Epilepsy is a brain condition that causes people to have seizures. There are many different types of seizures, and each person’s experience with epilepsy can be different. Today, doctors have better ways to treat epilepsy, and there are more resources to help families. Even though some people still don’t understand epilepsy, support and awareness are growing.

A Brief Overview

- Epilepsy is a brain condition that affects people in different ways and can cause different types of seizures.

- People with epilepsy may also have other health conditions, like Autism, depression, ADHD, learning disabilities, or migraines.

- In the past, people with epilepsy were often kept away from others because of fear and misunderstanding.

- New medicines like Phenobarbital and Dilantin have helped many people control their seizures and live more normal lives.

- Parents and caregivers help children with epilepsy, get the help they need at school and with doctors.

- Special epilepsy centers give full care, including tests, support, and sometimes surgery.

Introduction

Epilepsy is a brain condition that causes people to have seizures. There are many different types of seizures, and each person’s experience with epilepsy can be different. Today, doctors have better ways to treat epilepsy, and there are more resources to help families. Even though some people still don’t understand epilepsy, support and awareness are growing.

Understanding Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological disease and a spectrum disorder. A person diagnosed with epilepsy is at a higher risk of having a seizure. A seizure occurs when there is a sudden, temporary burst of electrical activity in the brain that changes or disrupts the messages to the brain cells. The electrical bursts result in involuntary changes in body movement or function, sensation, behavior, and possible loss of consciousness/awareness of surroundings.

As technology has become more advanced, the medical community has discovered that there are many distinct types of epilepsy and different causes. Each person diagnosed with epilepsy has a unique experience. Epilepsy includes many types of seizures, grouped into three main categories based on where abnormal electrical activity occurs in the brain. The most common seizures are:

- Tonic-clonic seizure: A tonic-clonic seizure causes loss of consciousness and violent muscle contractions.

- Absence seizure: An absence seizure causes brief losses of consciousness and looks like a person is staring into space.

- Focal aware seizure: During a focal aware seizure, the person is alert and aware that the seizure is occurring. The person may feel tingling sensations or have body movements that they cannot control. Previously called, simple partial seizure.

- Tonic seizure: In a tonic seizure the muscles contract making the arms and legs very rigid. The seizures usually occur at night when the person is sleeping.

- Myoclonic seizure: A myoclonic seizure is a brief shock-like jerk of a muscle or muscle group. The person may not even realize it has occurred.

- Atonic seizure: Atonic seizures cause the muscles to go limp. Sometimes the person’s eyes may droop, and their heads will nod forward. If a person is standing up, and all their muscles go limp, they will fall.

In addition to the variations in seizures, epilepsy has other common health conditions linked to the diagnosis of epilepsy. Young children diagnosed with epilepsy are now automatically evaluated for autism, as research has shown a connection between the two conditions. Depression is the most common co-occurring health condition with epilepsy. Other health conditions commonly linked to epilepsy include ADHD, Learning Challenges, Anxiety, Mood Disorders and Migraines.

A Look Back: The History of Epilepsy Treatment in the U.S.

In the 1940s, people with epilepsy were often treated very differently than they are today. At that time, people with epilepsy were called “victims.” Back then, many families kept their loved ones with epilepsy at home and away from others because they were afraid of how people would react to seizures.

Doctors sometimes sent people with epilepsy to live in special communities, often on farms. These places were made to be safe and self-sufficient. People grew their own food, and workers helped with cooking and cleaning to prevent injuries during seizures. But these communities also kept people with epilepsy separated from the rest of society.

Things started to change when new anticonvulsant medicines, like Phenobarbital and Dilantin, were discovered. These drugs helped many people control their seizures and return to living at home. Both drugs are still in use today. Even with treatment, it was still hard for people with epilepsy to find jobs because of fear and misunderstanding.

By the 1960s, most of the special communities had closed. While treatment improved, people with epilepsy still faced stigma. Today, there is more awareness and support, but work continues to make sure everyone with epilepsy is treated fairly.

Advocacy in Action – From National Organizations to Parent -Led movements

Many years ago, several epilepsy organizations across the United States recognized the need to work together to better support individuals living with epilepsy. Groups like the National Association to Control Epilepsy, American Epilepsy League, and the National Epilepsy League each had their own ideas about how to organize and share responsibilities. It took more than 20 years of discussion and collaboration before they successfully united to form a single national organization: the Epilepsy Foundation.

Today, the Epilepsy Foundation plays a leading role in supporting people with epilepsy and their families. It offers reliable information about epilepsy and seizures, connects families to local support groups and resources, and advocates for better care and services. The Foundation also funds research to improve treatments and works closely with local chapters to ensure families can access help in their own communities.

In its early years, the Foundation was led mostly by medical researchers focused on developing treatments. Over time, it expanded to include the voices of families, caregivers, and community advocates. This broader involvement helped shape the Foundation’s mission and made it more responsive to the needs of those it serves.

In 1998, Susan Axelrod and a small group of parents started CURE Epilepsy to support research aimed at finding a cure for epilepsy, motivated by their experiences with treatment-resistant seizures in their children. CURE stands for Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy, and it is the only nonprofit organization solely dedicated to funding research to find a cure by supporting innovative science that targets the root causes of epilepsy.

Educational Advocacy for Children with Epilepsy

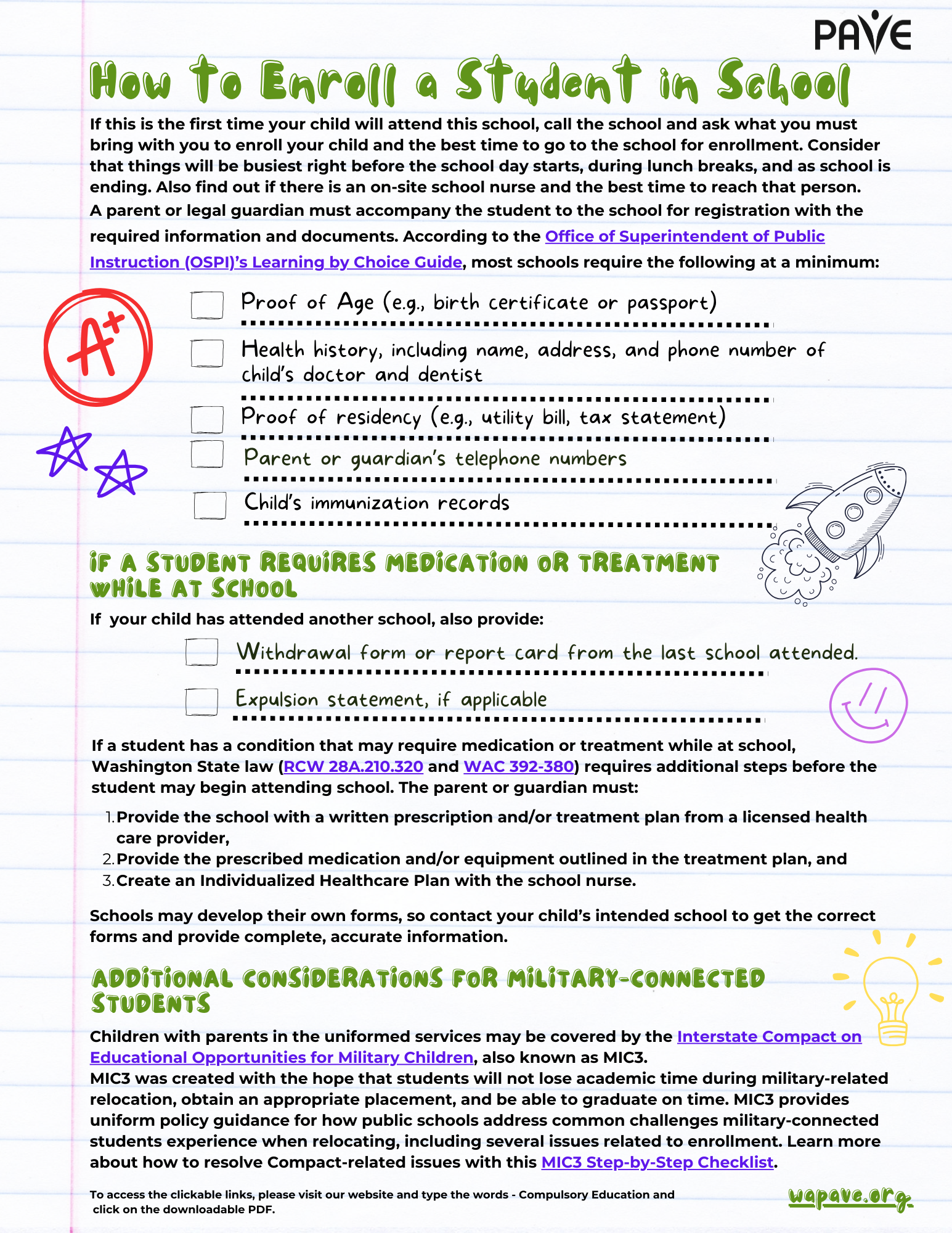

Parents and family caregivers of children with epilepsy often play a key role in ensuring their child receives the support they need at school. Because epilepsy can affect learning, attention, memory, and behavior, especially when seizures are frequent or medications cause side effects, educational advocacy is essential.

Working with schools to develop individualized plans that support their child’s learning and safety, families may advocate for:

- Section 504 Plans: These provide accommodation such as extra time on tests, rest breaks, or permission to carry and take medication at school.

- Individualized Education Programs (IEPs): For students whose epilepsy significantly impacts learning, an IEP outlines specialized instruction and services tailored to their needs.

- Medical Action Plans: Parents collaborate with school staff to create emergency plans that explain how to recognize and respond to their child’s seizures.

Modern Treatments and Family Support

Today, children with epilepsy can get care at special medical centers called pediatric epilepsy centers. These centers focus on both the child and their family. They are designed to help children who still have seizures after trying two different medicines for at least three months.

Some of the services these centers may offer include:

- A place to stay for longer testing and care

- Support from social workers for both the child and family

- Help from other doctors and therapists who work with the child

- Neurosurgery, if it might help reduce or stop seizures

In Washington State, some examples of these centers are:

- Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center

- Seattle Children’s Epilepsy Program

- Swedish Epilepsy Center at Cherry Hill Campus

- UW Medicine Regional Epilepsy Center at Harborview

Families can also get help outside of the hospital. For example, PAVE provides information, resources, and parents for parents and individuals with disabilities in Washington State. If your infant or toddler has just been diagnosed with epilepsy, they may be eligible for early intervention services. PAVE provides an article, Early Intervention: How to Access Services for Children Birth to 3 in Washington, to support families in understanding the steps to get started, what services are available, and how to advocate for their child’s needs. Students and their families can contact PAVE for personalized support and training with IEPs, 504 plans, and medical action plans by completing the online help request form.

Parents can also join online support groups specifically for parents of children with epilepsy, or be matched with another parent who has been through a similar experience through the Parent-to-Parent program. If you are a family living in Pierce County, PAVE offers family support activities, information, and referrals through the Pierce Parent to Parent Program.

Final Thoughts

Understanding and awareness of epilepsy has come a long way over the years. Thanks to better medicine, more knowledge, and strong support from families and organizations, people with epilepsy can live full and active lives. There are still some challenges, like helping others understand what epilepsy is and making sure everyone gets the care they need. But with continued support and awareness, the future looks brighter for people living with epilepsy.

Learn More

Epilepsy-specific information, support groups, and resources:

Level 3 Epilepsy Centers:

Pediatric Level 4 Epilepsy Centers: