Homeschooling is a popular and flexible educational option for many families. “Home-based instruction” (HBI), as it’s referred to in Washington State law, must meet specific required subjects and instructional hours (or school days) annually. If you’re considering homeschooling, it’s important to understand the legal requirements and steps involved, including the qualifications that make a parent or guardian eligible to provide home-based instruction. Homeschooled students can access public school resources like extracurricular activities, part-time classes, and even special education services. By understanding and adhering to these guidelines, you can ensure a successful and enriching homeschooling experience for your child.

A Brief Overview

- Homeschooling or home education programs are called “home-based instruction (HBI)” in Washington state.

- A parent or guardian must meet one of four qualifying criteria to homeschool, or register through an approved private school extension program.

- Homeschooling must cover 11 required subjects and at least 1,000 instructional hours annually (or 180 school days), but Washington law (RCW 28A.200.020) allows for flexibility in teaching methods and curriculum selection, emphasizing a personalized approach.

- Beginning on their eighth birthday, your child must be enrolled in a school or home-based instruction, in accordance with Washington’s compulsory attendance law (RCW 28A.225.010).

- If your student was enrolled in school prior to homeschooling and they are 8 years of age or older, they must be withdrawn by written and signed statement, and you must file a Declaration of Intent with your local public school district. The Declaration of Intent must be filed by September 15th annually, or within two weeks of the beginning of the public school year.

- Homeschooled children must complete yearly assessments, either through standardized testing or an evaluation by a certificated educator. Parents and guardians must keep the results in their homeschooling files as a permanent record.

- Families can request a special education evaluation from the public school district regardless of whether their child is enrolled in public school. If the child is eligible, the district must provide ancillary services unless the family declines them (RCW 28A.150.350).

- Homeschooled students can participate in public school resources, including part-time enrollment in virtual or in-person classes, extracurricular activities, and sports.

- PAVE provides a downloadable Annual Checklist for Home-Based Instruction to help families maintain compliance with Washington’s homeschool statutes.

Introduction

Whether you are looking for an alternative to public school or continuing a home education program you began before moving from out of state, there are some things you need to know before homeschooling your student in Washington State. Homeschooling, referred to as “home-based instruction (HBI)” in the state statutes, comes with specific guidelines and requirements.

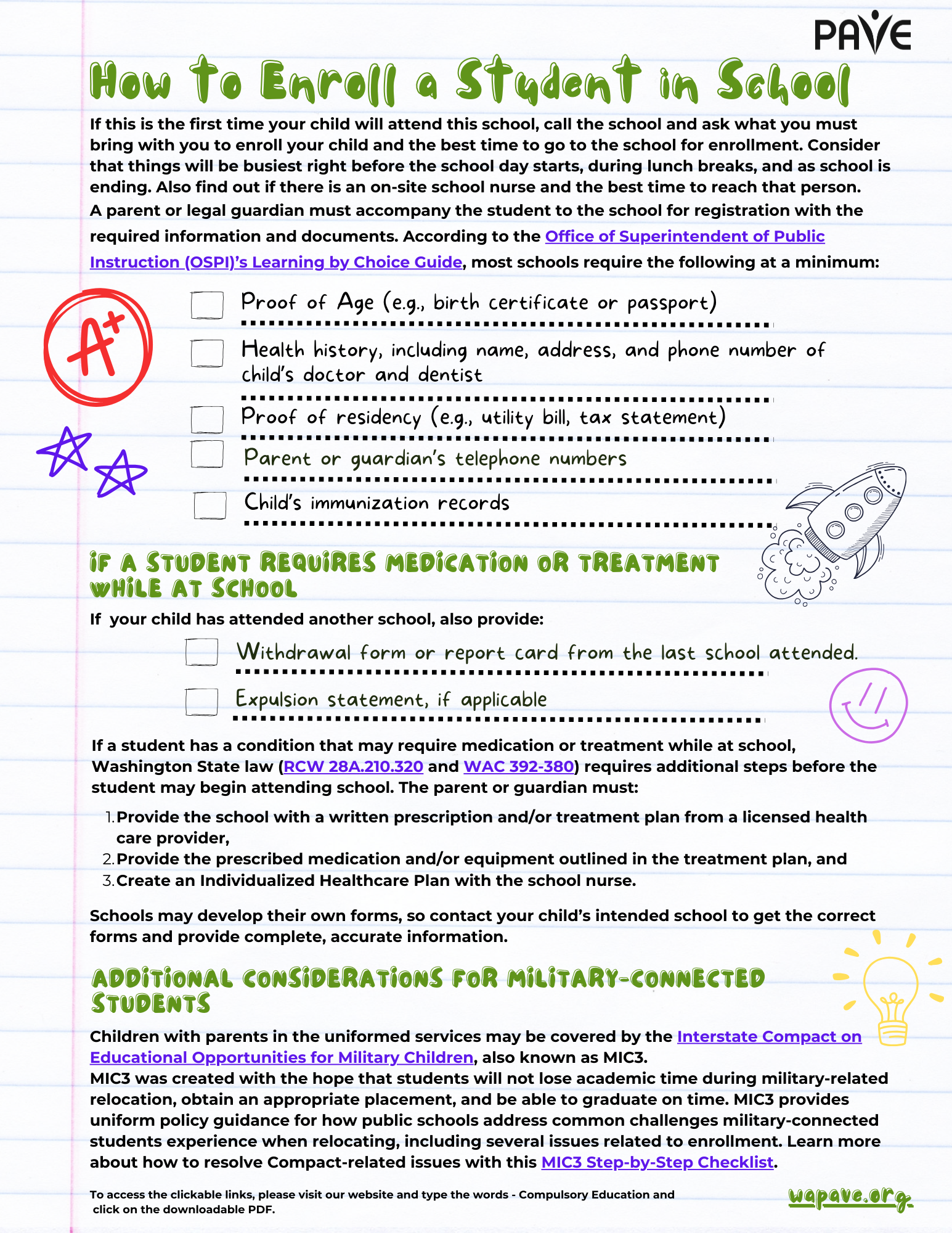

To homeschool, a parent or guardian must:

- Meet the qualifications for homeschooling under state law (RCW 28A.225.010(4))

- Provide 180 school days or 1,000 instructional hours annually in the 11 required subjects

- Formally withdraw the student from public school

- Notify the school district of annually with a Declaration of Intent

- Have the student complete an annual test or assessment

- Maintain homeschool records

What qualifications must a parent or guardian meet to homeschool?

A parent or guardian has to meet one of the following qualifications to homeschool their child:

- Hire a certified teacher to supervise the instruction.

- Complete 45 college quarter credits or the equivalent in semester credits.

- Complete a course in home-based education, sometimes referred to as a parent qualifying course, at a postsecondary or vocational-technical institute.

- Gain approval from the superintendent as “sufficiently qualified to provide home-based instruction.” Those who have homeschooled in another state and move into Washington may be more successful with this by demonstrating a documented history of homeschooling.

If you do not meet these qualifications, you may homeschool through a private school extension program. Locate an approved private school that allows the homeschooling option and contact the school directly.

What do homeschool students learn?

Washington law mandates that homeschooled children receive at least 1,000 instructional hours annually (or 180 school days), similar to the public school system. There are 11 required subjects, although parents do not have to teach every subject daily, weekly, or even yearly. Some subjects, like social studies, are for younger grades, while others, like history, are for older grades. The homeschool curriculum must include the following subjects:

- Occupational education

- Science

- Math

- Language

- Social studies

- History

- Health

- Reading

- Writing

- Spelling

- Art and music appreciation

You have full control over your homeschooling curriculum, allowing you to tailor the education to your child’s needs and interests. You are responsible for decisions related to educational philosophy, selection of books, teaching materials, curriculum, and methods of instruction (RCW 28A.200.020).

Washington law acknowledges that “home-based instruction is less structured and more experiential than the instruction normally provided in a classroom setting.” As a result, the nature and quantity of instructional and educational activities are “construed liberally”. This flexibility gives you the freedom to create a personalized educational experience. (RCW 28A.225.010(5))

When and how can I withdraw my student from public school?

Children living in Washington must be enrolled in a school or home-based instruction starting on their eighth birthday. The law requires compulsory attendance from age eight until eighteen (RCW 28A.225.010). Any educational programs your child participates in before age eight are not subject to state requirements for home-based instruction.

If your child is enrolled in a public or private school and you decide to homeschool, you must first formally withdraw your student. This process involves submitting a withdrawal form provided by the school or a written statement including the student’s name, school name, date of withdrawal, your signature, and the date of signing.

If your child is 8 years of age or older, notify the school district of your intent to homeschool on the same day that you withdraw them from public school, even if they have not yet begun classes or an educational program at the school.

How do I notify the school district that I am homeschooling my child?

For every school year that your child is homeschooled, you must file a written statement, called a Declaration of Intent, with the district superintendent. The address of the superintendent is usually the district office, which you can find on the school’s website or by calling your local school. You may retain a district-stamped copy of the Declaration of Intent by including a second copy and a self-addressed envelope with prepaid postage in your mailer. The deadline to file is September 15th or within two weeks of the beginning of the public school year.

A Declaration of Intent is not required for children who begin school before age 8. For example, a 5-year-old who has started kindergarten may be withdrawn for home-based instruction. The child started going to school before compulsory attendance applied. As a result, the parent is not required to file a Declaration of Intent. If you intend to start your student’s educational career in homeschool, submit your first Declaration of Intent when your child turns 8 years old and compulsory education begins.

The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) has provided a Sample Declaration of Intent that includes all of the required information: the child’s name, age, address, and parent’s name. This documents that the parent is complying with compulsory education requirements, and the student is receiving an education. The Declaration of Intent must also specify whether a certified teacher will supervise the instruction.

What are my options to complete the required annual assessments?

There are two options for the required annual assessments:

- Standardized Test: Administered annually by a qualified individual approved by the test publisher. The test must be a standardized academic achievement test recognized by Washington State Board of Education (SBE). For a list of examples of tests, see the SBE Home Instruction FAQs page.

- Annual Assessment: Conducted by a certificated person currently working in the field of education. The evaluation must be written. Washington law does not provide as much detail about the criteria for evaluations, but it should include “statements and documents that reflect the child’s progress, or lack thereof” (OSPI).

The purpose of the annual test or evaluation is to provide an external metric to measure a student’s progress. The results are for the parent’s use only, unless the child is later enrolled at a public or private school. Parents can choose either option each year based on what works best for their child. Keep the test results in your permanent homeschool record.

Homeschooled students may take part in standardized testing at the public school. The testing dates for the year are usually available at the school office by late September and parents can call the assessment coordinator at the school district to register their student for these tests. Be sure to request a copy of the test scores for your homeschooling file during registration for the standardized test.

If a homeschooled student performs poorly on a test or assessment and the results indicate that they are “not making reasonable progress consistent with his or her age or stage of development,” the parent or guardian is expected to “make a good faith effort to remedy any deficiency”. (RCW28A.200.010(1)(c))

What records do homeschooled students have?

Maintaining good records is an essential part of homeschooling in Washington state, serving as proof of education and compliance with state laws. While the law does not specify the exact form records should take, there are several types of documentation that are meaningful for homeschooled students:

- Attendance records tracking the 180 school days or 1,000 instructional hours required

- Curriculum information documenting the textbooks and workbooks used

- Student work samples and portfolios demonstrating application of what they’ve learned

- Communication with school officials, including the annual Declaration of Intent and proof of mailing, such as the Certified Mail-Return Receipt

- Test results, such as annual standardized tests and assessments

- Immunization records

These records can be requested by school administrators if your child later enrolls in a traditional school setting. You should permanently keep proof of compliance with home education laws, including the Declaration of Intent and results of the annual assessments. Homeschool Legal Defense Association (HSLDA) recommends keeping all records from your student’s high school years because they may be requested as proof of education by a post-secondary education program, upon joining the military, or as part of an employment-related background check.

Does the public school have to provide special education and related services to homeschooled students?

Families have the right to request an evaluation for special education from the public-school district regardless of whether a child attends public school. If the child is found eligible, the local district is responsible for providing services unless the family does not want them. In some cases, families arrange to have a child attend private or home-based school but receive special-education services through the public school. These special education services are known as “ancillary services” and they are defined in Washington Administrative Code (WAC) as “any cocurricular service or activity, any health care service or activity, and any other services or activities, except ‘courses,’ for or in which preschool through twelfth grade students are enrolled by a public school” (WAC 392-134-005).

Ancillary services include but are not limited to:

- Therapies, such as counseling, speech and hearing therapy

- Counseling and health services

- Testing and assessments

- Supplementary or remedial instruction

- Tutorial services, which may include home or hospital instruction

- Sports activities

According to The Pink Book: Washington State Laws Regulating Home-Based Instruction, available on OSPI’s Home-Based Instruction page, the definition of “course” specifies that a service or activity meets all of the requirements of an ancillary service but is instructional in nature.

Can homeschooled students take part in public school classes or activities?

Students homeschooled in Washington have access to public school resources, including standardized testing, extracurricular activities, and specialized programs. Families can enroll their children as part-time students to access specific classes or services that complement their home-based instruction (RCW 28A.150.350(d)). Homeschooled students can attend virtual and online public school programs on a part-time basis without losing their homeschool status.

Access to extracurricular activities includes participation in sports and other interscholastic competitions through the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association (WIAA). Homeschooled students are considered “regular members” as long as they have met the State’s home-based instruction requirements, and –

- Annually file a WIAA Rule 18.6.3 form with the principal’s office where the student is enrolled part-time. This form is available on the WIAA website, on the Student Eligibility Center page in multiple languages.

- Do not receive assistance from the school district, and the school district does not receive funding for the student.

- Meet both WIAA and the local school district eligibility requirements.

- Follow transfer rules if they change schools after registering as a homeschool student.

- Provide acceptable documentation of any interscholastic eligibility standards required of all other student participants.

- Comply with WIAA and local school district regulations during participation.

- Adhere to the same team responsibilities and standards of behavior and performance as other team members.

- Participate as a member of the public school in the service area where they reside.

Final Thoughts

Homeschooling in Washington State provides families with a flexible and personalized approach to education while adhering to the state’s legal requirements. By understanding and meeting the necessary qualifications, maintaining proper records, and fulfilling annual assessment obligations, parents and guardians can ensure their child’s education remains compliant and effective. The wide array of resources, from specialized classes to extracurricular activities, further supports a well-rounded learning experience. Whether you are new to homeschooling or continuing from another state, Washington’s supportive framework allows for a rich and adaptable educational journey tailored to each child’s unique needs.