A Brief Overview

- Understanding trauma and providing consistent skill building in Social Emotional Learning (SEL) can improve outcomes in education and elsewhere.

- Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction provides free SEL training materials for educators and families on its website: k12.wa.us.

- Trauma-informed adults can use specific strategies to help children understand their emotions, describe what is happening, and make skillful decisions about what to do next. Read on for ideas about what works.

- Family caregivers can ask school staff what they know about trauma-informed instruction and how their own knowledge and training in SEL informs their strategies when teaching a class or a specific student.

Full Article

“Being at school in a traumatized state is like playing chess in a hurricane.” This statement, from Mount Vernon high-school teacher Kenneth Fox, provides a vivid reminder that learning is not just about academics. Effective social interactions and emotional regulation are critical lifelong skills.

Fox’s quote is highlighted in a free guidebook offered by Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI): The Heart of Learning and Teaching: Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success.

OSPI also provides SEL learning activities for families and educators. OSPI addresses family caregivers directly to describe the resource: “SEL provides skills to do things like cope with feelings, set goals, and get along with others. You can help your kids work on these skills at home and have some fun along the way. It’s important to discuss the SEL skill that will be addressed in the activity (e.g., kindness, empathy, self-exploration, decision-making) to make the activity more focused and targeted on that skill.”

Statewide SEL initiatives have been boosted by a sequence of legislative actions. The 2015 legislature directed OSPI to convene an SEL Benchmarks workgroup, and subsequent bills supported development of SEL learning standards. Information about the history of the work is available through OSPI’s website: k12.wa.us. PAVE provides an article with an overview of the SEL standards and more: State Standards Guide Social Emotional Learning for all Ages and Abilities

Trauma-Informed instruction starts with SEL support for educators

Movement toward Social Emotional Learning (SEL) has grown from knowledge that trauma profoundly impacts educational outcomes. In the 1990s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released findings about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which leave children less resilient and less able to manage their behavior.

Dr. Vincent Felitti, then CDC chief of preventive medicine, boldly proclaimed childhood trauma a national health crisis. The report led to development of an ACEs survey, which scores a person’s likelihood of suffering lifelong physical and mental health impairments resulting from trauma. An ACEs score of 4, the study found, makes a child 32 times more likely to have behavior problems at school.

As data from the ACEs study began to circulate, educators sought new ways to help children cope at school. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) formed in 1994 with the goal of establishing evidence based SEL as an essential part of education.

In 1997, CASEL and the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) partnered on Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators, with strategies for SEL programming from preschool through grade 12. “This was the first book of its kind,” CASEL states, “and it laid the foundation for the country to begin addressing the ‘missing piece’ in education.”

CASEL helped fund a February 2017 report about SEL training for teachers. To Reach the Students, Teach the Teachers examines SEL as an aspect of teacher certification and concludes that higher education has more work to do to make sure teachers are prepared:

“The implications for good teaching, and for the implementation of SEL in particular, make it clear there’s serious work to be done. If teachers are not aware of their own social and emotional development and are not taught effective instructional practices for SEL, they are less likely to educate students who thrive in school, careers, and life.”

Toxic stress results from untreated trauma

A 2016 film, Resilience, by KPJR Films, looks at an aspect of trauma called “toxic stress,” which results from exposure to strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, violence, economic hardship, etc.

According to the film’s website, “Toxic stress can trigger hormones that wreak havoc on the brains and bodies of children, putting them at a greater risk for disease, homelessness, prison time, and early death. While the broader impacts of poverty worsen the risk, no segment of society is immune.

“Resilience, however, also chronicles the dawn of a movement that is determined to fight back. Trailblazers in pediatrics, education, and social welfare are using cutting-edge science and field-tested therapies to protect children from the insidious effects of toxic stress—and the dark legacy of a childhood that no child would choose.”

Tip: Ask about a teacher’s experience and training in SEL

Family caregivers can ask school staff what they know about trauma-informed instruction and how their own knowledge and training in SEL informs their strategies when teaching a class or a specific student.

Collaborate with the teacher to consider whether an approach at home might match what’s being used in the educational setting. Common responses and phrases will reinforce a child’s emerging SEL skills and provide predictability, which is evidence-based to comfort and calm children.

What does trauma-informed instruction mean?

Generally, trauma-informed instructional techniques help children understand their emotions, describe what is happening, and make skillful decisions about what to do next.

An agency called Edutopia provides an article that lists some common misunderstanding about trauma-informed instruction. One is that children with trauma in their past need to be “fixed.”

“Our kids are not broken, but our systems are,” the article by elementary principal Mathew Portell states. “Operating in a trauma-informed way does not fix children; it is aimed at fixing broken and unjust systems and structures that alienate and discard students who are marginalized.”

Portell, whose Nashville, Tenn., school has been spotlighted as a leader in trauma-informed strategies, points out also that staff are not acting as therapists. “Our part in helping students with trauma is focusing on relationships, just as we do with all of our students. The strong, stable, and nurturing relationships that we build with our students and families can serve as a conduit for healing.”

A trauma-informed instructor might use a specific tool to help the child label an episode of dysregulation, such as the Zones of Regulation, which encourage self-observation and emotional awareness. Another good example is the “brain-hand model” described by Dan Siegel, a well-known neurobiologist and author who has helped lead a movement toward science-informed practices. PAVE provides a video demonstrating the technique to avoid “flipping your lid.”

Here’s how to make and use a hand model of the brain:

- Hold up your hand. The base of your open palm represents the brain stem, where basic functions like digestion and breathing are regulated.

- Cross your thumb over your palm. This represents the central brain (amygdala), where emotions process.

- Fold your four fingers down over your thumb. They represent your frontal cortex, where problem-solving and learning happen.

- Imagine something emotional triggers you and begin to flutter or lift your fingers.

- When you “flip your lid,” the fingers pop up all the way while emotions based in the amygdala rule. Problem behaviors may become probable as you try to cope with fight/flight instincts based in the autonomic nervous system.

- Practice even, steady breathing to regulate the nervous system, and slowly settle the fingers back over the thumb.

- As your fingers fold down, consider what the mind feels like when problem-solving is accessible versus how it feels when emotions disrupt clear thinking.

- Consider how this hand model might help you or someone else recognize and manage an emotional moment.

SEL builds resilience and reduces need for discipline

A Washington agency that teaches self-awareness and resiliency is Sound Discipline, a non-profit based in Seattle. Begun by pediatrician Jody McVittie, Sound Discipline trains about 5,000 educators and parents each year, estimating to impact more than 100,000 children annually.

Like similar programs, Sound Discipline describes “problem” behaviors as coping mechanisms. Acting out is a child’s attempt to manage stress or confusing emotions, and stern punishments can re-ignite the trauma, making the behavior worse instead of better.

A principal goal is to train professionals and parents to collaborate with students in problem solving. Helping a student repair damage from a behavior incident, for example, teaches resilience and develops mental agility. “Children don’t want to be inappropriate,” McVittie emphasizes. “They are doing the best they can in the moment.”

Educational outcomes improve dramatically when students can manage themselves socially and emotionally. A measure of the impact is a reduction in suspensions and expulsions. A 2016 report from the Child Mind Institute shows that proactively teaching restorative discipline reduces school suspensions and drop-out rates:

“Restorative Discipline/Justice includes strategies to both prevent children from breaking the rules and intervene after an infraction has occurred. Some elements are focused on reducing the likelihood of student rule breaking (proactive circles where students and teachers talk about their feelings and expectations) and others on intervening afterwards (e.g., restorative conferences where the parties talk about what happened). In all cases the focus is on avoiding punishment for the sake of punishment.”

Trauma toolkits for educators and families

As part of its materials for school staff and families, OSPI provides a handout that focuses on culturally responsive SEL approaches. The handout states, “Culturally responsive practices are intentional in critically examining power and privilege, implicit biases, and institutional racism, which serve as barriers to realizing the full potential of transformative social emotional learning (SEL) practices.”

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN.org) provides articles about evidence-based practices for adults supporting children with a wide range of circumstances. The website includes links specifically for military families, for example, and includes content related to early learning, homeless youth, and for families and educators supporting children with intellectual and developmental disabilities who also have experienced trauma (I/DD Toolkit).

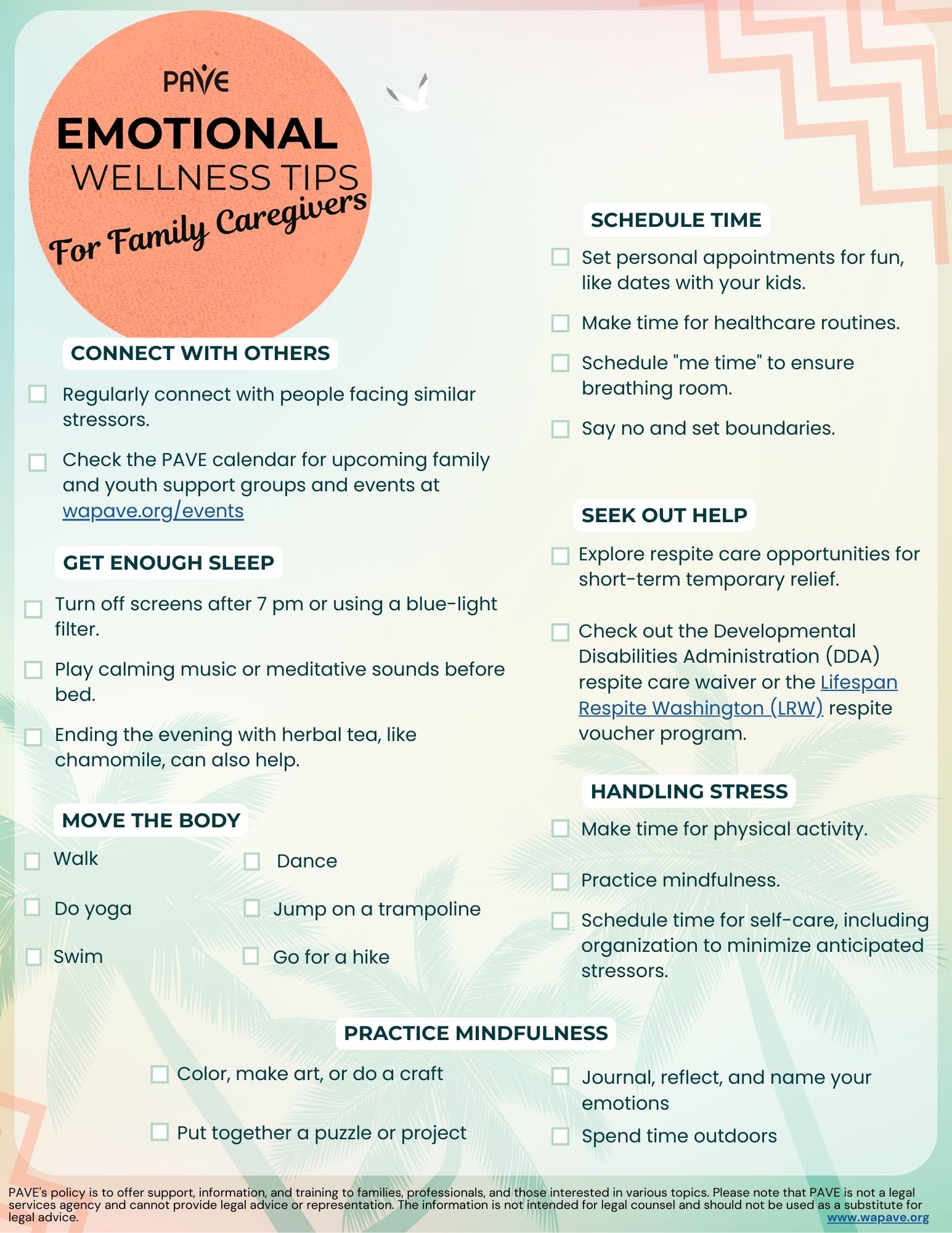

Adults need self-care and their own SEL to support children

Family caregivers play an important role in furthering trauma-informed approaches by learning about and healing their own trauma experiences, applying trauma-informed principles in their parenting and by learning how to talk about these approaches with schools.

According to Lee Collyer, OSPI’s program supervisor for special education and student support, adults may need to consider their own escalation cycles and develop a personal plan for self-control to support children. Collyer helped develop a three-part video training series for parents, especially while children are learning from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. PAVE provides a short article describing the video series, with links to each section: Webinars offer Parent Training to Support Behavior during Continuous Learning.

In Spring 2020, PAVE launched a series of mindfulness videos with short practices for all ages and abilities and an article with self-care strategies: Stay-Home Help: Get Organized, Feel Big Feelings, Breathe.

A Brief Overview

- Understanding trauma and providing consistent skill building in Social Emotional Learning (SEL) can improve outcomes in education and elsewhere.

- Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction provides free SEL training materials for educators and families on its website: k12.wa.us.

- Trauma-informed adults can use specific strategies to help children understand their emotions, describe what is happening, and make skillful decisions about what to do next. Read on for ideas about what works.

- Family caregivers can ask school staff what they know about trauma-informed instruction and how their own knowledge and training in SEL informs their strategies when teaching a class or a specific student.

Full Article

“Being at school in a traumatized state is like playing chess in a hurricane.” This statement, from Mount Vernon high-school teacher Kenneth Fox, provides a vivid reminder that learning is not just about academics. Effective social interactions and emotional regulation are critical lifelong skills.

Fox’s quote is highlighted in a free guidebook offered by Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI): The Heart of Learning and Teaching: Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success.

OSPI also provides SEL learning activities for families and educators. OSPI addresses family caregivers directly to describe the resource: “SEL provides skills to do things like cope with feelings, set goals, and get along with others. You can help your kids work on these skills at home and have some fun along the way. It’s important to discuss the SEL skill that will be addressed in the activity (e.g., kindness, empathy, self-exploration, decision-making) to make the activity more focused and targeted on that skill.”

Statewide SEL initiatives have been boosted by a sequence of legislative actions. The 2015 legislature directed OSPI to convene an SEL Benchmarks workgroup, and subsequent bills supported development of SEL learning standards. Information about the history of the work is available through OSPI’s website: k12.wa.us. PAVE provides an article with an overview of the SEL standards and more: State Standards Guide Social Emotional Learning for all Ages and Abilities

Trauma-Informed instruction starts with SEL support for educators

Movement toward Social Emotional Learning (SEL) has grown from knowledge that trauma profoundly impacts educational outcomes. In the 1990s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released findings about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which leave children less resilient and less able to manage their behavior.

Dr. Vincent Felitti, then CDC chief of preventive medicine, boldly proclaimed childhood trauma a national health crisis. The report led to development of an ACEs survey, which scores a person’s likelihood of suffering lifelong physical and mental health impairments resulting from trauma. An ACEs score of 4, the study found, makes a child 32 times more likely to have behavior problems at school.

As data from the ACEs study began to circulate, educators sought new ways to help children cope at school. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) formed in 1994 with the goal of establishing evidence based SEL as an essential part of education.

In 1997, CASEL and the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) partnered on Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators, with strategies for SEL programming from preschool through grade 12. “This was the first book of its kind,” CASEL states, “and it laid the foundation for the country to begin addressing the ‘missing piece’ in education.”

CASEL helped fund a February 2017 report about SEL training for teachers. To Reach the Students, Teach the Teachers examines SEL as an aspect of teacher certification and concludes that higher education has more work to do to make sure teachers are prepared:

“The implications for good teaching, and for the implementation of SEL in particular, make it clear there’s serious work to be done. If teachers are not aware of their own social and emotional development and are not taught effective instructional practices for SEL, they are less likely to educate students who thrive in school, careers, and life.”

Toxic stress results from untreated trauma

A 2016 film, Resilience, by KPJR Films, looks at an aspect of trauma called “toxic stress,” which results from exposure to strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, violence, economic hardship, etc.

According to the film’s website, “Toxic stress can trigger hormones that wreak havoc on the brains and bodies of children, putting them at a greater risk for disease, homelessness, prison time, and early death. While the broader impacts of poverty worsen the risk, no segment of society is immune.

“Resilience, however, also chronicles the dawn of a movement that is determined to fight back. Trailblazers in pediatrics, education, and social welfare are using cutting-edge science and field-tested therapies to protect children from the insidious effects of toxic stress—and the dark legacy of a childhood that no child would choose.”

Tip: Ask about a teacher’s experience and training in SEL

Family caregivers can ask school staff what they know about trauma-informed instruction and how their own knowledge and training in SEL informs their strategies when teaching a class or a specific student.

Collaborate with the teacher to consider whether an approach at home might match what’s being used in the educational setting. Common responses and phrases will reinforce a child’s emerging SEL skills and provide predictability, which is evidence-based to comfort and calm children.

What does trauma-informed instruction mean?

Generally, trauma-informed instructional techniques help children understand their emotions, describe what is happening, and make skillful decisions about what to do next.

An agency called Edutopia provides an article that lists some common misunderstanding about trauma-informed instruction. One is that children with trauma in their past need to be “fixed.”

“Our kids are not broken, but our systems are,” the article by elementary principal Mathew Portell states. “Operating in a trauma-informed way does not fix children; it is aimed at fixing broken and unjust systems and structures that alienate and discard students who are marginalized.”

Portell, whose Nashville, Tenn., school has been spotlighted as a leader in trauma-informed strategies, points out also that staff are not acting as therapists. “Our part in helping students with trauma is focusing on relationships, just as we do with all of our students. The strong, stable, and nurturing relationships that we build with our students and families can serve as a conduit for healing.”

A trauma-informed instructor might use a specific tool to help the child label an episode of dysregulation, such as the Zones of Regulation, which encourage self-observation and emotional awareness. Another good example is the “brain-hand model” described by Dan Siegel, a well-known neurobiologist and author who has helped lead a movement toward science-informed practices. PAVE provides a video demonstrating the technique to avoid “flipping your lid.”

Here’s how to make and use a hand model of the brain:

- Hold up your hand. The base of your open palm represents the brain stem, where basic functions like digestion and breathing are regulated.

- Cross your thumb over your palm. This represents the central brain (amygdala), where emotions process.

- Fold your four fingers down over your thumb. They represent your frontal cortex, where problem-solving and learning happen.

- Imagine something emotional triggers you and begin to flutter or lift your fingers.

- When you “flip your lid,” the fingers pop up all the way while emotions based in the amygdala rule. Problem behaviors may become probable as you try to cope with fight/flight instincts based in the autonomic nervous system.

- Practice even, steady breathing to regulate the nervous system, and slowly settle the fingers back over the thumb.

- As your fingers fold down, consider what the mind feels like when problem-solving is accessible versus how it feels when emotions disrupt clear thinking.

- Consider how this hand model might help you or someone else recognize and manage an emotional moment.

SEL builds resilience and reduces need for discipline

A Washington agency that teaches self-awareness and resiliency is Sound Discipline, a non-profit based in Seattle. Begun by pediatrician Jody McVittie, Sound Discipline trains about 5,000 educators and parents each year, estimating to impact more than 100,000 children annually.

Like similar programs, Sound Discipline describes “problem” behaviors as coping mechanisms. Acting out is a child’s attempt to manage stress or confusing emotions, and stern punishments can re-ignite the trauma, making the behavior worse instead of better.

A principal goal is to train professionals and parents to collaborate with students in problem solving. Helping a student repair damage from a behavior incident, for example, teaches resilience and develops mental agility. “Children don’t want to be inappropriate,” McVittie emphasizes. “They are doing the best they can in the moment.”

Educational outcomes improve dramatically when students can manage themselves socially and emotionally. A measure of the impact is a reduction in suspensions and expulsions. A 2016 report from the Child Mind Institute shows that proactively teaching restorative discipline reduces school suspensions and drop-out rates:

“Restorative Discipline/Justice includes strategies to both prevent children from breaking the rules and intervene after an infraction has occurred. Some elements are focused on reducing the likelihood of student rule breaking (proactive circles where students and teachers talk about their feelings and expectations) and others on intervening afterwards (e.g., restorative conferences where the parties talk about what happened). In all cases the focus is on avoiding punishment for the sake of punishment.”

Trauma toolkits for educators and families

As part of its materials for school staff and families, OSPI provides a handout that focuses on culturally responsive SEL approaches. The handout states, “Culturally responsive practices are intentional in critically examining power and privilege, implicit biases, and institutional racism, which serve as barriers to realizing the full potential of transformative social emotional learning (SEL) practices.”

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN.org) provides articles about evidence-based practices for adults supporting children with a wide range of circumstances. The website includes links specifically for military families, for example, and includes content related to early learning, homeless youth, and for families and educators supporting children with intellectual and developmental disabilities who also have experienced trauma (I/DD Toolkit).

Adults need self-care and their own SEL to support children

Family caregivers play an important role in furthering trauma-informed approaches by learning about and healing their own trauma experiences, applying trauma-informed principles in their parenting and by learning how to talk about these approaches with schools.

According to Lee Collyer, OSPI’s program supervisor for special education and student support, adults may need to consider their own escalation cycles and develop a personal plan for self-control to support children. Collyer helped develop a three-part video training series for parents, especially while children are learning from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. PAVE provides a short article describing the video series, with links to each section: Webinars offer Parent Training to Support Behavior during Continuous Learning.

In Spring 2020, PAVE launched a series of mindfulness videos with short practices for all ages and abilities and an article with self-care strategies: Stay-Home Help: Get Organized, Feel Big Feelings, Breathe.

PAVE provides a list of resource links to specifically support families during the coronavirus pandemic, including this one: Washington Listens is a program to support anyone in Washington State experiencing stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For anonymous support, call 1-833-681-0211, Mon.– Fri., 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and weekends 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. TTY and language access services are available.

A Brief Overview

- Understanding trauma and providing consistent skill building in Social Emotional Learning (SEL) can improve outcomes in education and elsewhere.

- Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction provides free SEL training materials for educators and families on its website: k12.wa.us.

- Trauma-informed adults can use specific strategies to help children understand their emotions, describe what is happening, and make skillful decisions about what to do next. Read on for ideas about what works.

- Family caregivers can ask school staff what they know about trauma-informed instruction and how their own knowledge and training in SEL informs their strategies when teaching a class or a specific student.

Full Article

“Being at school in a traumatized state is like playing chess in a hurricane.” This statement, from Mount Vernon high-school teacher Kenneth Fox, provides a vivid reminder that learning is not just about academics. Effective social interactions and emotional regulation are critical lifelong skills.

Fox’s quote is highlighted in a free guidebook offered by Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI): The Heart of Learning and Teaching: Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success.

OSPI also provides SEL learning activities for families and educators. OSPI addresses family caregivers directly to describe the resource: “SEL provides skills to do things like cope with feelings, set goals, and get along with others. You can help your kids work on these skills at home and have some fun along the way. It’s important to discuss the SEL skill that will be addressed in the activity (e.g., kindness, empathy, self-exploration, decision-making) to make the activity more focused and targeted on that skill.”

Statewide SEL initiatives have been boosted by a sequence of legislative actions. The 2015 legislature directed OSPI to convene an SEL Benchmarks workgroup, and subsequent bills supported development of SEL learning standards. Information about the history of the work is available through OSPI’s website: k12.wa.us. PAVE provides an article with an overview of the SEL standards and more: State Standards Guide Social Emotional Learning for all Ages and Abilities

Trauma-Informed instruction starts with SEL support for educators

Movement toward Social Emotional Learning (SEL) has grown from knowledge that trauma profoundly impacts educational outcomes. In the 1990s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released findings about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which leave children less resilient and less able to manage their behavior.

Dr. Vincent Felitti, then CDC chief of preventive medicine, boldly proclaimed childhood trauma a national health crisis. The report led to development of an ACEs survey, which scores a person’s likelihood of suffering lifelong physical and mental health impairments resulting from trauma. An ACEs score of 4, the study found, makes a child 32 times more likely to have behavior problems at school.

As data from the ACEs study began to circulate, educators sought new ways to help children cope at school. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) formed in 1994 with the goal of establishing evidence based SEL as an essential part of education.

In 1997, CASEL and the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) partnered on Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators, with strategies for SEL programming from preschool through grade 12. “This was the first book of its kind,” CASEL states, “and it laid the foundation for the country to begin addressing the ‘missing piece’ in education.”

CASEL helped fund a February 2017 report about SEL training for teachers. To Reach the Students, Teach the Teachers examines SEL as an aspect of teacher certification and concludes that higher education has more work to do to make sure teachers are prepared:

“The implications for good teaching, and for the implementation of SEL in particular, make it clear there’s serious work to be done. If teachers are not aware of their own social and emotional development and are not taught effective instructional practices for SEL, they are less likely to educate students who thrive in school, careers, and life.”

Toxic stress results from untreated trauma

A 2016 film, Resilience, by KPJR Films, looks at an aspect of trauma called “toxic stress,” which results from exposure to strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, violence, economic hardship, etc.

According to the film’s website, “Toxic stress can trigger hormones that wreak havoc on the brains and bodies of children, putting them at a greater risk for disease, homelessness, prison time, and early death. While the broader impacts of poverty worsen the risk, no segment of society is immune.

“Resilience, however, also chronicles the dawn of a movement that is determined to fight back. Trailblazers in pediatrics, education, and social welfare are using cutting-edge science and field-tested therapies to protect children from the insidious effects of toxic stress—and the dark legacy of a childhood that no child would choose.”

Tip: Ask about a teacher’s experience and training in SEL

Family caregivers can ask school staff what they know about trauma-informed instruction and how their own knowledge and training in SEL informs their strategies when teaching a class or a specific student.

Collaborate with the teacher to consider whether an approach at home might match what’s being used in the educational setting. Common responses and phrases will reinforce a child’s emerging SEL skills and provide predictability, which is evidence-based to comfort and calm children.

What does trauma-informed instruction mean?

Generally, trauma-informed instructional techniques help children understand their emotions, describe what is happening, and make skillful decisions about what to do next.

An agency called Edutopia provides an article that lists some common misunderstanding about trauma-informed instruction. One is that children with trauma in their past need to be “fixed.”

“Our kids are not broken, but our systems are,” the article by elementary principal Mathew Portell states. “Operating in a trauma-informed way does not fix children; it is aimed at fixing broken and unjust systems and structures that alienate and discard students who are marginalized.”

Portell, whose Nashville, Tenn., school has been spotlighted as a leader in trauma-informed strategies, points out also that staff are not acting as therapists. “Our part in helping students with trauma is focusing on relationships, just as we do with all of our students. The strong, stable, and nurturing relationships that we build with our students and families can serve as a conduit for healing.”

A trauma-informed instructor might use a specific tool to help the child label an episode of dysregulation, such as the Zones of Regulation, which encourage self-observation and emotional awareness. Another good example is the “brain-hand model” described by Dan Siegel, a well-known neurobiologist and author who has helped lead a movement toward science-informed practices. PAVE provides a video demonstrating the technique to avoid “flipping your lid.”

Here’s how to make and use a hand model of the brain:

- Hold up your hand. The base of your open palm represents the brain stem, where basic functions like digestion and breathing are regulated.

- Cross your thumb over your palm. This represents the central brain (amygdala), where emotions process.

- Fold your four fingers down over your thumb. They represent your frontal cortex, where problem-solving and learning happen.

- Imagine something emotional triggers you and begin to flutter or lift your fingers.

- When you “flip your lid,” the fingers pop up all the way while emotions based in the amygdala rule. Problem behaviors may become probable as you try to cope with fight/flight instincts based in the autonomic nervous system.

- Practice even, steady breathing to regulate the nervous system, and slowly settle the fingers back over the thumb.

- As your fingers fold down, consider what the mind feels like when problem-solving is accessible versus how it feels when emotions disrupt clear thinking.

- Consider how this hand model might help you or someone else recognize and manage an emotional moment.

SEL builds resilience and reduces need for discipline

A Washington agency that teaches self-awareness and resiliency is Sound Discipline, a non-profit based in Seattle. Begun by pediatrician Jody McVittie, Sound Discipline trains about 5,000 educators and parents each year, estimating to impact more than 100,000 children annually.

Like similar programs, Sound Discipline describes “problem” behaviors as coping mechanisms. Acting out is a child’s attempt to manage stress or confusing emotions, and stern punishments can re-ignite the trauma, making the behavior worse instead of better.

A principal goal is to train professionals and parents to collaborate with students in problem solving. Helping a student repair damage from a behavior incident, for example, teaches resilience and develops mental agility. “Children don’t want to be inappropriate,” McVittie emphasizes. “They are doing the best they can in the moment.”

Educational outcomes improve dramatically when students can manage themselves socially and emotionally. A measure of the impact is a reduction in suspensions and expulsions. A 2016 report from the Child Mind Institute shows that proactively teaching restorative discipline reduces school suspensions and drop-out rates:

“Restorative Discipline/Justice includes strategies to both prevent children from breaking the rules and intervene after an infraction has occurred. Some elements are focused on reducing the likelihood of student rule breaking (proactive circles where students and teachers talk about their feelings and expectations) and others on intervening afterwards (e.g., restorative conferences where the parties talk about what happened). In all cases the focus is on avoiding punishment for the sake of punishment.”

Trauma toolkits for educators and families

As part of its materials for school staff and families, OSPI provides a handout that focuses on culturally responsive SEL approaches. The handout states, “Culturally responsive practices are intentional in critically examining power and privilege, implicit biases, and institutional racism, which serve as barriers to realizing the full potential of transformative social emotional learning (SEL) practices.”

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN.org) provides articles about evidence-based practices for adults supporting children with a wide range of circumstances. The website includes links specifically for military families, for example, and includes content related to early learning, homeless youth, and for families and educators supporting children with intellectual and developmental disabilities who also have experienced trauma (I/DD Toolkit).

Adults need self-care and their own SEL to support children

Family caregivers play an important role in furthering trauma-informed approaches by learning about and healing their own trauma experiences, applying trauma-informed principles in their parenting and by learning how to talk about these approaches with schools.

According to Lee Collyer, OSPI’s program supervisor for special education and student support, adults may need to consider their own escalation cycles and develop a personal plan for self-control to support children. Collyer helped develop a three-part video training series for parents, especially while children are learning from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. PAVE provides a short article describing the video series, with links to each section: Webinars offer Parent Training to Support Behavior during Continuous Learning.

In Spring 2020, PAVE launched a series of mindfulness videos with short practices for all ages and abilities and an article with self-care strategies: Stay-Home Help: Get Organized, Feel Big Feelings, Breathe.

PAVE provides a list of resource links to specifically support families during the coronavirus pandemic, including this one: Washington Listens is a program to support anyone in Washington State experiencing stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For anonymous support, call 1-833-681-0211, Mon.– Fri., 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and weekends 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. TTY and language access services are available.

Children with trauma backgrounds can be more ready to learn when adults take time to cultivate feelings of safety and connection first. Neuroscientist Bruce Perry provides a “3 Rs” approach to intervention: Regulate, Relate, and Reason. The Center to Improve Social and Emotional Learning and School Safety provides specific guidance.

PAVE provides a list of resource links to specifically support families during the coronavirus pandemic, including this one: Washington Listens is a program to support anyone in Washington State experiencing stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For anonymous support, call 1-833-681-0211, Mon.– Fri., 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and weekends 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. TTY and language access services are available.