A Brief Overview

Each student has abilities and skills. A thoughtful Individualized Education Program (IEP) can highlight abilities and provides the supports needed for the student to learn. This article will help parents understand how to participate in the IEP process.

Every part of the IEP is measured against this question: How does this help the student with disabilities receive the support needed to access a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)? Read on to learn more about FAPE and other important parts of special education.

Learn the 5 steps a parent can take as a member of the IEP team. This article will help you gear up for the school year.

The Parent Training and Information (PTI) team at PAVE are here to help: If you need 1:1 help navigating the IEP process, click Get Help! on our website, wapave.org.

Full Article

A new school year is a great time to take a fresh look at your student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). If your student doesn’t have an IEP and you wonder if a disability might be impacting your student’s learning, this is a good time to learn about the special education process. This article will help you learn the basics. You can also read PAVE’s article about Evaluation, the first step in the IEP process.

As you and your student get ready for school, the most important thing is the “I” in IEP. The “I” is for “Individualized,” so no two IEPs are the same! Your student has abilities and skills. A thoughtful IEP highlights abilities and helps your student access the supports needed to learn. With an IEP, a student with disabilities can make meaningful progress in school. It also prepares your student for life after high school. An IEP is a team effort, and parents and students who learn about the process and fully participate get on a path for success.

FAPE is an acronym you want to know

When Congress passed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990, special education got its most important acronym: FAPE. FAPE stands for Free Appropriate Public Education. The right to FAPE makes the IDEA law unique: It is the only law in the United States that provides an individual person with the right to a program or service that is designed just for that person. This is called an entitlement.

Entitlement means that a student with disabilities is served on an individual basis, not based on a system or program that’s already built and available.

When schools and parents talk about a special education program, they talk about the services and instruction that a student needs to learn in school. Every part of the IEP is measured against this question: How does this help the student receive the support needed to access a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)?

Education is a civil right. Students have the right to access a free, public education through the age of 21. Students with disabilities identified through an evaluation process qualify for FAPE. Let’s take a closer look at the second word in FAPE: Appropriate. When an education is “appropriate,” it is designed to fit a specific student. Like a custom-made garment, it fits the learning style, capacity and specific needs of the student without any gaps.

The IDEA is based on an earlier law: The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975. This federal law was the first one that required schools to create specific educational plans for students with disabilities. In 1972 a Washington, D.C., court said that education should be free and “suitable” for all children of school age, regardless of disability or impairment.

Parents can keep this in mind when they read through the IEP or when they prepare for IEP meetings. They can ask, Is the program or service suitable and appropriate, given my student’s abilities and circumstances?

To qualify for an IEP a student is evaluated to see if there is a disability that is causing an adverse educational impact. The educational evaluation may show that the student has a disability that matches at least one of the 14 categories that are listed in the IDEA. Those categories are:

|

Autism

|

Deaf-blindness

|

Deafness

|

|

Emotional Disturbance

|

Hearing Impairment

|

Intellectual Disability

|

|

Multiple Disabilities

|

Orthopedic Impairment

|

Other Health Impairment

|

|

Specific Learning Disability

|

Speech/Language Impairment

|

Traumatic Brain Injury

|

|

Visual Impairment/Blindness

|

Developmental Delay (ages 0-8)

|

|

If the student, with parent input, is determined to “meet criteria” under the IDEA, then that student is eligible for special education services. Special education is a service, not a place.

Current federal law includes six important principles

The IDEA, which has been amended a few times since 1990, includes some important elements for parents. Here’s a brief overview:

- Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE): Students with disabilities who need a special kind of teaching or other help have the right to an education that is designed just for them.

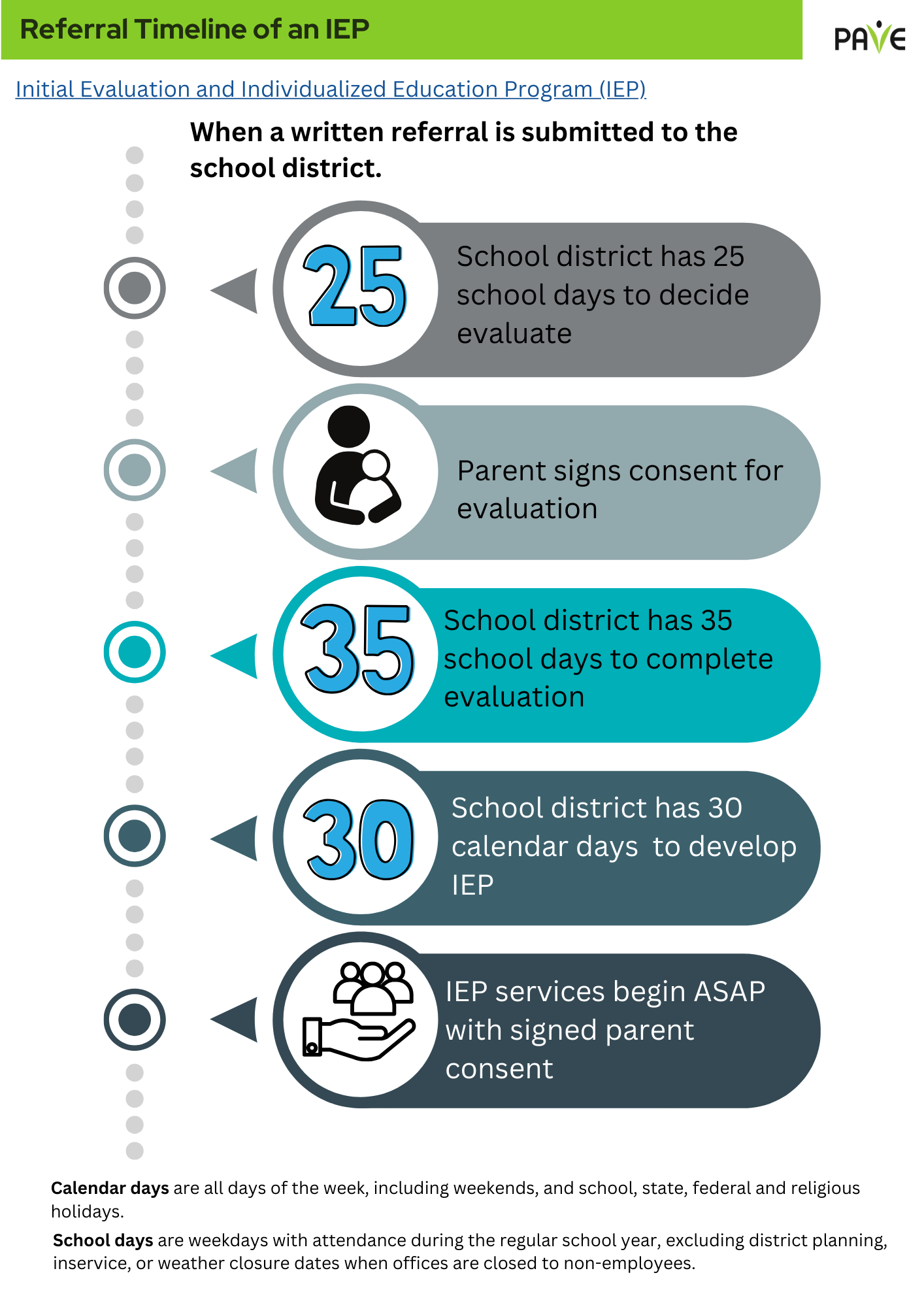

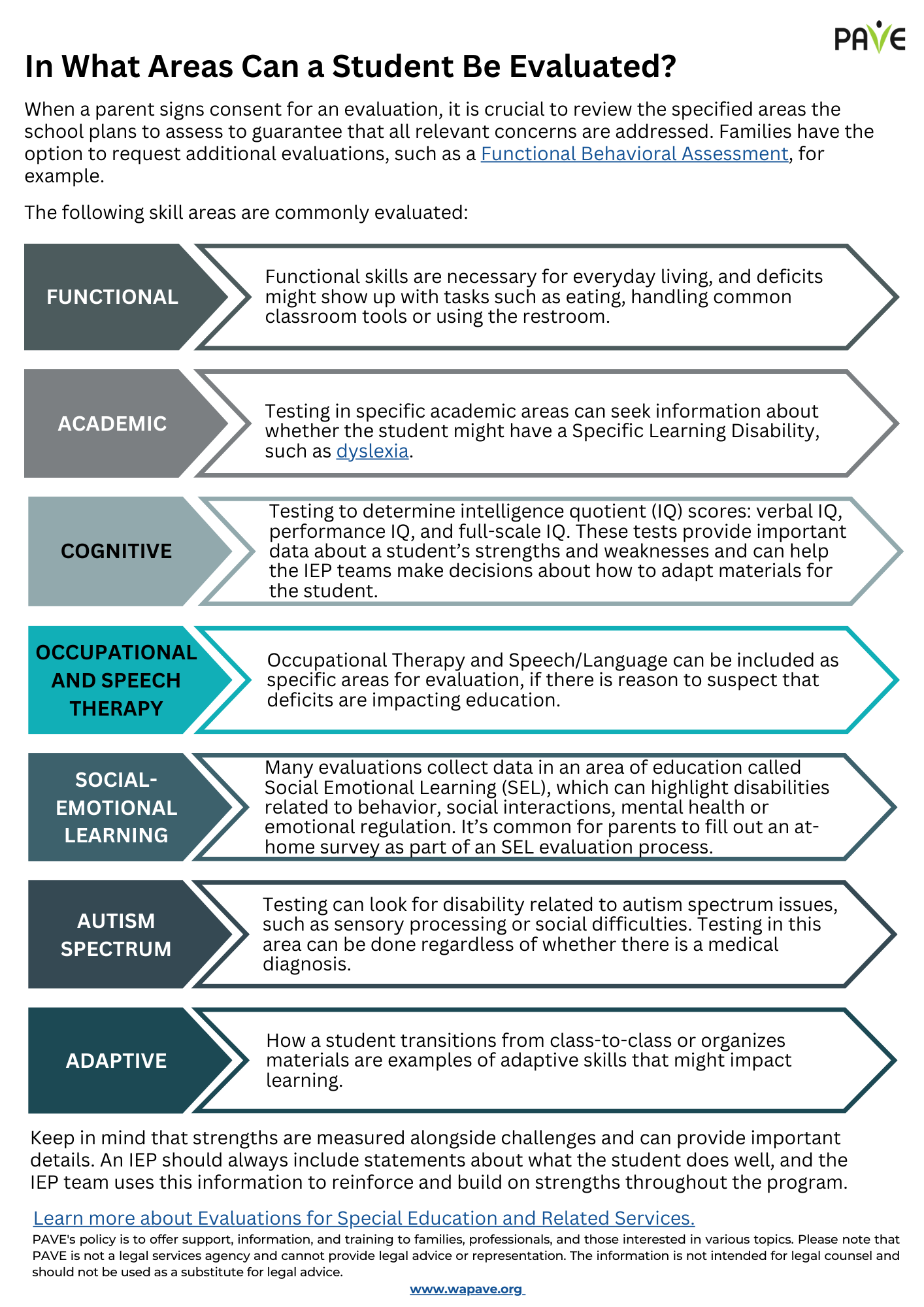

- Appropriate Evaluation: The IDEA requires schools to take a closer look at students with suspected disabilities. That part of the law is called the Child Find mandate. There are rules about how quickly those evaluations get done. The results provide information that the school and parents use to make decisions about how the student’s education can be improved.

- Individualized Education Program (IEP): The IEP is an active program, not a stack of papers. The document that describes a student’s special education program is carefully written and is reviewed at least once a year by a team. This team includes school staff and parents/guardians and the student, when appropriate. Learning in school isn’t just academic subjects. Schools also help students learn social and emotional skills and general life skills. Every student has access to a High School and Beyond Plan by age 12 or 13. By age 16, an IEP includes a transition plan for life beyond high school. This helps the student make a successful transition into adulthood and is the primary goal of the IEP.

- Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): The IDEA says that students should be in class with non-disabled classmates “to the maximum extent appropriate.” That means that regular classrooms and school spaces are first choice as the “least restrictive” places. If the school has provided extra help in the classroom but the special education student still struggles to be successful, then the IEP team considers other options, such as a structured learning classroom. The school explains placement and LRE in writing on the IEP document.

- Parent and Student Participation: The IDEA makes it clear that parents or legal guardians are equal partners with school staff in making decisions about their student’s education. When the student turns 18, educational decision making is given to the student. The school does its best to bring parents and students into the meetings, and there are specific rules about how the school provides written records and meeting notices.

- Procedural Safeguards: The school provides parents with a written copy of their rights at referral and yearly thereafter. Parents may receive procedural safeguards any time they request them. They may also receive procedural safeguards the first time they file a citizen’s request in a school year or when they file for due process. Procedural safeguards are offered when a decision is made to remove a student for more than 10 days in a school year as part of a disciplinary action. When parents and schools disagree, these rights describe the actions that a parent can take informally or formally.

Ready, set, go! 5 steps for parents to participate in the IEP process

Understanding the laws and principles of special education can help parents get ready to dive into the details of how to participate on IEP teams. Getting organized with school work, contacts, calendar details and concerns and questions will help. Here’s the basic 5-step process:

- Schedule

Evaluation is the testing that a school completes to determine if a student meets the requirements for an IEP. A teacher, administrator or parent can refer a student for an educational evaluation. If the student has never had an IEP and the parent is making the request, here are a few tips: Make the request in writing, and know your rights if the school’s answer is no. PAVE provides a sample letter that anyone can use. You can request information and help at wapave.org

Once testing is complete, the school schedules a meeting to discuss the results and whether a team will move forward in developing an IEP. Parents get a written invitation to the meeting. If the date and time don’t work, keep in mind that parents are required members of the IEP team. The school and family agree on a time, and schools document efforts to include parents at all IEP team meetings. You can ask ahead for the agenda to make sure there’s going to be enough time for the topics being discussed.

The school’s invitation lists who’s going to be there. The team could be very large or very small depending on the needs of the student and the professionals involved. Team members include:

- A parent or legal guardian

- A District Representative. A school administrator can fill this role, so this person might be a staff member from the district special services office, a principal, a dean or a building administrator. This person needs to know district policies and should have some power to make decisions and implement team recommendations.

- Experts to explain the testing results. This could be a school psychologist or a specialist such as a physical therapist, occupational therapist, Applied Behavior Analyst (ABA), a nurse, etc.

- Any individuals with knowledge or expertise invited by the school, the student or family. Therapists, counselors, extended family and friends sometimes attend.

- The student. Self-advocacy is important at all ages, but youth making after-high-school plans are especially encouraged to attend, participate or even lead their own meetings. Many parents bring out photographs of their student to place on the table during the discussion. Don’t be afraid to get creative to make sure that the “I” isn’t left out of IEP!

If your student already has an IEP, a re-evaluation occurs at least once every three years unless the team decides differently. A parent can ask for a re-evaluation for different reasons. Usually, a re-evaluation will not occur more than once a year.

- Prepare

Confirm the time and location for the meeting and read the attendance list. If a key member of the team is going to miss the meeting, you will have to sign consent to excuse that person. Ask to reschedule if you aren’t okay with that person being gone.

You can ask for a copy of the evaluation results or a draft copy of the IEP before the meeting to help you get ready. You can collect letters or important documents from medical professionals or other providers to help you explain something that’s concerning you. You may write a short list of questions, so you don’t forget to ask something important during the meeting. Another option is to make a list of your student’s strengths and talents, to make sure that the school’s program builds on what already works. You can write a letter of concern and ask for it to be attached to the IEP document. Consider inviting someone to come with you, to take notes and help you stay focused.

- Learn

Knowing the technical parts of an IEP will help you understand what’s happening at the meeting. Remember that the IEP is a living program, not a document. The document that gets drafted, revised and agreed upon does the best job that it can to describe the positions and intentions of the IEP team. The document is a reference guide for the real-time programming that a student receives at school each day. The IEP is a work-in-progress, and the document can be changed as many times as needed to get it right and help everyone stay on track.

This list includes the technical elements of an IEP:

- Present Levels of Performance, statements that describe how a student is doing in academics, and can include Social Emotional Learning (SEL) and everyday life skills

- Educational Impact Statement, describing the disability and its impact on learning

- Annual Goals, including academic, social, emotional and functional goals. Goals should be SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timely). The IEP provides a specific way to check on progress.

- Assessments: state testing scores, upcoming testing schedules and accommodations for access to the tests

- Program, Placement, Related Services and Supplementary Aids. Special ways of teaching a student are always included in an IEP. How that instruction and the rest of services get delivered is different in every situation and requires collaboration and creativity.

- Scheduling Details: time, duration and location for all special education programs

- Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): Schools explain how much time a student spends in special settings instead of regular settings with general education students. A chart or “service matrix” on the IEP document shows how much time a student spends in each location. This section also describes how the placement meets the LRE requirement “to the maximum extent appropriate.”

- Extracurriculars and other nonacademic activities and how they are accommodated

- Extended School Year (ESY), if the IEP team believes it is necessary.

- Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP), as needed, based on a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) and recommendations from professionals who work with the student

- Transition Plan (required on an IEP at age 16). This can be key to a young person’s future, and families and students need to participate fully. Sometimes counselors from the Department of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) or another agency interview the student or even come to the IEP meeting to help.

- Age of Majority statement and plan for the transfer of rights to the student unless parents have guardianship when a student is 18

- Attend

At the meeting, each person should be introduced and listed on the sign-in sheet. Schools generally assign a staff member as the IEP case manager, and that person usually organizes the team meeting. Any documents that you see for the first time are draft documents for everyone to work on. Remember that everyone at the table has an equal voice, including you!

Having a photo of a student who isn’t attending in the center of the table might help remind the team to keep conversations student-centered. Parents can help to make sure the focus stays on the needs, goals, strengths and interests of their student.

One key topic for discussion might be about the goals and how they are written. The acronym SMART can help the team make sure goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timely. Ask how the school is going to keep track of progress. Decide as a team how often you would like progress reports.

You may discuss placement–where the school day will happen. Families and schools talk about how much time a student is spending in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): Remember that LRE is one of the IDEA’s primary principles. Your opinion in this important conversation about inclusion matters! If your student is not participating with non-disabled peers in academic or extracurricular areas, ask for the reasons in writing.

At the meeting, behavior gets talked about if it’s getting in the way of a student’s ability to learn in school. You can request a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) so the IEP team can develop a Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP) to support the student. The U.S. Office of Special Education Programs has a document called a Dear Colleague Letter that describes the school’s obligations to provide behavior supports when they are needed. That document includes this statement:

“Parents may want to request an IEP team meeting following disciplinary removal or changes in the student’s behavior that impede the student’s learning or that of others, as these likely indicate that the IEP may not be properly addressing the student’s behavioral needs or is not being properly implemented.”

Specific goals for Social Emotional Learning and self-regulation strategies may be needed for appropriate and meaningful access to education. For more ideas, read PAVE’s article series about Social Emotional Learning.

Here’s a list of other topics you may want to consider:

- Modifications your student may need in class or for fire drills, lunch or recess support, walking to/from classes, etc.

- Accommodations your student will need in class or for testing, such as earphones or a specific seat

- Long-term goals: An IEP must include transition goals by age 16, and all Washington schools start Life After High School planning in middle school.

- Extended time over breaks in the school year: Consider how your student might have a pattern of losing and regaining skills or information over extended breaks from school. You also might want to consider if your student is showing signs of emerging skills that potentially could be lost if an extended break from school happens.

Writing down how you plan to communicate with the school can help you participate in the IEP process. Your plan can be written into the IEP during your meeting. This is an individual education program and the team can agree on what is needed for everyone to work together for success. Here are a few ideas for ongoing communication with the school:

- A journal that your student carries home in a backpack

- A regular email report from the Special Education teacher

- A scheduled phone call with the school

- A progress report with a specific sharing plan decided by the team

- Get creative to make a plan that works for the whole team!

During your meeting, ask questions if you don’t understand something. If it is said in the meeting, it can also be put into writing. For example: “The district doesn’t have the funding to offer that.” You can choose to respond, “Please put that in writing.” Any decisions that impact your student’s education or changes to your student’s IEP must be written down in a form called the “Prior Written Notice.” It is like a thank-you note sent after a party. The note states what happened, why it happened and who participated in the event.

5. Follow up

Your meeting may resolve your concerns. If it doesn’t, consider adding notes to the signature page. You can ask for a follow-up meeting or write a letter to be attached to the IEP document. Make sure to follow through with whatever communication plan the team agreed to. The IEP team reviews the program at least once a year but can meet and change the program more often, if needed.

This article began with a brief history of special education law. Parents have played an important role in that history, and they continue to impact the way that special education is provided in the schools. A recent court case that started in Colorado went all the way to the Supreme Court. That case, referred to as Endrew F, raised some standards related to the IEP. PAVE published an article on Endrew F that includes resource links and tips for using language from that court ruling to help in the IEP process.

If all of this sounds a little overwhelming, you can break the work into steps. Figure out the best way to help your family stay organized with paperwork and information. Choose a calendar system that helps you track appointments and deadlines. Collect and mark the dates for major school events, such as back-to-school night and parent-teacher conferences.

You can choose to print this article and highlight the sections you want to remember. Tuck the pages into your notebook or file folder, with the most recent copy of the IEP.

Talking about the upcoming year with your student can help to reduce worries. Talk about new activities, classmates and things that will be the same or familiar. Find out if your school has an open house, and plan to attend. At your visit, talk about the school with your student. What do they like or not like? What’s new or different? What questions do they have? Take pictures during your tour, and you can review them in the days right before school starts.

Try to meet with your student’s teachers and other school helpers, including therapists or even the bus driver, if possible. Helping your student to establish relationships early can ease worries and help the school team know what makes your student unique and awesome. Share a simple “quick reference” version of the IEP or Behavior Plan, if available. You can also write your own simple list of suggestions for success.

From all of us at PAVE, we wish you a happy and successful school year!

Resources for more information:

Office of the Superintendent for Public Instruction (OSPI) Special Education Resource Library

Open Doors for Multicultural Families: Resources

Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR/Parent Center Hub)

Wrightslaw: Tips for Using the IDEA to improve your student’s IEP

Regulations governing the development and content of an IEP are contained in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, Public Law 108-446), and in the Washington Administrative Code (WAC 392-172A).