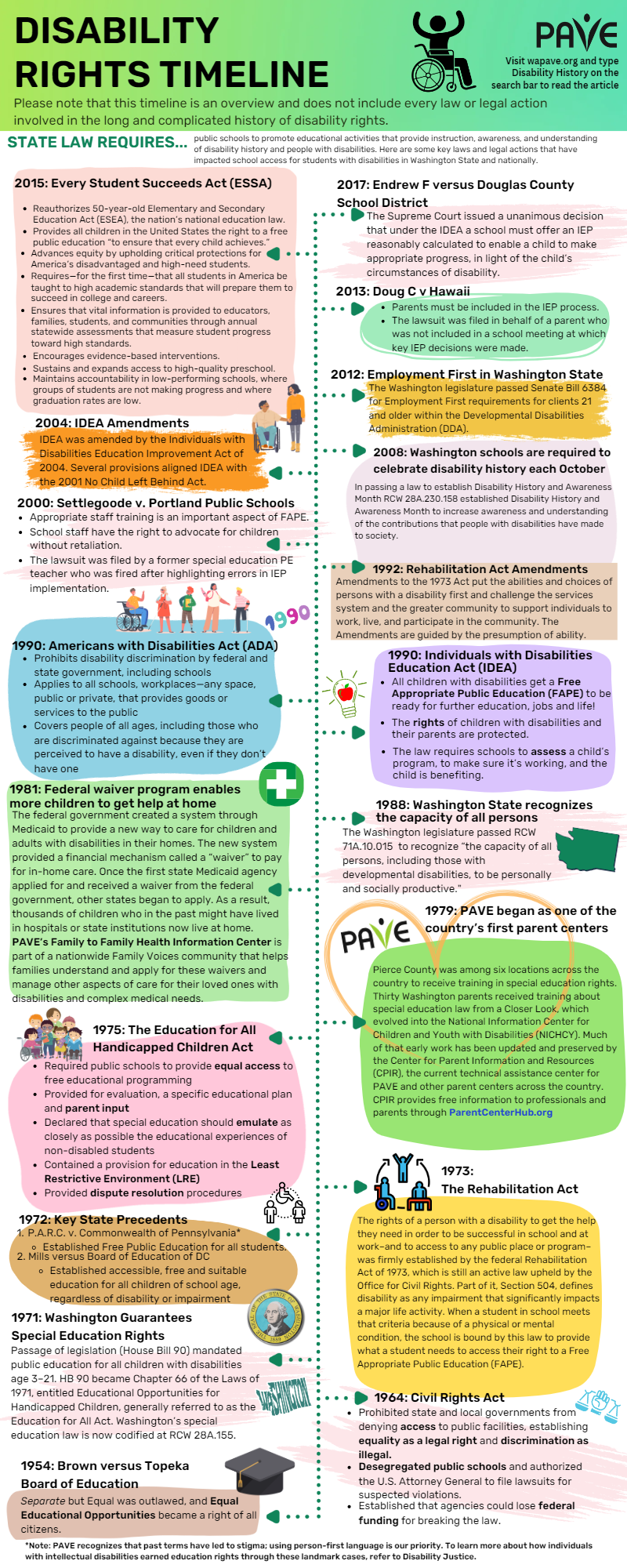

The history of disability rights shows how people with disabilities have worked hard to get equitable access, fair treatment, and meaningful inclusion. Key laws and strong community voices have helped shape education and civil rights. Today, it is as crucial as ever to learn, speak up, and work together to build a more inclusive society.

A Brief Overview

- October is Disability History and Awareness Month in Washington State (RCW 28A.230.158). This month helps people learn about disabilities, raise awareness, promote respect and acceptance, and build pride among individuals with disabilities.

- Federal and state laws, along with court decisions, have helped students with disabilities go to public school, get the services they need, and be included in general education whenever possible.

- State law requires public schools to teach students about disability history and help them understand what it means to live with a disability.

- Parent Centers like PAVE help families and individuals understand disability rights. To find a Parent Center outside of Washington State, visit Find My Center on the Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR) website.

Celebrating the History of Disability Rights

Disability History and Awareness Month in October is a time for students, families, teachers, and community leaders to remember and learn about the disability rights movement. Equity and access are protected by law, but there is still work to be done to make sure that laws are followed so that everyone has fair access to opportunities.

Organizations like PAVE help families and individuals understand disability rights. They also explain how history has shaped today’s laws, including the words we use when we talk about disability rights.

Below is a timeline of key actions at the state and federal level.

Please note that this article is an overview and does not include every law or court case from the long history of disability rights.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

This landmark Supreme Court case was brought by families who challenged racial segregation in public schools. In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), the Court ruled that separating students by race was unfair and violated the 14th Amendment’s promise of equal protection under the law.

‘Separate but equal’was outlawed, and equal educational opportunities became a right of all citizens.

The decision helped establish the principle that all students deserve equal educational opportunities. It became a foundation for future disability rights cases. Advocates used this ruling to argue that students with disabilities also have the right to attend public schools and receive a fair education.

1964: Civil Rights Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a major law that helped protect people from discrimination. It made it illegal for state and local governments to deny access to public places, like schools, parks, and libraries. This law confirmed that equality is a legal right, and that discrimination is against the law.

It also helped desegregate public schools and gave the U.S. Attorney General the power to take legal action against schools or other public agencies suspected of breaking the law. It also stated that agencies that didn’t follow the law could lose their federal funding.

1971: Washington guarantees special education rights

In 1971, the small but fierce Education for All Committee — Evelyn Chapman, Katie Dolan, Janet Taggart, Cecile Lindquist — worked with two law students to craft and advocate for passage of legislation (House Bill 90) to mandate public education for all children with disabilities age 3–21. HB 90 became Chapter 66 of the Laws of 1971, entitled Educational Opportunities for Handicapped Children, generally referred to as the Education for All Act. Washington’s special education law is now codified at RCW 28A.155.

1972: Key precedents are established in other states

In P.A.R.C. v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1971)*, a group of parents went to court to fight for their children’s right to go to public school. At the time, some schools didn’t allow children with disabilities to attend. The court decided that all children, no matter their abilities, have the right to a free public education.

A few months later, Mills v. Board of Education of the District of Columbia (1972) built on the P.A.R.C. decision. In Mills, the court found that education should not only be free and accessible to all students, but also suitable for each child’s needs. These two cases helped establish the principle that all children, regardless of ability, have the right to attend public school and receive an education suited to their individual needs.

To learn more about how individuals with intellectual disabilities gained education rights through these landmark cases, visit Disability Justice.

*Note: PAVE recognizes that past terminology has contributed to stigma. We are committed to using inclusive, disability-affirming language that reflects the preferences of individuals and communities, including identity-first and person-first approaches.

1973: The Rehabilitation Act

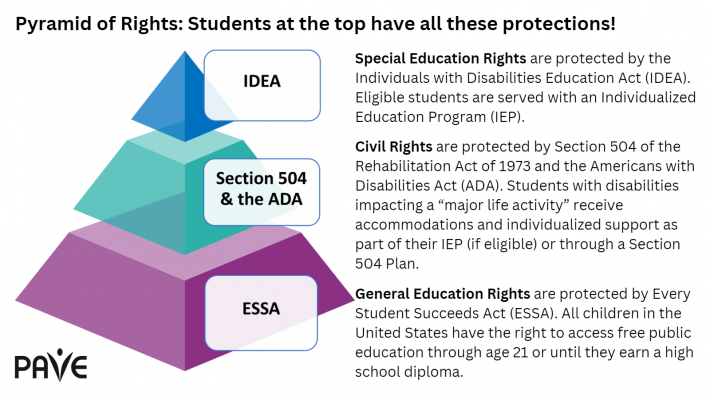

The rights of people with disabilities to get the help they need in order to be successful in school, at work, and in any public place or program was firmly established by the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This federal law that is still active today and enforced by the Office for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education. Part of it, Section 504, defines a disability as any condition that seriously affects a major life activity. If a student has a physical or mental condition that meets this definition, the school must follow the law and provide support to help the student access their education and participate in school activities.

1975: The Education for All Handicapped Children Act

In 1975, the U.S. passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, the first federal law focused on the education of children with disabilities. It required public schools to give students with disabilities equal access to free educational programming, along with evaluations, a specific learning plan, and input from parents. The law said that special education should emulate the learning experiences of students without disabilities as closely as possible. This means that students with disabilities have the right to a school experience that looks as much like a typical student’s program as possible. It also introduced the idea of the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE), encouraging schools to work harder to include students of many abilities in general education classrooms. To help families resolve disagreements with the school, the law outlined required dispute resolution procedures. Parents are given information about their rights through Procedural Safeguards that are shared at IEP and other official meetings.

1979: PAVE began as one of the country’s first six parent centers

Pierce County was among six locations across the country to receive training in Special Education rights. In 1979, thirty Washington parents received training on Special Education law. The goal was for those parents to share information throughout the state. To help this movement, a clearinghouse named Closer Look provided intense training for these pioneering parents about the laws. Closer Look evolved in the National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities (NICHCY), and much of that work has been updated and preserved by the Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR), the current technical assistance center for PAVE and other parent centers across the country. CPIR continues to provide free information to professionals and parents about education rights under federal law.

To connect with a Parent Center outside Washington State, visit Find My Center on the Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR) website.

1981: Federal waiver program enables more children to get help at home

The federal government created a system through Medicaid to provide a new way to care for children and adults with disabilities in their homes. This system introduced a funding option called a waiver, which helps pay for in-home support. Once the first state Medicaid agency applied for and received a waiver from the federal government, other states began to apply. As a result, thousands of children who might have lived in hospitals or institutions in the past are now able to live at home. PAVE’s Family to Family Health Information Center is part of a nationwide Family Voices community that helps families understand and apply for these waivers and manage other aspects of care for their loved ones with disabilities and complex medical needs.

1988: Washington State recognizes the capacity of all persons

The Washington legislature passed RCW 71A.10.015 to recognize “the capacity of all persons, including those with developmental disabilities, to be personally and socially productive.

“The legislature further recognizes the state’s obligation to provide aid to persons with developmental disabilities through a uniform, coordinated system of services to enable them to achieve a greater measure of independence and fulfillment and to enjoy all rights and privileges under the Constitution and laws of the United States and the state of Washington.”

1990: Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) protects people from disability discrimination by the federal and state governments, including public schools. It also applies to all schools, workplaces, and any public or private place that offers goods or services to the public. The law covers people of all ages, including those who are treated unfairly because they are perceived to have a disability, even if they don’t have one.

Many ADA protections are like those found in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Both laws focus on equity and access, and they protect people with disabilities throughout their lifespan.

Understood.org offers resources for parents to learn about ADA protections in schools, including printable fact sheets. The U.S. Department of Justice provides an ADA Information Line to answer questions and help people report possible violations of the law. The Office for Civil Rights also provides guidance for students with disabilities as they plan for post-high school education programs.

1990: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act was renamed and enacted as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990. Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)came into being, which is still key to how schools support students with disabilities. FAPE means that every child with a disability has the right to an education that helps prepare them for further learning, work, and life. The law also protects the rights of students and their parents or guardians. Schools are required to check if a student’s program is working and make sure the student is making progress.

IDEA is an entitlement law, which means students with unique needs must get support based on their individual situation—not just what’s already available. This federal law guides how each state creates its own special education rules. In Washington State, those rules are found in the Washington Administrative Code (WAC), specifically in chapter 392-172A. Title 34, Part 104, is a federal rule that protects people from discrimination and is enforced by the Office for Civil Rights.

1992: Rehabilitation Act Amendments

Amendments to the 1973 Rehabilitation Act focus on the abilities and choices of persons with disabilities. These changes challenge service systems and communities to support individuals as they work, live, and participate in the community. The Amendments are guided by the idea of a presumption of ability. This means that every person with a disability, regardless of the severity of the disability, can achieve employment and other rehabilitation goals, if they have the right services and support.

The primary responsibilities of the vocational rehabilitation system include:

- Help individuals with disabilities make informed choices about jobs that lead to integration and inclusion in the community.

- Develop an individualized rehabilitation program with the full participation of the person with a disability.

- Match a person’s needs and interests with appropriate services and supports.

- Work closely with other agencies and programs, including school districts, to build a strong and unified support system.

- Focus on quality services and ensure service representatives honor the dignity, participation, and growth of each person as they explore employment options.

2000: Settlegoode v. Portland Public Schools

In 2000, the case of Settlegoode v. Portland Public Schools helped bring attention to the rights of teachers who work in special education. A former special education PE teacher filed the lawsuit after being fired for speaking up about problems with how IEPs were being followed. The court ruled that appropriate staff training is an important part of FAPE and that school staff have the right to stand up for students without being punished.

2004: IDEA Amendments

Congress updated IDEA by passing the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA) in 2004. Some parts of the law were changed to match the goals of the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act. Here are a few examples of updates:

- IDEIA allowed 15 states to try out 3-year IEPs when parents agreed every year as a pilot program.

- Based on a report of the President’s Commission on Excellence in Special Education, the law changed the requirements for evaluating children with learning disabilities.

- New rules were added about how schools handle discipline for students in special education. These updates continue to shape discipline policies in Washington State.

- The law strengthened the idea of Least Restrictive Environment (LRE), saying students should learn in regular classrooms with extra help and services, “to the maximum extent appropriate.”

2008: Washington schools are required to celebrate disability history each October

Washington State passed a law to create Disability History and Awareness Month (RCW 28A.230.158), which takes place every October. The legislature explained that: “annually recognizing disability history throughout our entire public educational system, from kindergarten through grade twelve and at our colleges and universities, during the month of October will help to increase awareness and understanding of the contributions that people with disabilities in our state, nation, and the world have made to our society. The legislature further finds that recognizing disability history will increase respect and promote acceptance and inclusion of people with disabilities. The legislature further finds that recognizing disability history will inspire students with disabilities to feel a greater sense of pride, reduce harassment and bullying, and help keep students with disabilities in school.”

2012: Employment First in Washington State

The Washington legislature passed Senate Bill 6384 to create Employment First requirements people age 21 and older who receive services through the Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA). The law states, “The program should emphasize support for the clients so that they are able to participate in activities that integrate them into their community and support independent living and skills.”

The legislation:

- Supports employment as the first choice for adults of working age.

- Incorporates the right to transition to a community access program after nine months in an employment service.

- Clarifies that a client receive only one service option at a time (employment or community access).

A DDA Policy Document describes the history behind the law and the rules for how it would be implemented.

2013: Doug C. v Hawaii

In Doug C. v. Hawaii (2013), the court ruled that parents must be included in the IEP. The lawsuit was filed in behalf of a parent who was not included in a school meeting at which important decisions were made about their child’s IEP. The decision confirmed that families have a legal right to be part of planning their child’s education and that schools must make sure parents and guardians are involved.

2015: Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

In 2015, Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) to update the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which had been the nation’s main education law for over 50 years. ESSA says that every child in the United States has the right to a free public education “to ensure that every child achieves.”

The law:

- Protects the rights of disadvantaged and high-need students.

- Requires for the first time that all students be taught to high academic standards that prepare them for college and careers.

- Provides important information to families, educators, and communities through yearly statewide tests that show student progress toward high standards.

- Encourages schools to use evidence-based strategies to support learning.

- Expands access to high-quality preschool.

- Keeps schools accountable when student groups are not making progress or graduation rates are low.

2017: Endrew F v. Douglas County School District

In Endrew F., the Court ruled that schools must offer an IEP that is reasonably calculated to enable a child to make progress, based on their individual circumstances of disability. The decision rejected the old “de minimis standard,” which allowed schools to offer only minimal progress. Trivial progress is no longer enough.

The ruling emphasized:

- Grade-level goals for students who can learn in the general education classroom.

- Parent participation in the IEP process.

- Higher expectations for student growth under IDEA.

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice John G. Roberts explained that a child making only small gains would be like “sitting idly… awaiting the time when they were old enough to drop out.” The case continues to influence how schools and agencies support students with disabilities, and many professionals encourage families to hold schools accountable to these higher standards.

PAVE provides more information about parent and guardian rights to participate in their child’s education in this article: Parent Participation in Special Education Process is a Priority Under Federal Law .