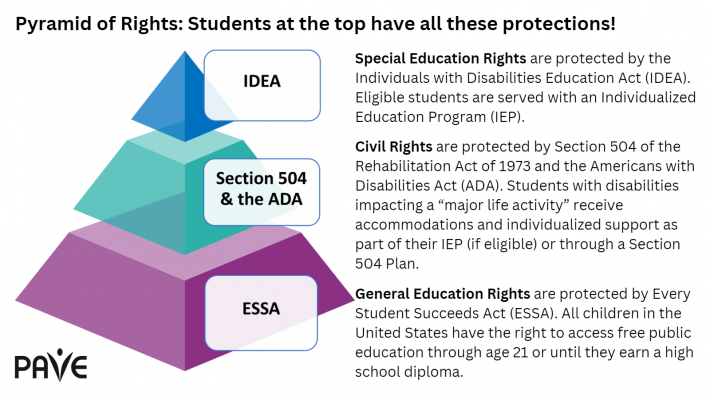

A student with a disability is protected by multiple federal laws. One of these laws is the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This law is enforced by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. Section 504 is part of the Rehabilitation Act and it helps protect students from being treated unfairly because of their disability.

To uphold a student’s civil rights under Section 504, schools provide accommodations and support to ensure that a student with a disability has what they need to access the opportunities provided to all students. Making sure all students have the same opportunities is called equity, and it’s something schools must do. Students with disabilities are protected in all parts of school life, like classes, sports, clubs, and events.

A Brief Overview

- Section 504 is part of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which is upheld by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

- Section 504 prohibits discrimination based on disability in any program or activity that receives federal funding. All Washington state public schools must comply with this federal law.

- Every student with a disability is protected from discrimination under this law, including each student with a 504 Plan and each student with an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

- Eligibility for Section 504 support at school is determined through evaluation. Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) provides fact sheets in multiple languages that describe the evaluation process and state requirements.

- A mitigating measure is a coping strategy used by individuals with disabilities to reduce the effects of a disability, but these measures cannot be considered when determining if a student has a substantially limiting impairment.

- Dispute resolution options are outlined in the Section 504 Notice of Parent Rights, downloadable in multiple languages on the OSPI website.

Introduction

Every student with a disability is protected from discrimination under this law, including each student with a 504 Plan and each student with an Individualized Education Program (IEP). Section 504 protects a person with disabilities throughout life and covers individuals in any public facility or program. A person can have a 504 Plan to support them in a vocational program, higher education, or in any location or service that receives federal funds.

All people with recognized disabilities also have protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Within a school, business, or other organization, the person responsible for upholding civil rights under these two laws might hold a title such as Section 504/ADA Compliance Officer. If you have concerns about civil rights being followed in any group, ask to speak with the person responsible for Section 504/ADA compliance. You may also ask for policies, practices, and complaint options in writing.

Hidden disabilities, or those that are not readily apparent to others, are also recognized disabilities protected by Section 504 and the ADA. Hidden disabilities may include but are not limited to learning disabilities, psychological disabilities, and episodic conditions, such as epilepsy or allergies.

Defining “Disability” under Section 504

Section 504 does not specifically name disability conditions and life impacts in order to capture known and unknown conditions that could affect a person’s life in unique ways. In school, determination is made through evaluations that ask these questions:

- Does the student have an impairment?

- Does the impairment substantially limit one or more major life activities?

Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) provides fact sheets about Section 504 in multiple languages that describe the evaluation process and state requirements. Included in the fact sheets is this information about what Section 504 means for students:

“Major life activities are activities that are important to most people’s daily lives. Caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning, working, eating, sleeping, standing, bending, reading, concentrating, thinking, and communicating are some examples of major life activities.

“Major life activities also include major bodily functions, such as functions of the digestive, bowel, bladder, brain, circulatory, reproductive, neurological, or respiratory systems.

“Substantially limits should also be interpreted broadly. A student’s impairment does not need to prevent, or severely or significantly restrict, a major life activity to be substantially limiting.”

FAPE rights under Section 504

The right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) is protected by Section 504 and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The most common way schools protect Section 504 FAPE rights is through accommodations. A student might have specifically designed help to accomplish their schoolwork, manage their emotions, use school equipment, or something else. The sky is the limit, and Section 504 is intentionally broad to capture a huge range of possible disability conditions that require vastly different types and levels of support.

Here are two specific topic areas to consider when a student is protected by Section 504:

- FAPE rights include the right to be supported against bullying.

- FAPE rights protect students against unfair treatment in student discipline.

Medical Diagnosis

A school cannot require a parent to provide a medical diagnosis to evaluate a student. However, a diagnosis can provide helpful information. The school could request a medical evaluation, at no cost to the parent, if medical information would support decision-making.

Note that a medical diagnosis does not automatically mean a student needs a 504 Plan. Doctors cannot prescribe a 504 plan—only the 504 team can make that decision. However, the 504 team must consider all information provided as part of its evaluation process.

Evaluation and Eligibility Determination

Eligibility for school-based services is determined through evaluation. Federal law that protects students in special education process is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

IDEA includes Child Find protections that require schools to evaluate a student if there is a reasonable suspicion that disability is impacting educational access. A student is evaluated in all areas of suspected disability to determine eligibility for services. If the student is found eligible, the evaluation provides key information about service needs.

Parents or guardians, teachers, district personnel, and others with information about the student can refer the student for evaluation for special education by completing the OSPI Referral for Special Education Evaluation form (direct download), which is available on the OSPI website.

After the student is evaluated, the 504 team will discuss the results of the evaluation with the parent or guardian. Depending on the results, the student will be found:

- Eligible for Section 504 protections but not an IEP. Data from the evaluation is used to build a Section 504 Plan for supporting the student with individualized accommodations and other needed supports.

- Eligible for an IEP. The special education program includes goals that track progress toward learning in areas of specially designed instruction (SDI). Accommodations and supports that are protected by Section 504 are built into the IEP.

- The school determines that the student does not have a disability, or that a disability does not substantially limit educational activities. The student will not receive school-based services through an individualized plan or program.

Evaluations must disregard mitigating measures

A mitigating measure is a coping strategy that a person with a disability uses to eliminate or reduce the effects of a disability. For example, a person who is deaf might read lips or a person with dyslexia may read using audible books. Because a person has adapted to their disability does not mean they give up the right to appropriate, individualized support. In its guidance, OSPI states: “Mitigating measures cannot be considered when evaluating whether or not a student has a substantially limiting impairment.”

A school also cannot determine a student ineligible based on a condition that comes and goes. Students with health conditions that are episodic or fluctuate, like sickle cell disease, Tourette’s Syndrome, or bipolar disorder, might qualify for Section 504 protections, even if they appear unaffected on some school days. According to OSPI, “An impairment that is episodic or in remission remains a disability if, when in an active phase, this impairment substantially limits a major life activity.”

Section 504 Dispute Resolution Options

When navigating disagreements with a school’s decisions, it’s important for parents to know their rights and the resources available to them. The Section 504 Notice of Parent Rights is the procedural safeguards for student and parent rights under Section 504. It is available for download in multiple languages from OSPI. This document outlines the various options for resolving disputes between families and school districts. Understanding these rights can empower parents to advocate effectively for their children.

If they disagree with the methods, findings, or conclusions from a district evaluation, families have the right to request an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE) at school district expense. The district is required to provide information on where to obtain an IEE and the guidelines to follow. Should the district refuse the IEE, they have 15 calendar days to either initiate a due process hearing or agree to fund the IEE. PAVE offers a downloadable sample letter for requesting an Independent Educational Evaluation. Being aware of these steps ensures that parents can take timely action to support their child’s educational needs.

Anyone can file a complaint about discrimination involving students with disabilities in a Washington public school, which is prohibited by Washington law (RCW 28A.642.010). A civil rights complaint can be filed at the local, state, or federal level. Here are resources related to those three options:

- OSPI maintains a list of school officials responsible for upholding student civil rights to resolve issues at the local level. Families can reach out to those personnel to request a complaint form for filing a civil rights complaint within their district.

- OSPI’s Complaints and Concerns About Discrimination page contains direct links to step-by-step instructions for filing a civil rights complaint with the state Equity and Civil Rights Office, or the Human Rights Commission.

- On the federal level, the U.S. Department of Education provides guidance about filing a federal complaint. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is another option for dispute resolution related to civil rights.