to join us!

PAVES Pierce “Parent 2 Parent Support Groups” offers a nurturing space for caregivers to connect, share experiences, and find guidance. Parents come together to discuss challenges, celebrate successes, and exchange practical strategies in raising children with disabilities. Through mutual understanding and empathy, this group provides emotional support, valuable resources, and a sense of community, helping families navigate the unique journey of caring for their exceptional children with care and strength.

The P2P Caregiver Connection is dedicated for childcare providers, teachers, paraeducators/caregivers who support young children with disabilities and their families.

Please note that all parent support groups supply the following:

*Additionally, support groups specific to a cultural and linguistic community (Native, Spanish-speaking, and Black & African American families) will be supported by a PAVE facilitator that is a cultural/linguistic match for the families served.

This group meets virtually on the 1st Saturday of the month and Quarterly in person! Register to join us!

P2P@wapave.org

PAVES Pierce “Parent 2 Parent Support Groups” offers a nurturing space for caregivers to connect, share experiences, and find guidance. Parents come together to discuss challenges, celebrate successes, and exchange practical strategies in raising children with disabilities. Through mutual understanding and empathy, this group provides emotional support, valuable resources, and a sense of community, helping families navigate the unique journey of caring for their exceptional children with care and strength.

The P2P Caregiver Connection is dedicated for childcare providers, teachers, paraeducators/caregivers who support young children with disabilities and their families.

Please note that all parent support groups supply the following:

*Additionally, support groups specific to a cultural and linguistic community (Native, Spanish-speaking, and Black & African American families) will be supported by a PAVE facilitator that is a cultural/linguistic match for the families served.

P2P@wapave.org

New parents often worry about their child’s growth and development, especially when comparing with other children. Early intervention can be crucial for children with developmental delays or disabilities. In Washington, families can connect with a Family Resource Coordinator (FRC) for guidance and access free developmental screenings. The Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) offers services through Early Support for Infants and Toddlers (ESIT), providing evaluations and individualized plans (IFSP) to support eligible children from birth to age three. These services, protected under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), are typically free and aim to help children thrive in various settings.

New parents may struggle to know whether their child’s growth and development are on track. They may have a feeling that a milestone is missed, or they may observe siblings or other children learning and developing differently. Sometimes a parent just needs reassurance. Other times, a child has a developmental delay or a disability. In those cases, early interventions can be critical to a child’s lifelong learning.

Washington families concerned about a young child’s development can call the Family Health Hotline at 1-800-322-2588 (TTY 1.800.833.6384) to connect with a Family Resource Coordinator (FRC). Support is provided in English, Spanish and other languages. Families can access developmental screening online for free at HelpMeGrow Washington.

Several state agencies collaborated to publish Early Learning and Development Guidelines. The booklet includes information about what children can do and learn at different stages of development, focused on birth through third grade. Families can purchase a hard copy of the guidelines from the State Department of Enterprise Services. A free downloadable version is available in English, Spanish, and Somali from DCYF’s Publication Library. Search by title: Washington State Early Learning and Development Guidelines, or publication number: EL_0015.

In Washington, the Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) administers services for eligible children from birth to age 3 through Early Support for Infants and Toddlers (ESIT). Families can contact ESIT directly, or they can reach out to their local school district to request an evaluation to determine eligibility and consider what support a child might need. The ESIT website includes videos to guide family caregivers and a collection of Parent Rights and Leadership resources, with multiple language options.

Early intervention services (EIS) are provided in the child’s “natural environment,” which includes home and community settings where children would be participating if they did not have a disability. According to ESIT, “Early intervention services are designed to enable children birth to 3 with developmental delays or disabilities to be active and successful during the early childhood years and in the future in a variety of settings—in their homes, in childcare, in preschool or school programs, and in their communities.”

Children who qualify receive services through an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). The right to an IFSP is protected by Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The IDEA is a federal grant program that provides funding for states to implement early learning and special education programs. Part B of the IDEA protects an eligible school-age student’s right to an Individualized Education Program (IEP). Part A includes general guidance about the educational rights of children 0-22.

Family caregivers, childcare professionals, teachers, or anyone else can refer a child for an early learning evaluation if there is reason to suspect that a disability or developmental delay may be impacting the child’s growth and progress. The school district’s duty to seek out, evaluate and potentially serve infants, toddlers or school-aged students with known or suspected disabilities is guaranteed through the IDEA’s Child Find Mandate.

Early intervention is intended for infants and toddlers who have a developmental delay or disability. Eligibility is determined by evaluating the child (with parental consent) to see if the little one does, in fact, have a delay in development or a disability. Eligible children can receive early intervention services from birth to the third birthday. PAVE provides an article that describes What Happens During an Early Intervention Evaluation, and a checklist for When Your Child is Found Eligible for Early Intervention Services (EIS).

If an infant or toddler is eligible, early intervention services are designed to meet the child’s individual needs. Options might include, but are not limited to:

Services are typically provided in the child’s home or other natural environment, such as daycare. They also can be offered in a medical hospital, a clinic, a school, or another community space.

The IFSP is a whole family plan, with the child’s primary caregivers as major contributors to its development and implementation. Parents/custodial caregivers must provide written consent for services to begin. In Washington, Family Resource Coordinators (FRCs) help write the IFSP. Team members may include medical professionals, therapists, child development specialists, social workers, and others with knowledge of the child and recommendations to contribute.

The IFSP includes goals, and progress is monitored to determine whether the plan is supporting appropriate outcomes. The plan is reviewed every six months and is updated at least once a year but can be reviewed at any time by request of parents or other team members. The IFSP includes:

PAVE provides a downloadable checklist to help parents familiarize themselves with the IFSP.

If parents have a concern or disagree with any part of the early intervention process, they can contact their Family Resource Coordinator (FRC). If issues remain unresolved, families may choose from a range of dispute resolution options that include mediation, due process, and more. ESIT provides access to a downloadable parent rights brochure with information about dispute resolution options in multiple languages.

Washington State provides most early intervention services at no cost to families of eligible children. Some services covered by insurance are billed to a child’s health insurance provider, with the signed consent of a family caregiver. The early intervention system may not use health care insurance (private or public) without express, written consent.

Part C of the IDEA requires states to provide the following services at no cost to families: Child Find (outreach and evaluation), assessments, IFSP development and review, and service coordination.

Military-connected infants and toddlers receiving early intervention services must be enrolled in the Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP) while their servicemember is on active-duty orders. The Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP) is a mandatory program for all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces that helps military dependents with special medical or educational needs. The Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force each have an EFMP and the Coast Guard, which operates under the authority of the Department of Homeland Security, has a similar program called the Special Needs Program (SNP).

The Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center (ECTA), funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education (OSEP), builds state and local capacity to improve outcomes for young children with disabilities and their families. Military-connected families and others relocating or living outside of Washington State can contact the early intervention services program in their new state with the help of ECTA’s Early Childhood Contacts by State directory.

Military families moving from or to installations that have Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) schools will receive their early intervention services from Educational and Developmental Intervention Services (EDIS). Referrals may come to EDIS from any military medical provider or the parents. Upon receipt of a referral to EDIS, an initial service coordinator is assigned to contact and assist the Family. The initial service coordinator gathers information to understand the family’s concern, shares information about early intervention, and makes arrangements to proceed with the process. In EDIS, any member of the early intervention team can serve as an initial service coordinator. EDIS is provided in locations where DoDEA is responsible for educational services, including some installations on the eastern side of the United States.

PAVE provides downloadable toolkits specifically designed for parents and families of young children:

For additional information:

A Brief Overview:

Full Article

The Procedural Safeguards are a written set of legal protections under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) designed to ensure that students with special needs receive appropriate education. IDEA, implemented under Washington State law, requires schools to provide the parents/guardians of a student who is eligible for or referred for special education with a notice containing a full explanation of the rights available to them (WAC 392-172A-05015). Understanding these safeguards allows for effective advocacy in a child’s education and ensures their rights are protected throughout the special education process. They do not constitute legal representation or legal advice.

A copy of the procedural safeguards notice is downloadable in multiple languages from the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). School districts must provide this notice once a year and during key times such as:

In addition to detailing when the procedural safeguards notice must be provided, the procedural safeguards contain information about several key areas, including:

Prior Written Notice

Schools must give prior written notice (PWN) before making any significant decisions about a student’s education, such as changes in identification, evaluation, or placement. This notice must include a detailed explanation of the decision and the reasons behind it. This document is shared after a decision is made and prior to changes in a student’s educational program.

Parental Consent

Schools must get written parental consent (permission) before conducting an initial evaluation or providing special education services for the first time. Parents can withdraw their consent at any time, but this doesn’t undo actions already taken. Once consent is given, the school has 35 school days to complete the evaluation. This consent is only for the evaluation, not for starting services. If the child is a ward of the state, consent might not be needed under certain conditions. When starting special education services under the initial IEP, the school must get consent again, and if refused, they can’t force it through mediation or legal action. Consent is also needed for reevaluations involving new tests, and schools must document their attempts to get it. However, consent isn’t needed to review existing data or give standard tests that all students take.

Independent Educational Evaluation

If a parent disagrees with the school’s evaluation of their child, they can ask for an independent educational evaluation (IEE) that the school district will pay for. The district must give the parent information on where to get an IEE and the rules it must follow. If the district does not agree to the IEE, they have 15 calendar days to either start a file a due process hearing request or agree to pay for the IEE. PAVE provides a downloadable sample Letter to Request an Independent Educational Evaluation.

Confidentiality of Information

Student educational records are confidential. IDEA provides parents and guardians the right to inspect and review their student’s educational records and request amendments if they believe they are inaccurate or misleading. When the child turns 18 years of age, these rights pass from the parent or guardian to the student. The Department of Education provides a website page called Protecting Student Privacy to share resources and technical assistance on topics related to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). The procedural safeguards explain terms about educational records from IDEA and FERPA to help parents understand their rights and protections.

Dispute Resolution

IDEA requires that each state education agency provide ways to solve disagreements between parents and schools regarding a student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). In Washington State, there are both informal and formal options. When parents and school districts are unable to work through disagreements, the procedural safeguards outline the dispute resolution processes available. These options ensure that parents and schools can work towards a mutually agreeable solution while protecting the child’s right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). The formal dispute resolution options available through OSPI are mediation, due process hearings, and state complaints.

Disciplinary Protections

When disciplining students eligible for special education, schools must follow specific rules to ensure fair treatment. If a student is removed for more than 10 consecutive school days or shows a pattern of removals totaling over 10 days in a school year, it’s considered a change of placement, and parents must be notified. After 10 days, the school must provide services to help the student continue their education. A manifestation determination must be conducted within 10 days to see if the behavior was related to the student’s disability. If it was, the IEP team must address the behavior and return the student to their original placement unless agreed otherwise. If not, the student can be disciplined like other students but must still receive educational services.

Also, schools must keep providing educational services to students with disabilities even if they are removed from their current school setting for disciplinary reasons. This helps the student keep making progress in their education. Parents and guardians have the right to join meetings about their child’s disciplinary actions and can ask for a due process hearing if they disagree with decisions. These safeguards ensure students with disabilities receive necessary support and fair treatment during disciplinary actions.

In special cases, such as carrying a weapon or using drugs at school, the student can be placed in an alternative setting for up to 45 days regardless of whether the behavior was related to the student’s disability.

Protections for Students Not Yet Eligible for Special Education

The procedural safeguards outline protections for students who have not yet been found eligible for special education but for whom the school should have known needed services. A school is considered to have this knowledge if a parent previously expressed concerns in writing, requested an evaluation, or if staff raised concerns about the student’s behavior to supervisory personnel. However, if the parent refused an evaluation or the child was evaluated and found ineligible, the school is not considered to have knowledge. In these cases, the student may be disciplined like other students, but if an evaluation is requested during this period, it must be expedited. If the student is found eligible, special education services must be provided.

Requirements for Placement in Private Schools

If parents believe the public school cannot provide FAPE and choose to place their child in a private school, there are steps to request reimbursement from the district. If the child previously received special education services, a court or administrative law judge (ALJ) may require the district to reimburse the cost of private school enrollment if it is determined that the district did not timely provide FAPE and that the private placement is appropriate, even if it does not meet state educational standards.

Reimbursement may be reduced or denied if the parent did not inform the IEP team of their rejection of the proposed placement during the most recent IEP meeting, failed to provide written notice to the district at least 10 business days before the removal, or did not make the child available for a district evaluation after prior written notice. However, reimbursement cannot be denied if the district prevented the notice or if the parent was unaware of their responsibility to provide it. The court or ALJ may also choose not to reduce reimbursement if the parents are not able to read or write in English, or if reducing or denying the reimbursement would cause serious emotional harm to the child.

This PAVE article, Navigating Special Education in Private School, explains the rights of students to receive equitable services in private schools, regardless of whether they are placed there by their parents or through an Individualized Education Program (IEP) decision.

Procedural Safeguards under Section 504

The procedural safeguards under Section 504 ensure that parents are informed of their rights before any evaluation or development of a 504 plan begins. These safeguards include the right to request a referral for evaluation, the formation of a 504 team to assess the student’s needs, and the requirement for parental consent before any evaluation or implementation of the plan. Parents must be provided with a copy of their rights at key points in the process. Additionally, the school must review and evaluate the 504 plan annually and re-evaluate the student’s eligibility at least every three years. Parents also have the right to file formal complaints if they believe the school is not following the 504 plan or if their child is experiencing discrimination or harassment. The Section 504 Notice of Parent Rights is available for download in multiple languages from OSPI.

Conclusion

Procedural safeguards are a requirement under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) that ensure the rights of students with disabilities and their parents are protected throughout the special education process. By outlining the legal protections available, these safeguards empower parents to actively participate in their child’s educational planning and decision-making. Understanding these rights—from prior written notice and parental consent to confidentiality and dispute resolution—allows families to advocate effectively and collaborate with schools. Through adherence to these safeguards, schools and parents can work together to provide a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) tailored to the unique needs of each child.

Additional Resources:

A Brief Overview:

Full Article

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that each state education agency provide ways to solve disagreements between parents and schools regarding a student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). These options ensure that parents and schools can work towards a mutually agreeable solution while protecting the child’s right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) offers both informal and formal dispute resolution processes.

These dispute resolution options provide structured processes for addressing and resolving disagreements, ensuring that the rights of students with special needs are upheld and that they receive the education and services to which they are entitled.

Informal Dispute Resolution

IEP facilitation is a voluntary and informal process where parents and school districts can address their special education concerns with the assistance of a trained, neutral facilitator. This process allows both parties to resolve issues collaboratively without the formality of mediation, and it is provided at no cost. OSPI contracts with Sound Options Group to offer free facilitation services from facilitators skilled in conflict resolution to help clarify disputes, set agendas, and work towards mutually agreeable solutions. Participation in facilitation is entirely optional for both families and districts.

The IEP facilitation process starts when either a family or a school district contacts the Sound Options Group to request help. A parent can request facilitation by contacting Sound Options Group directly by phone at 800-692-2540 or 206-842-2298 (Seattle) to request a mediation session. For Washington State relay service, dial 800-833-6388 (TDD) or 800-833-6384 (voice). Sound Options Group gathers initial information about the student and the needs of both parties, confirming that both the family and district agree to proceed with a facilitated IEP meeting. Once the IEP team sets a date for the 3–4-hour meeting, the facilitator is assigned. The facilitator helps everyone prepare by sharing documents, setting a mutually agreeable agenda, confirming the meeting details, and preparing both parties for the meeting. After the facilitated IEP meeting, a case worker from Sound Options Group and the facilitator review the session and decide if another meeting is needed. A successful facilitated IEP meeting will result in the development of an IEP that is tailored to meet the unique needs of the student.

Another option for informal dispute resolution is Washington State Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds (OEO), which helps parents and schools resolve disagreements about special education services. Acting as a neutral and independent guide, the OEO helps parents and educators understand special education regulations, facilitates problem-solving, and advises on communication strategies to support a team approach to a student’s education. The OEO does not provide legal advice, act as an attorney, conduct investigations, or advocate for any party. OEO can be contacted through their online intake form or by phone (1-866-297-2597) with language interpretation available.

Formal Dispute Resolution

When informal methods are unsuccessful, families and schools can turn to formal dispute resolution processes outlined in the procedural safeguards and available through the special education system. A copy of the procedural safeguards notice for Washington is downloadable in multiple languages from the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI).

In Washington state, the formal dispute resolution options are:

1. Mediation

Mediation is a voluntary process provided at no cost to parents and schools. It is designed to resolve disputes related to the identification, evaluation, educational placement, and provision of FAPE. Both parties must agree to participate in mediation. Mediators are trained, impartial individuals knowledgeable about special education laws. OSPI contracts with Sound Options Group to provide trained, neutral mediators to facilitate effective communication and problem-solving between parents and school districts. This brochure, Mediation in Special Education, outlines the services provided by Sound Options Group. Discussions during mediation are confidential and cannot be used in due process hearings or civil proceedings. If an agreement is reached, it must be documented in writing and is legally binding. Parents can contact Sound Options Group directly to request mediation.

2. Special Education Complaint

Any individual or organization can file a special education complaint if they believe a school district or public agency has violated Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Complaints must be filed within one year of the alleged violation. OSPI investigates the complaint, gathering information from both the parent or guardian and the school district. OSPI then issues a written decision addressing the complaint and any corrective actions required within 60 days of receiving the complaint. PAVE has developed this training video, Procedural Safeguards: How to File a Special Education Complaint, that walks through OSPI’s community complaint form with a pretend scenario.

3. Due Process Hearing

A due process hearing is a formal meeting to resolve disputes about a child’s identification, evaluation, placement, or FAPE. Either parents or the school district can request this hearing, but they must do so within two years of the issue, unless there was misrepresentation or withheld information. The request for a due process hearing must be in writing, signed, and include:

The original request must be provided to the other party – the parent or guardian must send it to the superintendent of the student’s school district, and the school district must provide the original to the parent or the guardian of the student. In addition, a copy of the request must be sent to the Office of Administrative Hearings by mail (PO Box 42489, Olympia, WA 98504-2489), fax (206-587-5135), or email (oah.ospi@oah.wa.gov). The party asking for a due process hearing must have proof that they gave their request to the other party.

Before the hearing, the school district must meet with the parents and relevant IEP team members within 15 days to try to resolve the issue at a resolution session. OSPI provides a direct to download form, Information and Forms on Resolution Sessions. During the hearing, both sides present evidence and witnesses. Parents have the right to bring a lawyer, present evidence, and question witnesses. An administrative law judge (ALJ) makes a decision, which can be appealed in state or federal court. The decision is final unless it is appealed and the decision is overturned. If an agreement is reached before the hearing, it must be written down in a settlement agreement.

For disputes about disciplinary actions that change a student’s placement, expedited due process hearings are available. These hearings happen faster than regular ones to resolve urgent issues quickly.

Dispute Resolution Outside of Special Education

If parents disagree with the decision made in a due process hearing, they have the right to file a civil lawsuit in state or federal court. This must be done within a specific time period, often 90 days, after the due process hearing decision. The court will review the administrative record, hear additional evidence if necessary, and make a ruling (decision) in the case. The civil lawsuit is not a part of the special education dispute resolution process and there are additional costs associated. Please note that PAVE is not a legal services agency and cannot provide legal advice or representation. Washington State Office of Administrative Hearings has compiled this Legal Assistance List for Special Education Due Process Disputes.

If parents win a due process hearing or lawsuit, the school district might have to pay their attorneys’ fees. But if the court decides the complaint was frivolous or filed for the wrong reasons, parents might have to pay the school district’s attorneys’ fees.

Additional Considerations

If a child hasn’t been identified as needing special education but parents think they should be, there are protections if the child faces disciplinary actions. If the school knew the child might need special education services before the behavior happened, they must follow special education disciplinary procedures.

Every school district has a process for filing a formal complaint related to harassment, intimidation and bullying (HIB). PAVE has compiled information and resources to address bullying in this article, Bullying at School: Resources and the Rights of Students with Special Needs.

Complaint Processes Related to Discrimination

OSPI’s Complaints and Concerns About Discrimination page states, “Each student must have equal access to public education without discrimination.” This page contains Discrimination Dispute Resolution Information Sheets that contain definitions of key terms, information about the role of district Civil Rights Compliance Coordinators, and instructions and requirements for filing different types of complaints, available for download in different languages. Anyone can file a complaint about discrimination involving students with disabilities in a Washington public school, which is prohibited by Washington law (RCW 28A.642.010). Formal discrimination complaints must be written, and the complaint must contain:

The formal discrimination complaint must be hand carried, mailed, faxed, or emailed to district superintendent, administrator of the charter school, or Civil Rights Coordinator. When a school district or charter school receives a complaint, it must investigate and respond within 30 days, unless an extension is agreed upon. The civil rights coordinator provides the complaint procedure and ensures a thorough investigation. If exceptional circumstances require more time, the school must notify the complainant in writing. The school can also resolve the complaint immediately if both parties agree. After the investigation, the school must respond in writing, summarizing the results, stating whether they complied with civil rights law, explaining appeal options, and detailing any corrective measures, which must be implemented within 30 days unless otherwise agreed.

Students with disabilities in public schools are also protected against discrimination by federal laws, including Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and IDEA. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) accept complaints with overlapping civil rights concerns, such as racism and disability discrimination. An OCR complaint must be filed within 180 calendar days of the alleged discrimination. If the school district’s dispute resolution process is already handling the case through a means like what OCR would provide, OCR will not take on the case. Once the school district’s process is completed, individuals have 60 days to file their complaint with OCR, which will then decide whether to accept the result from the other process. OCR provides step-by-step instructions for filing a discrimination complaint.

Some families are anxious about questioning actions taken by the school. Parents have protections under the law. The Office for Civil Rights maintains specific guidelines that prohibit retaliation against people who assert their rights through a complaint process.

Additional Resources:

When a student has unmet needs and may need new or different school-based services, figuring out what to do next can feel confusing or overwhelming. PAVE provides this toolkit to support families in taking initial, critical steps. These guidelines apply regardless of where school happens.

Presenting our newest resource – the Where To Begin When a Student Needs Help. This user-friendly toolkit has been created to give you and your family the guidance you need when you are navigating the special education process in Washington State.

A user – friendly toolkit for families, Each section is detailed below: