A Brief Overview

- Governor Jay Inslee announced April 6, 2020, that Washington school buildings are closed to regular instruction at least through the end of the school year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- During the shutdown, schools and families are seeking creative ways to help all children learn, said Washington’s Superintendent of Public Instruction, Chris Reykdal, who participated in the April 6 press conference with Gov. Inslee. “Especially during times of uncertainty,” Reykdal said, “students need our support. They need grace, and structure, and routine. Even though the world may feel like it’s upside down, our students need to know that we will move forward.”

- PAVE’s program to provide Parent Training and Information (PTI) continues to offer 1:1 support by phone in addition to online learning opportunities. Please refer to our home page at wapave.org to “Get Help” or to check the Calendar for upcoming events. A PTI webinar recorded live March 26, 2020, provides information about the rights of students with disabilities.

- For questions about delivery of special education during the school building closures, families also can visit the website of the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), which maintains a page, Special Education Guidance for COVID-19. Ways to support inclusion during the closures and a downloadable spreadsheet of online and offline resources for continuing learning are clickable links on that page.

- Providing families with access to meals has been a priority for schools. An interactive map on the website of Educational Service District 113 includes information from schools across Washington about where meals are delivered and addresses for where families can pick up free food by “Grab-and-Go.”

- The U.S. Department of Education has created a website page to address COVID-19. Links on the website, gov/coronavirus, include a Fact Sheet titled, Addressing the Risk of COVID-19 in Schools While Protecting the Civil Rights of Students, issued by the department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

- For additional resources, see Links to Support Families During the Coronavirus Crisis and Links for Learning at Home During School Closure.

Full Article

With school buildings closed to help slow the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), families have many questions about how children can access meals, childcare and basic education. Recognizing that too much information can be overwhelming, PAVE provides this article to help families with children impacted by disability understand a few key issues during this challenging time. Included throughout are links to information on official websites that are frequently updated.

Nationally, agencies that provide guidance to schools have been in conversation about the challenge of providing equitable education to all students as learning that respects the requirement for “social distancing” becomes the only option. The U.S. Department of Education is tracking much of that work on its website, gov/coronavirus.

Most schools in Washington resumed services with distance learning on March 30, 2020. Some districts planned a later start because of spring break schedules. Chris Reykdal, Washington’s Superintendent of Public Instruction, issued guidance that all schools within the state offer something in order to engage students in learning.

He emphasized that families and schools should maintain an attitude of creativity and patience and that the goal is not to overwhelm parents and students. The guidance is not a mandate for students, Reykdal said, and the state is not directing schools to grade student work during this period of distance learning. The expectation is that districts “are sending opportunities for families and checking in,” he said in comments quoted in a March 30 broadcast and article from KNKX, a National Public Radio affiliate.

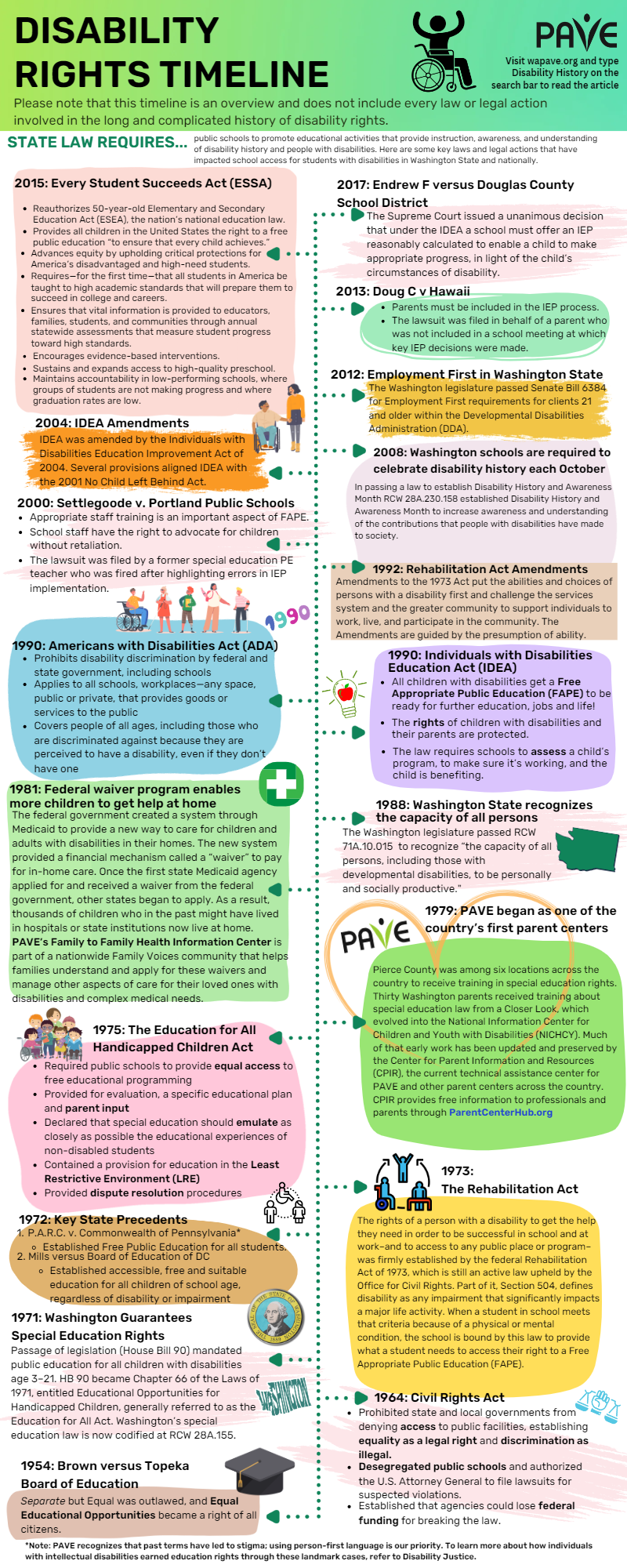

Various federal and state laws protect students with disabilities and their right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), regardless of the nature or severity of the disability. How to provide education that is appropriate and equitable when school buildings are closed is a national conversation. In Washington State, the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) is continuously updating guidance for schools and families on these topics.

An OSPI website page devoted to special education topics during the COVID-19 shutdown includes this guidance: “If the district continues providing education opportunities to students during the closure, this includes provision of special education and related services, too, as part of a comprehensive plan.”

In a March 18, 2020, letter to school staff who support Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), OSPI encouraged IEP reviews and evaluations to continue as possible: “School districts are encouraged to continue to hold IEP and evaluation meetings through distance technology whenever possible, and if agreed upon by parents and school staff are available.”

Meals are a top priority

The Superintendent of Public Instruction, Chris Reykdal, provided information March 19, 2020, in a webinar sponsored by the Washington League of Education Voters. Note: the League of Education Voters offers a comprehensive listing of COVID-19 resources.

Reykdal said that OSPI has prioritized food distribution for students as its most important role during the shutdown. He said some districts deliver food to stops along regular bus routes. Others have food pick-up available in school parking lots. For the most current information about how a district is making meals available for students, families are encouraged to check their local district website or call the district office. OSPI provides a list of districts throughout the state, with direct links to district websites and contact information.

An interactive map on the website of Educational Service District 113 includes information from schools across Washington about where meals are delivered and addresses for where families can pick up free food by “Grab-and-Go.”

Childcare options are difficult to design

Second priority, according to Reykdal, is childcare for parents who rely on outside help so they can work. Families are encouraged to contact local districts for current information about childcare. OSPI encourages only small and limited gatherings of children, so provisions for childcare and early learning have been difficult to organize, Reykdal said. He emphasized that public health is the top concern. “We have to flatten that curve,” he said, referencing a widely shared graphic that shows what may happen if the virus is not slowed by intentional measures.

Note that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid have relaxed rules in order to give states more flexibility in providing medical and early learning services through remote technologies. The Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center (ECTA) has created a webpage on teleintervention. Topics include training for families learning to navigate technology for online learning and appointments.

Equity is required in education

Thirdly, Secretary Reykdal on March 19 addressed work underway to create new models for distance learning. “Everyone needs to be super patient about this because while districts are preparing to deploy some education, it will look different. And there are serious equity concerns we have to focus on. We expect districts as they launch this to have an equitable opportunity for all students. English language learners need special supports. Our students with disabilities need supports.”

At the April 6, 2020, press conference, Reykdal mentioned that some schools may open on a very limit basis in order to provide services to a few children with significant disabilities. He said OSPI would be consulting with schools throughout the state to develop models for best-practice IEP implementation during the national crisis. “Especially during times of uncertainty,” he said, “students need our support. They need grace, and structure, and routine. Even though the world may feel like it’s upside down, our students need to know that we will move forward.”

PAVE is here to help!

PAVE’s Parent Training and Information (PTI) program continues to provide 1:1 support by phone and offers online training. Please check our calendar of events and follow us on social media.

PTI director Jen Cole addressed some topics related to educational access during a March 19, 2020, podcast hosted by Once Upon a Gene. In addition to providing general information about the rights of students with disabilities, Cole shares her own experience as a parent of an elementary-age student with a disability.

PAVE has added new links on our website to help families navigate these new circumstances. On our homepage, wapave.org, find the large blue button labeled View Links. Clicking on that button will open a list of options. Two new options provide guidance related to the pandemic:

- Links for Learning at Home During School Closure: This a resource collection of agencies providing online learning opportunities for various ages.

- Links to Support Families During the Coronavirus Crisis: This is a resource collection of agencies that provide information related to the pandemic.

Please note that resources listed are not affiliated with PAVE, and PAVE does not recommend or endorse these programs or services. These lists are not exhaustive and are provided for informational purposes only.

OSPI offers guidance for families

The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) is the state education agency charged with overseeing and supporting Washington’s 295 public school districts and seven state-tribal education compact schools. As communities respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, OSPI offers a downloadable guide for parents and families.

Included is a section for parents of students in special education. While in session, districts maintain the responsibility to provide a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) to students eligible for special education. “Districts should be communicating with parents and guardians prior to, during, and after a school closure regarding their child’s IEP services,” OSPI states.

Parents may want to consider whether compensatory education or Extended School Year (ESY) services will be needed. The general rights to these services are further described in an article about ESY on PAVE’s website.

Making notes in order to collect informal data about any regression in learning during the shutdown may be important later. OSPI’s resource guide states: “After an extended closure, districts are responsible for reviewing how the closure impacted the delivery of special education and related services to students eligible for special education services.”

OSPI reminds families that schools are not required to provide special education services while they are fully closed to all students.

OSPI addresses issues related to racism

In its guidance, OSPI encourages schools to intentionally and persistently combat stigma through information sharing: “COVID-19 is not at all connected to race, ethnicity, or nationality.”

OSPI advises that bullying, intimidation, or harassment of students based on actual or perceived race, color, national origin, or disability (including the actual disability of being infected with COVID-19 or perception of being infected) may result in a violation of state and federal civil rights laws:

“School districts must take immediate and appropriate action to investigate what occurred when responding to reports of bullying or harassment. If parents and families believe their child has experienced bullying, harassment, or intimidation related to the COVID-19 outbreak, they should contact their school district’s designated civil rights compliance coordinator.”

U.S. Department of Education provides written guidance and a video

The U.S. Department of Education provides a website page to address COVID-19. Links on the website, ed.gov/coronavirus, include a Fact Sheet titled, Addressing the Risk of COVID-19 in Schools While Protecting the Civil Rights of Students, issued by the department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR):

“Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibits disability discrimination by schools receiving federal financial assistance. Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 prohibits disability discrimination by public entities, including schools. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits race, color, and national origin discrimination by schools receiving federal funds….

“School districts and postsecondary schools have significant latitude and authority to take necessary actions to protect the health, safety, and welfare of students and school staff….As school leaders respond to evolving conditions related to coronavirus, they should be mindful of the requirements of Section 504, Title II, and Title VI, to ensure that all students are able to study and learn in an environment that is safe and free from discrimination.”

On March 21, 2020, the department issued a Supplemental Fact Sheet to clarify that the department does not want special education protections to create barriers to educational delivery options: “We recognize that educational institutions are straining to address the challenges of this national emergency. We also know that educators and parents are striving to provide a sense of normality while seeking ways to ensure that all students have access to meaningful educational opportunities even under these difficult circumstances.

“No one wants to have learning coming to a halt across America due to the COVID-19 outbreak, and the U.S. Department of Education does not want to stand in the way of good faith efforts to educate students on-line. The Department stands ready to offer guidance, technical assistance, and information on any available flexibility, within the confines of the law, to ensure that all students, including students with disabilities, continue receiving excellent education during this difficult time.”

The Department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) released a YouTube video March 17, 2020, to describe some ways that OCR is providing technical assistance to schools attempting to offer online learning that is disability accessible. Kenneth L. Marcus, assistant secretary for civil rights within the Department of Education, opens the video by describing federal disability protections:

“Online learning is a powerful tool for educational institutions as long as it is accessible for everyone. Services, programs and activities online must be accessible to persons, including individuals with disabilities, unless equally effective alternate access is provided in another manner.”

Help is available from Parent Training and Information (PTI)

Families who need direct assistance in navigating special education process can request help from PAVE’s Parent Training and Information Center (PTI). PTI is a federally funded program that helps parents, youth, and professionals understand and advocate for individuals with disabilities in the public education system. For direct assistance, click “Get Help” from the home page of PAVE’s website: wapave.org.

PTI’s free services include:

- Training, information and assistance to help you be the best advocate you can be

- Navigation support to help you access early intervention, special education, post-secondary planning and related systems in Washington State

- Information to help you understand how disabilities impact learning and your role as a parent or self-advocate member of an educational team

- Assistance in locating resources in your local community

- Training and vocabulary to help you understand concepts such as Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), an entitlement for individuals who qualify for special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).