Looking to the future can feel exciting, hopeful, confusing, overwhelming—or all emotions at once. For families supporting a young person with a disability, it’s never too soon to begin planning to ensure a smooth process from the teen years toward whatever happens next. This toolkit supports families as they organize this multiyear project.

Presenting our newest resource – the Planning My Path Practical Tips and Tools for Future Planning. This toolkit encompasses a collection of our informative articles, complemented by easy to understand timeline charts to provide you with a solid foundation as you navigate through this crucial transition period. Taking some time to look through it may answer some questions that pop up as you get closer to your high school graduation.

Learn the Words

A good place to begin is a Glossary of Key Terms for Life After High School Planning, which provides vocabulary building and an overview of topics relevant to this important phase of life.

Earning a Diploma

To earn a high-school diploma in Washington State, students must:

OSPI provides a two-page summary of graduation requirements to support families and students. Included is this statement: “Students who receive special education services under an Individualized Education Program (IEP), also have an IEP Transition Plan, which begins by the school year when a student turns 16 or sooner. The HSBP is required to align with their IEP Transition Plan to ensure a robust planning process toward post-high school goals.”

Various state agencies collaborated to provide a guidebook: Guidelines for Aligning High School & Beyond Plans (HSBP) and IEP Transition Plans.

The state’s 2019 legislature changed graduation requirements (HB 1599). Students may earn a Certificate of Academic Achievement (CAA) or a Certificate of Individual Achievement (CIA) to graduate. How a student earns a CIA is determined by their IEP team.

Students with disabilities seeking a diploma through General Educational Development (GED) testing may be eligible for testing accommodations. A website called passged.com lists a variety of disability conditions that might make a person eligible for testing supports.

Commencement Access

Regardless of when a diploma is earned, a student can participate in Commencement at the end of a traditional senior year, with peers, under a Washington provision called Kevin’s Law. Families may want to plan well in advance with school staff to consider how senior year events are accessible to youth with disabilities.

The Big Picture

The right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) includes the right to school-based services that prepare a young person with a disability for adult life.

Here are links to a training video, infographic, and article:

Various state agencies collaborated to provide a downloadable guidebook: Guidelines for Aligning High School & Beyond Plans (HSBP) and IEP Transition Plans. Included are career-planning tools and linkages to current information about Graduation Pathways, which changed in 2019 when the Washington State Legislature passed House Bill (HB) 1599.

Student Self-Advocacy

As they move toward adulthood, many students benefit from opportunities to practice skills of self-advocacy and self-determination. One way to foster those skills is to encourage youth to get more involved in their own Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). To support that, PAVE provides this article: Attention Students: Lead your own IEP meetings and take charge of your future. Included is a handout that students might use to contribute to meeting agendas.

The RAISE Center (National Resources for Advocacy, Independence, Self-determination and Employment) provides a blog with transition related news, information, ideas and opinions. Topics in 2020-21 include how to “Be the Best You,” how issues of race and disability intersect with equity, and how “The Disability Agenda Could Bring Unity to A Fragmented Society,” by RAISE Center co-director Josie Badger, who is a person living with disability.

Student Rights after High School

An Individualized Education Program (IEP) ends when a student leaves secondary education. The protections of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 are ongoing throughout the lifespan.

These laws provide for appropriate accommodations in public programs and facilities. To support these disability protections, The IEP accommodations page or a Section 504 Plan can travel with a student into higher education, a vocational program, or work. Often a special services office at an institution for higher learning includes a staff member responsible for ensuring that disability rights are upheld. PAVE provides an article with general information about Section 504 rights that apply to all ages: Section 504: A Plan for Equity, Access and Accommodations.

Universal Design supports everyone

Asking for rights to be upheld is not asking for special favors. A person living with disability, Kyann Flint, wrote an article for PAVE to describe how Universal Design supports inclusion. Her article can provide inspiration for young people looking for examples of what is possible, now as ever: COVID-19 and Disability: Access to Work has Changed.

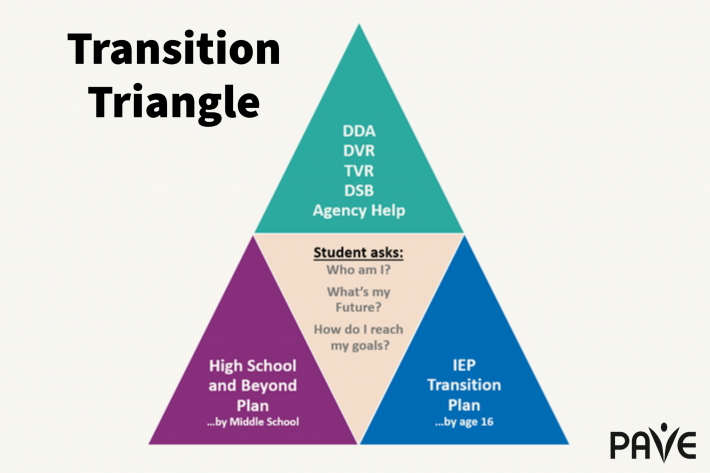

Agencies that can help

Washington State’s Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) provides services for high-school students engaged in transition planning as well as adults seeking employment. PAVE provides an article that describes Pre-Employment Transition Services (Pre-ETS) and more: Ready for Work: Vocational Rehabilitation Provides Guidance and Tools.

DVR’s website includes a section with information about Tribal Vocational Rehabilitation (TVR), which is available for people with tribal affiliations in some areas of the state. Each TVR program operates independently. Note that some TVR programs list service areas by county but that sovereign lands are not bound by county lines. Contact each agency for complete information about program access, service area, and eligibility.

Services for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing are provided by Washington’s Center for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Youth (CDHY), which was formerly called the Center for Childhood Deafness and Hearing Loss (CDHL). This statewide resource supports all deaf and hard of hearing students in Washington, regardless of where they live or attend school.

Services for individuals who are blind or living with low vision are provided by Washington’s Department of Services for the Blind (DSB). Youth services, Pre-Employment Transition Services (Pre-ETS), Vocational Rehabilitation, Business Enterprise Program, and mobility and other independent-living skills are served by DSB.

The Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) also has a variety of school-to-work and waiver programs that support youth. PAVE provides a video to support families through the DDA eligibility process. An article provides further detail: How to Prepare for a DDA Assessment.

Not all youth with disabilities are able to access employment-related services through DVR, TVR, DSB, or DDA. A limited additional option is Goodwill, which provides access to a virtual learning library. Students can take classes at their own pace for skills development. Employment skills, workplace readiness, interviewing skills and more are part of the training materials. To request further information, call 253-573-6507, or send an email to: library@goodwillwa.org.

Graduation’s over: Why is school calling?

Schools are responsible to track the outcomes of their special education services. Here’s an article to help families get ready to talk about how things are going: The School Might Call to Ask About a Young Adult’s Experience After High School: Here’s Help to Prepare

Benefits Planning

A consideration for many families of youth with disabilities is whether lifelong benefits are needed. Applying for social security just past the young person’s 18th birthday creates a pathway toward a cash benefit and enables the young person to access Medicaid (public health insurance) and various programs that depend on Medicaid eligibility.

The Washington Initiative for Supported Employment (gowise.org) provides benefit planning information and resources through a program called BenefitU.

When a person 18 or older has a disability, family members may want to stay involved in helping them make decisions. Supported Decision Making (SDM) is the formal name for one legal option. Washington law (Chapter 11.130 in the Revised Code of Washington) includes Supported Decision Making as an option under the Uniform Guardianship, Conservatorship, and Other Protective Arrangements Act. The law changed in 2020 when the state passed Senate Bill 6287. The changes took effect Jan. 1, 2022. PAVE’s article about Supported Decision Making has more information about this and other options for families to support an adult with a disability.