Every student deserves a strong start to the school year. For families of children with disabilities, preparing for school includes reviewing the Individualized Education Program (IEP). The IEP is a legal document and a living plan that outlines the supports and services a student needs to access their education. Families play a key role in shaping the IEP and making sure it works for their child.

A Brief Overview

- The start of a new school year is a great time for families to revisit or begin the IEP process to support their student’s learning.

- If a student doesn’t yet have an IEP, requesting an evaluation is the first step to determine eligibility for special education services.

- Review the IEP before school starts to prepare questions and suggestions for the team.

- Talk with your student about what to expect to reduce anxiety and build confidence.

- Learn about the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) to understand your rights and responsibilities in the IEP process.

- Communicate regularly with the IEP team to monitor progress and adjust plans as needed.

- Gather documents, write questions, and invite support to prepare for IEP meetings.

- Follow up after meetings to confirm next steps and maintain communication.

- Take small, manageable steps to stay involved and support your student’s success.

Introduction

The beginning of a new school year is the perfect time to revisit your student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). Whether your child already has an IEP or you’re just starting to explore the special education process, this season offers a fresh opportunity to reflect, plan, and engage.

As you and your student get ready for school, the most important thing is the “I” in IEP. The “I” is for “Individualized”. A thoughtful IEP highlights abilities and helps your student access the supports needed to learn. It helps ensure they receive the support necessary to learn, grow, and make meaningful progress—not just in school, but in life beyond graduation.

IEPs are built by teams, and families are essential members. When parents and students understand the process and actively participate, they help shape a plan that truly works.

What to do before the first day

If your student doesn’t have an IEP and you wonder whether a disability might be affecting their learning, now is a great time to explore the special education process. Understanding how evaluations work is the first step. If you’re unsure whether your child needs one, check out our article on How to Request an Evaluation, which explains how to get started.

Before the school year begins, review the IEP to prepare questions and suggestions for the team. PAVE recommends using their Steps to Read, Understand, and Develop an Initial IEP worksheet to guide this process.

After reviewing your student’s IEP or beginning the process to request one, the next step is ensuring your child is properly enrolled in school. Enrollment procedures vary by district, but they typically include submitting documentation, verifying residency, and understanding school assignment policies. For a clear overview of how and when to enroll your student, read this PAVE article: Starting School: When and How to Enroll a Student in School.

To help ease anxiety and build excitement, talk with your child about what to expect. Discuss new activities, classmates, and what will feel familiar. If your school offers an open house, plan to attend together. During your visit, take pictures and ask your child what they notice or wonder about. You can review the photos later to help them feel more prepared. PAVE’s article, Tips to Help Parents Plan for the Upcoming School Year, provides actionable strategies for easing anxiety, fostering independence, and creating a positive school experience.

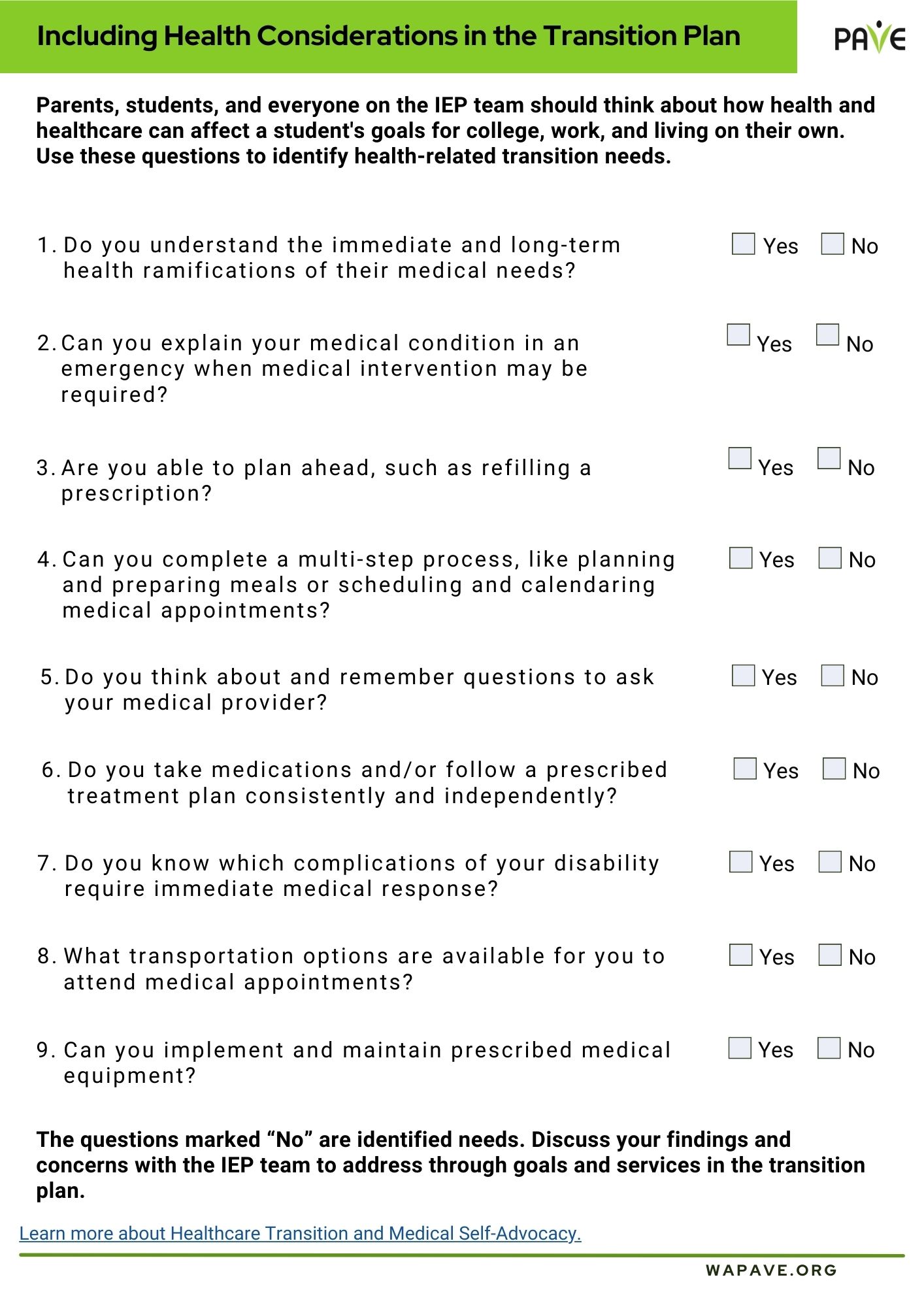

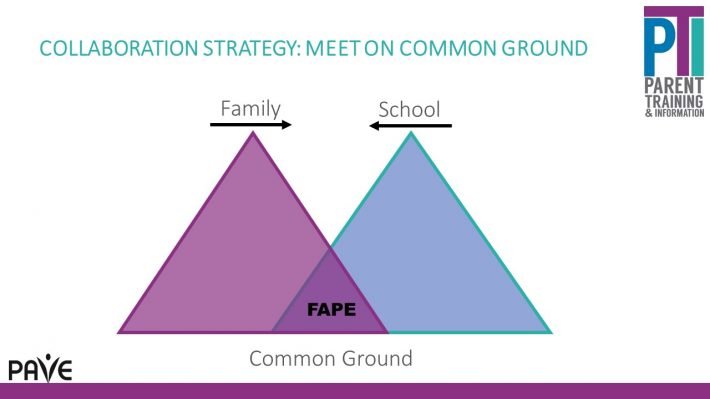

What parents need to know about FAPE

At the heart of special education is the right to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), guaranteed by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). FAPE means that students with disabilities are entitled to an education tailored to their individual needs—not a one-size-fits-all program. This is what makes IDEA unique: it ensures that every eligible student receives services designed specifically for them through an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

To qualify for an IEP, a student must go through an evaluation process to determine if a disability is impacting their education. If the student meets criteria under IDEA, they become eligible for special education services. These services are not about placing a student in a specific classroom—they’re about providing the right support, wherever the student learns. As you review your child’s IEP or prepare for meetings, ask: Is this plan appropriate and suitable for my child’s unique abilities and needs?

IDEA includes six important principles

The IDEA, updated several times since 1990, outlines legal rights for students with disabilities and their families. This PAVE article, Special Education Blueprint: The Six Principles of IDEA, explores the core principles, including: Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), Appropriate Evaluation, Individualized Education Program (IEP), Least Restrictive Environment (LRE), Parent and Student Participation, and Procedural Safeguards.

Effective communication is key to student success

Understanding legal rights is just the beginning—clear, consistent communication with the IEP team is one of the most effective ways to ensure your student’s plan leads to meaningful progress. Consider creating a communication plan with your child’s teachers or case manager. This might include weekly emails, a journal sent home in the backpack, scheduled phone calls, or progress reports. Be sure to have this plan written into the IEP or included in the Prior Written Notice (PWN) so everyone stays on the same page.

Writing down how you’d like to stay in touch helps the team understand what works best for your family. Get creative—what matters most is that the plan supports clear, consistent communication for the whole team. Here are a few ideas for ongoing communication with the school:

- A journal that your student carries home in a backpack

- A regular email report from the Special Education teacher

- A scheduled phone call with the school

- A progress report with a specific sharing plan decided by the team

- Get creative to make a plan that works for the whole team!

Keep a log of communication with the school district and educational service providers. PAVE provides a downloadable Communication Log to help you track emails, phone calls, and texts.

Ready, set, go! 5 steps for parents to participate in the IEP process

Understanding the laws and principles of special education can help parents get ready to dive into the details of how to participate on IEP teams. Getting organized with schoolwork, contacts, calendar details, and concerns and questions will help.

This 5-step process is downloadable as an infographic.

Download the IEP Essentials in 5 Steps in:

English | Chinese (Simplified) 中文 (Zhōngwén) | Korean 한국어 (Hangugeo) | Russian Русский (Russkiy) | Somali Soomaali | Spanish Español | Tagalog | Ukrainian українська | Vietnamese Tiếng Việt

1. Schedule

Parents or guardians should receive a written invitation to the meeting. The school and family agree on a date and time, and the school documents efforts to include families at all IEP team meetings. If the proposed time doesn’t work, remember that parents are required members of the team—you can request a different time that works better for you.

Ask beforehand for the agenda and a list of who will attend. This helps ensure there’s enough time to fully address the topics being discussed. If a key team member can’t attend the meeting, you have the option to either provide written consent to excuse their absence or request to reschedule if their participation is important to you. For a list of suggested attendees and a downloadable form to save contact information, PAVE provides a Who’s Who on the IEP Team.

If your student already has an IEP, a re-evaluation occurs at least once every three years unless the team decides differently. A parent can ask for a re-evaluation for sooner if needed, though typically a re-evaluation will not occur more than once a year.

2. Prepare

You can ask for a copy of the evaluation results or a draft IEP before the meeting to help you prepare. It’s a good idea to gather letters or documents from medical providers or specialists that support your concerns. Writing down a few questions ahead of time can help you remember what you want to ask. You might also make a list of your student’s strengths and talents—this helps the team build on what’s already working. If you have specific concerns, you can write a letter and ask for it to be included in the IEP. Some families invite a support person to attend the meeting, someone who can take notes, help you stay focused, and offer encouragement.

3. Learn

Knowing the technical parts of an IEP will help you understand what’s happening at the meeting. The IEP is a living program—not just a document—and it can be updated anytime to better meet your child’s needs. The IEP is a work-in-progress, and the document can be changed as many times as needed to get it right and help everyone stay on track.

Familiarize yourself with the components of an IEP:

- Present levels of performance

- Educational impact statement

- SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Timely)

- Services, supports, and placement

- LRE details

- Transition planning (starting by age 16)

- Behavior supports, if needed

- Specially designed Instruction

4. Attend

At the meeting, each person should be introduced and listed on the sign-in sheet. Schools generally assign a staff member as the IEP case manager, and that person usually organizes the team meeting. Any documents that you see for the first time are draft documents for everyone to work on.

Be present and free of distractions so you can fully participate. Ask questions, share your perspective, and help keep the focus on your child’s needs and goals. If your child isn’t attending, placing a photo of them on the table may remind the team to keep conversations student-centered.

Everyone at the table has an equal voice, including you!

5. Follow up

After the meeting, follow through with the agreed communication plan. Make sure that everyone’s contact information is current and that you know how and when updates will be shared. If you still have concerns after the meeting, request a follow-up meeting or submit additional notes.

Stay organized with calendars, contact lists, and copies of important documents. Talk with your child about the upcoming year to ease anxiety and build excitement!

Tips for a smooth school year

As the school year begins, it’s important to think proactively about how to support your child’s learning and development. Establishing routines, setting goals, and building relationships with school staff can make a big difference.

If all of this sounds a little overwhelming, break the work into steps. Determine the best way to help your family stay organized with paperwork and information. Choose a calendar system that helps you track appointments and school events, such as back-to-school night or parent-teacher conferences.

Help your child’s team understand what works best for your student and share their strengths with a one-pager or a letter of introduction. PAVE provides a one-pager template, What You Need To Know About My Child, and a sample letter of introduction, Sample Letter to the IEP Team – Today Our Partnership Begins.

Let’s wrap things up!

Getting ready for school can feel like a lot, especially when your child has an IEP. But you don’t have to do everything at once. Take it one step at a time, and remember: you are not alone. This journey includes your child, and you’re walking it together. You are a vital part of your child’s team, and your voice truly matters. When families and schools work as partners, amazing things can happen. So trust yourself, speak up, and share what you know—because no one knows your child better than you. You bring love, insight, and hope to the table.

From all of us at PAVE, we wish you a happy and successful school year!

Learn More

- PAVE – Placement: Deciding Where a Student Spends the School Day: Understand how placement decisions are made and what options may be available for students.

- PAVE – What Parents Need to Know when Disability Impacts Behavior and Discipline at School: Explains how behavior and discipline are handled within special education and what rights families have.

- PAVE – Toolkits Ready for You!: Offers downloadable guides and checklists to help families stay organized and informed throughout the IEP process.

- Office of the Superintendent for Public Instruction (OSPI) Special Education Resource Library: Provides access to Washington State’s official guidance, forms, and tools for navigating special education.