A Brief Overview

- A student with a disability has the right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). General education spaces and curriculum are LRE.

- Services are generally portable, and special education is delivered to the student to enable access to FAPE within the LRE to the maximum extent appropriate.

- Federal law protects a student’s right to FAPE within the LRE in light of a child’s circumstances, not for convenience of resource allocation.

- The TIES Center at the University of Minnesota partnered with the Haring Center for Inclusive Education at the University of Washington to build a resource for families and schools writing IEPs to support students within general education: Comprehensive Inclusive Education: General Education and the Inclusive IEP.

Full Article

An ill-informed conversation about special education might go something like this:

- Is your child in special education?

- Yes.

- Oh, so your student goes to school in that special classroom, by the office…in the portable…at the end of the hall…in a segregated room?

This conversation includes errors in understanding about what special education is, how it is delivered, and a student’s right to be included with general education peers whenever and wherever possible.

This article intends to clear up confusion. An important concept to understand is in the headline:

Special Education is a service, not a place!

Services are portable, so special education is delivered to the student in the placement that works for the student to receive a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), in light of the child’s circumstances. A student with a disability has the right to FAPE in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE).

General education is the Least Restrictive Environment. An alternative placement is discussed by the student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) team if access to FAPE is not working for the student in a general education setting with supplementary aids and supports.

Keep in mind that genuine inclusion doesn’t just meet a seat in the classroom. Adult support, adaptations to the learning materials, individualized instruction, and more are provided to support access to education within the LRE.

Here is some vocabulary to further understanding:

- FAPE: Free Appropriate Public Education. The entitlement of a student who is eligible for special education services.

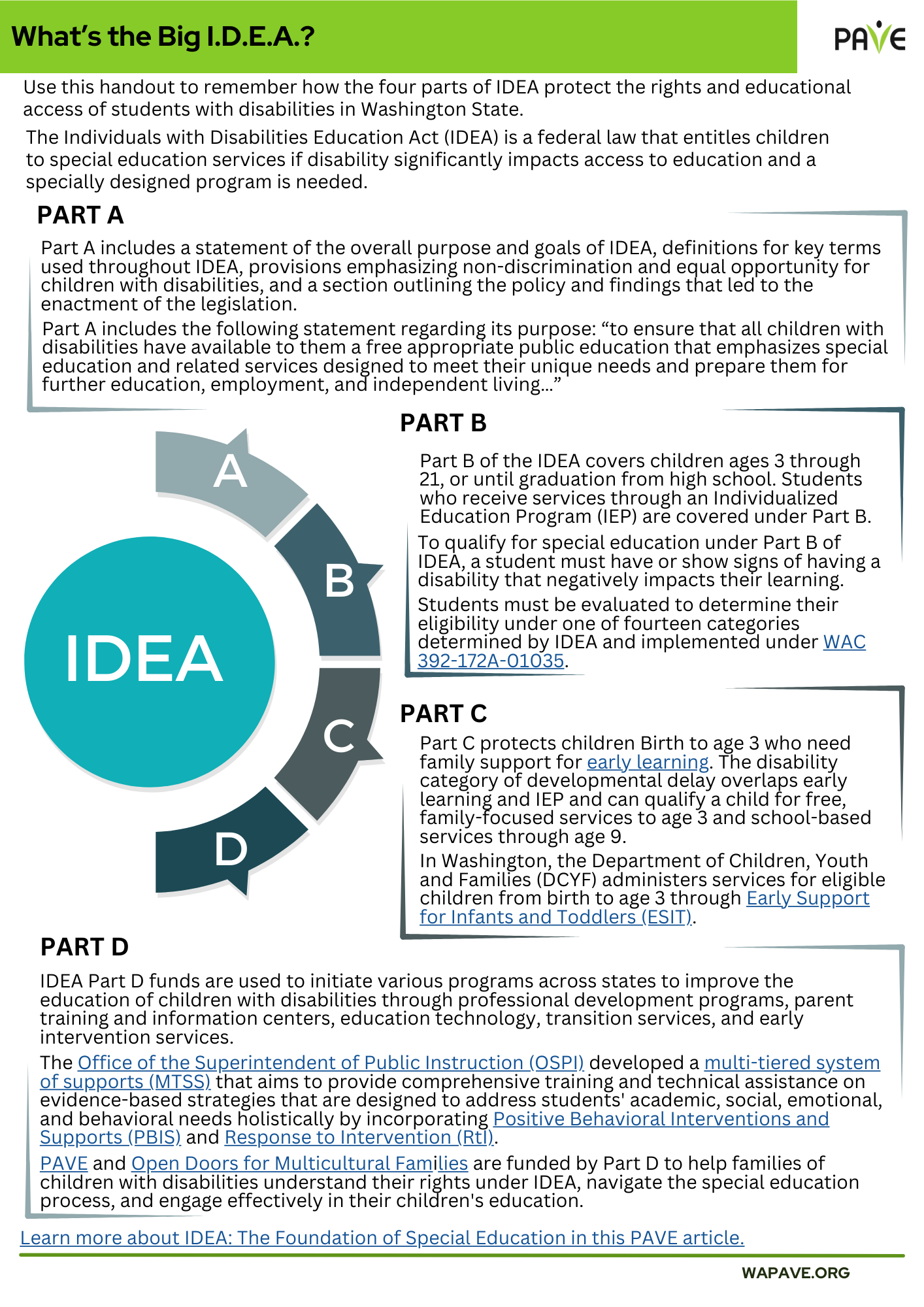

- IDEA: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The entitlement to FAPE is protected by this law that allocates federal funds to support eligible students.

- LRE: Least Restrictive Environment. A student eligible for special education services has a right to FAPE in the LRE to the maximum extent appropriate. General education is the least restrictive, and an alternative placement is discussed when data indicate that supplementary aids and supports are not working to enable access to FAPE in general education.

- IEP: Individualized Education Program. School staff and family caregivers make up an IEP team. The team is responsible to develop a program reasonably calculated to enable a student to make progress appropriate toward IEP goals and on grade-level curriculum, in light of the child’s circumstances. Based on a student’s strengths and needs (discovered through evaluation, observation, and review of data), the team collaborates to decide what services enable FAPE and how to deliver those services. Where services are delivered is the last part of the IEP process, and decisions are made by all team members, unless family caregivers choose to excuse some participants or waive the right to a full team process.

- Equity: When access is achieved with supports so the person with a disability has a more level or fair opportunity to benefit from the building, service, or program. For example, a student in a wheelchair can access a school with stairs if there is also a ramp. A person with a behavioral health condition might need a unique type of “ramp” to access equitable learning opportunities within general education.

- Inclusion: When people of all abilities experience an opportunity together, and individuals with disabilities have supports they need to be contributing participants and to receive equal benefit. Although IDEA does not explicitly demand inclusion, the requirement for FAPE in the Least Restrictive Environment is how inclusion is built into special education process.

- Placement: Where a student learns. Because the IDEA requires LRE, an IEP team considers equity and inclusion in discussions about where a student receives education. General education placement is the Least Restrictive Environment. An IEP team considers ways to offer supplementary aids and supports to enable access to LRE. If interventions fail to meet the student’s needs, the IEP team considers a continuum of placement alternatives—special education classrooms, alternative schools, home-bound instruction, day treatment, residential placement, or an alternative that is uniquely designed.

- Supplementary Aids and Supports: The help and productivity enhancers a student needs. Under the IDEA, a student’s unique program and services are intended to enable access to FAPE within LRE. Note that an aid or a support is not a place and therefore cannot be considered as an aspect of a restrictive placement. To the contrary, having additional adult support might enable access to LRE. This topic was included in the resolution of a 2017 Citizen Complaint in Washington State. In its decision, OSPI stated that “paraeducator support is a supplementary aid and service, not a placement option on the continuum of alternative placements.”

Note that the IDEA protects a student’s right to FAPE within LRE in light of a child’s circumstances, not in light of the most convenient way to organize school district resources. Placement is individualized to support a student’s strengths and abilities as well as the needs that are based in disability.

Tip: Families can remind the IEP team to Presume Competence and to boost a student from that position of faith. If the team presumes that a student can be competent in general education, how does it impact the team’s conversation about access to FAPE and placement?

LRE does not mean students with disabilities are on their own

To deliver FAPE, a school district provides lessons uniquely designed to address a student’s strengths and struggles (Specially Designed Instruction/SDI). In addition, the IEP team is responsible to design individualized accommodations and modifications. (Links in this paragraph take you to three PAVE training videos on these topics.)

- Accommodations: Productivity enhancers. Examples: adjusted time to complete a task, assistive technology, a different mode for tracking an assignment or schedule, accessible reading materials with text-to-speech or videos embedded with sign language…

- Modifications: Changes to a requirement. Examples: an alternative test, fewer problems on a worksheet, credit for a video presentation or vision board instead of a term paper.

Note that accommodations and modifications are not “special favors.” Utilizing these is an exercise of civil rights that are protected by anti-discrimination laws that include the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (particularly Section 504 as it relates to school) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA—particularly Title II).

Related Services may support LRE and other aspects of equitable access

An IEP may include related services (occupational therapy, speech, nursing, behavioral or mental health support, parent training, transportation, and more). For some students, related services may be part of the support structure to enable inclusion in the Least Restrictive Environment. If an IEP includes related services, then the IEP team discusses how and where they are delivered.

A tool to support inclusion

The TIES Center at the University of Minnesota partnered with the Haring Center for Inclusive Education at the University of Washington to build a resource to support families and schools in writing IEPs that support students within general education classrooms: Comprehensive Inclusive Education: General Education and the Inclusive IEP.

The resource includes a variety of tools and recommendations for how school and family teams can approach their meetings and conversations to support the creation and provision of a program that recognizes:

- Each child is a general education student.

- The general education curriculum and routines and the Individual Education Program (IEP) comprise a student’s full educational program.

- The IEP for a student qualifying for special education services is not the student’s curriculum.

Who is required on an IEP team?

Keep in mind that IEP teams are required to include staff from general education and special education (WAC 392-172A-03095). All team members are required for formal meetings unless the family signs consent for those absences. Here’s a key statement from the TIES Center resource:

“The IEP is intended to support a student’s progress in general education curriculum and routines, as well as other essential skills that support a student’s independence or interdependence across school, home, and other community environments. A comprehensive inclusive education program based upon these principles is important because without that focus, a student’s learning opportunities and school and post-school outcomes are diminished. In order to create an effective comprehensive inclusive education program, collaboration between general educators, special educators, and families is needed.”

LRE decisions follow a 4-part process

OSPI’s website includes information directed toward parents: “Placement decisions are made by your student’s IEP team after the IEP has been developed. The term ‘placement’ in special education does not necessarily mean the precise physical building or location where your student will be educated. Rather, your student’s ‘placement’ refers to the range or continuum of educational settings available in the district to implement her/his IEP and the overall amount of time s/he will spend in the general education setting.”

Selection of an appropriate placement includes 4 considerations:

- IEP content (specialized instruction, goals, services, accommodations…)

- LRE requirements (least restrictive “to the maximum extent appropriate”)

- The likelihood that the placement option provides a reasonably high probability of helping a student attain goals

- Consideration of any potentially harmful effects the placement option might have on the student, or the quality of services delivered

What are placements outside of general education?

If a student is unable to access appropriate learning (FAPE) in general education because their needs cannot be met there, then the IEP team considers alternative placement options. It’s important to note that a student is placed in a more restrictive setting because the student needs a different location within the school, not because it’s more convenient for adults or because it saves the school district money.

According to IDEA, Sec. 300.114, “A State must not use a funding mechanism by which the State distributes funds on the basis of the type of setting in which a child is served that will result in the failure to provide a child with a disability FAPE according to the unique needs of the child, as described in the child’s IEP.”

IEP teams may discuss whether there’s a need for a smaller classroom setting or something else. Keep in mind that a home-based placement is a very restrictive placement because it segregates a student entirely from their peers.

The continuum of placement options includes, but is not limited to:

- general education classes

- general education classes with support services and/or modifications

- a combination of general education and special education classes

- self-contained special education classes

- day treatment, therapeutic school specializing in behavioral health

- private placement outside of the school district (non-public agency/NPA)

- residential care or treatment facilities (also known as NPAs)

- alternative learning experience (ALE)

- home-based placement

School districts are not required to have a continuum available in every school building. A school district, for example, might have a self-contained setting or preschool services in some but not all locations. This gives districts some discretion for choosing a location to serve the placement chosen by an IEP team.

Placement and location are different

Note that the IEP team determines the placement, but the school district has discretion to choose a location to serve the IEP.

For example, an IEP team could determine that a student needs a day treatment/behavioral health-focused school in order to access FAPE—an appropriate education. If the IEP team chooses a Day Treatment placement, then the school district is responsible to find a location to provide that placement. Following this process, a public-school district might pay for transportation and tuition to send a student to a private or out-of-district facility. If a request for a specialized placement is initiated by the family, there are other considerations.

OSPI’s website includes this information:

“… if you are requesting that your student be placed in a private school or residential facility because you believe the district is unable to provide FAPE, then you must make that request through a due process hearing.”

Resources about inclusionary practices

An agency called Teaching Exceptional Children Plus features an article by a parent about the value of inclusion in general education. The January 2009 article by Beth L. Sweden is available for download online: Signs of an Inclusive School: A Parent’s Perspective on the Meaning and Value of Authentic Inclusion.

Understood.org offers an article and a video about the benefits of inclusion.

An agency that promotes best-practice strategies for school staff implementing inclusive educational programming is the IRIS Center, a part of Peabody College at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

As stated earlier, The TIES Center at the University of Minnesota partnered with the Haring Center for Inclusive Education at the University of Washington to build a resource for families and schools writing IEPs to support students within general education: Comprehensive Inclusive Education: General Education and the Inclusive IEP.

The Inclusionary Practices Family Engagement Collaborative is a partnership of four non-profit organizations committed to strengthening family-school partnerships to support culturally-responsive approaches that center the experiences of students with disabilities. Watch recorded trainings offered to help you start the conversation.