Families can request an IEP (Individualized Education Program) meeting at any time—not just during the annual review. A sample letter is available to help parents and guardians formally make this request. Guidance is also provided on who must attend IEP meetings, common reasons for requesting one, and tips for organizing communication and documentation.

A Brief Overview:

- Families can request an IEP meeting at any time—not just during the annual review.

- Washington state law (WAC 392-172A-03095) requires that the IEP team include specific people and roles.

- Common reasons to request a meeting include academic struggles, behavior concerns, new diagnoses, or transition planning.

- Students can also request meetings to advocate for themselves or adjust goals and supports.

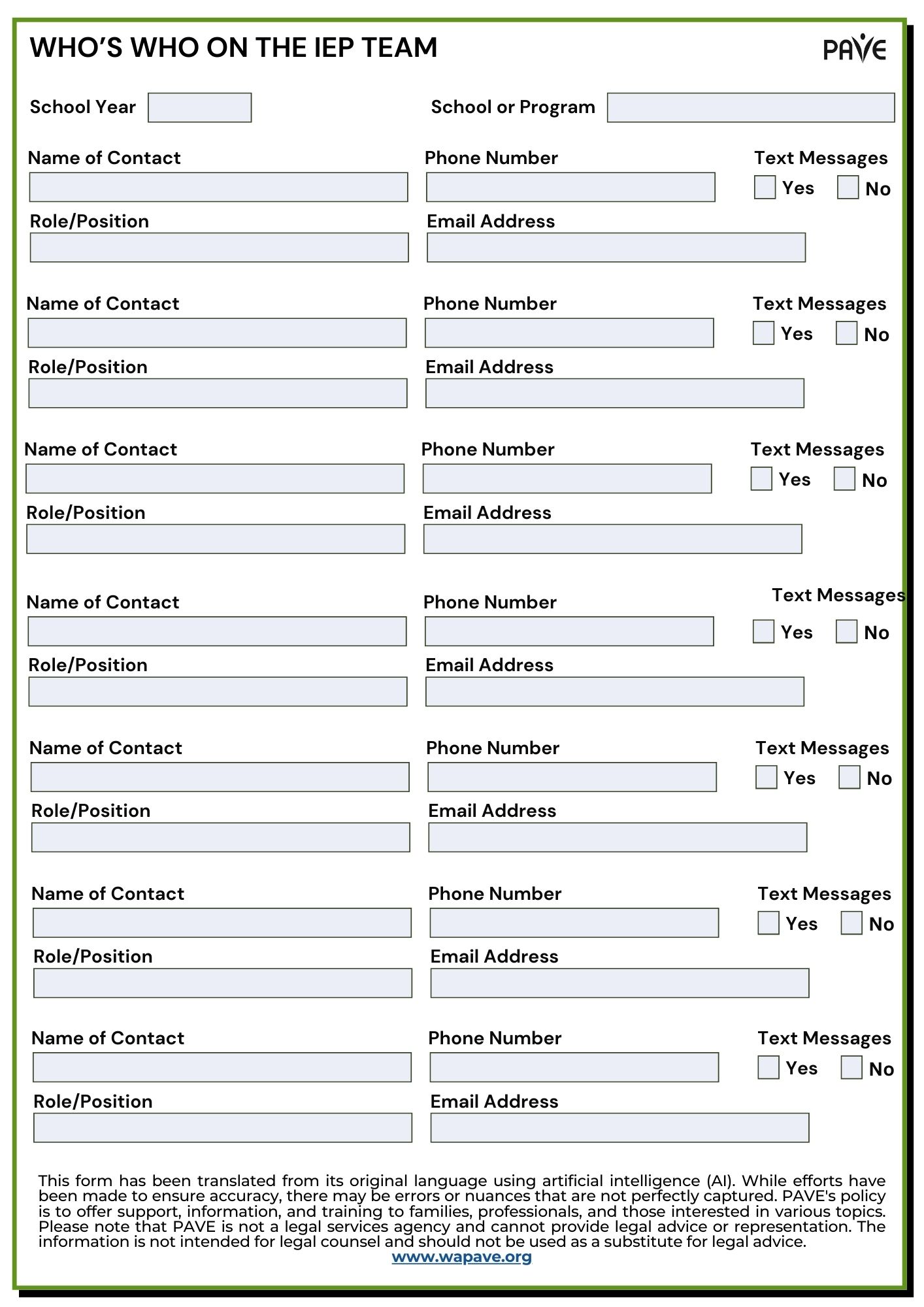

- PAVE offers helpful tools to support families in preparing for IEP meetings, including a fillable Who’s Who on the IEP Team contact form and sample letter to formally request a meeting—both available for download in multiple languages within this article.

Introduction

When a student has an Individualized Education Program (IEP), their IEP team is required to meet and review the program at least every year. The annual review date is listed on the cover page of the IEP document. Family caregivers can request additional meetings, and this article includes a sample letter families can use to formally request an IEP meeting.

Keep in mind that parents have the right to participate in meetings where decisions are made about eligibility or changes to a student’s special education services. A court decision in 2013 further affirmed those rights. More information about that case, Doug C. Versus Hawaii, is included in the PAVE article, Parent Participation in Special Education Process is a Priority Under Federal Law.

An IEP meeting request letter can be submitted to school staff and to district staff. Family participants have the right to invite guests to the meeting for support and to provide additional expertise about the student.

Required Members of the IEP Team

The best practice is for the school and parents to communicate about who will attend the meeting. If required school staff are unable to attend a meeting, parents must sign consent for their absence. Under Washington Administrative Code (WAC 392-172A-03095), a school district must ensure that each IEP team includes:

- Parent/legal guardian

- At least one general education teacher

- At least one special education teacher of the student

- District staff qualified in the provision of specially designed instruction (SDI), knowledgeable about the district’s general education curriculum, and knowledgeable about the district’s available resources

- Someone (usually a school psychologist) qualified to interpret the instructional implications of evaluation results

- At the discretion of the parent or the school district, other individuals who have knowledge or special expertise regarding the student, including related services personnel

- Whenever appropriate, the student (required to be invited once a transition plan is added, by age 16 or earlier)

According to Washington state law (WAC 392-172A-03095), the IEP team includes an individual who is knowledgeable about district resources. Sometimes a school principal or other staff member fulfills that role, but families or school staff can request attendance by someone who works in the district’s special education department. If a school administrator says during a meeting, “We’ll have to check with the district and get back to you,” it may mean that a key decision-maker isn’t present. In that case, families or students can request another meeting with all required team members. This is especially important if the team is discussing services that might cost more or involve a change in the student’s educational placement.

The school’s meeting invitation lists attendees and can clarify when the meeting will start and end and the purpose or agenda for the meeting. PAVE provides an article about how students and families can prepare for a meeting by creating a handout for the team, including a Student Input Form.

Who’s Who on the IEP Team

PAVE offers a fillable Who’s Who on the IEP Team contact form to help you organize contact information and roles of the IEP team members.

Download the Who’s Who on the IEP Team contact form in:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Ukrainian українська | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

Common Reasons to Request an IEP Meeting

Parents, guardians, and students have the right to request an IEP team meeting at any time during the school year—not just during the annual review. If there are concerns about a student’s progress, changes in needs, or questions about services and supports, it’s appropriate to ask for the team to come together. IEP meetings can be used to problem-solve, update goals, adjust services, or simply ensure everyone is on the same page. Regular communication helps keep the plan relevant and responsive to the student’s needs.

Here are a few examples of reasons parents or guardians might request an IEP meeting:

- New diagnosis or information about a student’s disability

- Frequent disciplinary actions

- Student is refusing to go to school

- Academic struggles

- Lack of meaningful progress toward IEP goals (PAVE provides an article with a handout about SMART goals and progress monitoring)

- Behavior plan isn’t working

- Placement isn’t working

- Parent or guardian wants to discuss further evaluation by the school or an independent agency

Here are a few examples of reasons parents or guardians might request an IEP meeting:

- Feeling unsupported in class

- Academic struggles

- Trouble with peers or behavior plan

- Goals don’t feel meaningful or realistic

- Preparing for life after high school (transition planning is required by age 16)

- New diagnosis or change in personal circumstances

- Practicing self-advocacy or wanting a more active role in the IEP process

PAVE provides a sample letter to request an IEP meeting. You can copy and paste the text of this sample letter into your word processor to build your own letter. If sending through email, the format can be adjusted to exclude street addresses.

Sample Letter to Request an IEP Meeting

PAVE provides a sample letter to request an IEP meeting. You can copy and paste the text of this sample letter into your word processor to build your own letter. If sending through email, the format can be adjusted to exclude street addresses.

Download the Sample Letter to Request an IEP Meeting in:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Ukrainian українська | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

You can email this letter or send it by certified mail (keep your receipt), or hand carry it to the district office and get a date/time receipt. Remember to keep a copy of this letter and all school-related correspondence for your records. Get organized with a binder or a filing system that will help you keep track of all letters, meetings, conversations, etc. These documents will be important for you and your child for many years to come, including when your child transitions out of school.