For families new to Washington State, this article includes state-specific information about special education systems. PAVE wants to extend a warm welcome to your entire family and to let you know that we are ready to support you. If your family has moved here to fulfill a military role, we thank you for your service!

The language of special education, school and support systems differ between States. Following is some basic information to help you navigate Washington systems.

Brief overview

- The article provides state-specific information about special education and medical systems in Washington State.

- Washington’s education system includes the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), 295 independent school districts, and nine Educational Service Districts (ESDs).

- Washington has adopted the Interstate Compact on Educational Opportunity for Military Children (commonly known as “MIC3”) to address school transition issues for military children, with a state commissioner overseeing compliance.

- Children in Washington must begin attending school by age 8 and continue until age 18, with some special exceptions. Washington offers multiple pathways to graduation and requires a High School and Beyond Plan for all students.

- The Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) administers the state early intervention services (EIS) program, called Early Services for Infants and Toddlers (ESIT) for infants and toddlers with disabilities or delays.

- Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP) is a no-cost prekindergarten program for 3- and 4-year-old children from families facing significant challenges.

- Washington school districts must respond to special education evaluation requests within 25 school days and complete evaluations within 35 school days. IEPs must be implemented within 30 days of eligibility determination, with transition plans required by age 16.

- Washington’s Medicaid program, Apple Health, provides health plan options, with TRICARE as the primary payee for military families.

- Welcome to Washington!

Welcome to Washington!

Whether your family is newly stationed in Washington or returning after time away, we welcome you! Moving to a new state is a big change, and it can be confusing when programs and services are called different names than they were in your last location. We’re here to help you learn how Washington’s education and medical systems work, so you can find the right support for your child.

This video shares key facts to help you get started in Washington with a child who has exceptional needs.

The School System

The State Education Agency (SEA) is the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). Local Education Agencies (LEAs) are organized as 295 Districts that operate independently and include a school board governance structure. School boards are responsible to follow the Open Public Meetings Act. There are nine Educational Service Districts (ESDs) that partner with OSPI to provide services for school districts and communities and to help OSPI implement legislatively-supported education initiatives.

Charter schools, as public schools, have the same responsibilities as all public and non-public entities when serving students with disabilities. This includes developing and implementing Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or Section 504 Plans for eligible students.

Washington has adopted the Interstate Compact on Educational Opportunity for Military Children (commonly known as “MIC3”), which addresses certain school transition issues for military children consistently, from State to State. Each Member State has a MIC3 State Commissioner to oversee compliance and coordinate with other commissioners as needed. Parents of military-connected children may contact their School Liaison or MIC3 State Commissioner directly for support with Compact-related issues. PAVE has prepared a MIC3 Step-by-Step Checklist to Resolve Issues with the Interstate Compact.

Washington’s Purple Star Award Program recognizes school districts that go above and beyond to support military families. Districts with this award provide a webpage with resources, have a trained staff member to help, and make sure teachers understand school transition rules under the Interstate Compact. Families can look for the Purple Star designation when choosing schools—it’s a sign the district is committed to welcoming military-connected students. To see which districts have the award, visit OSPI’s Purple Star page.

Washington’s compulsory attendance law requires that children begin attending school full-time at the age of 8 and continue attending regularly until the age of 18 (RCW 28A.225.010). A child must have turned 5 years old by August 31 to enroll in kindergarten, and 6 years old to enroll in first grade. Military-connected children who are covered by the provisions of MIC3 may continue kindergarten or first grade, despite the school’s age requirement, if they were already enrolled and attending at the sending school in their previous state. This PAVE article explains how MIC3 supports children in military families with enrollment-related issues.

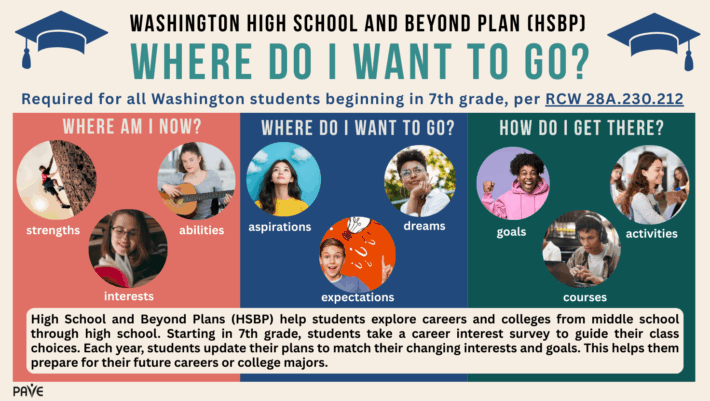

Washington has multiple Pathways to Graduation and requires a High School and Beyond Plan (a career and college exploration experience that students begin in seventh grade) for all students. Under MIC3, schools must place military children in courses and programs based on placement and assessments performed by the sending school. Schools and districts may waive course requirements for placement and/or graduation of military-connected children, if a child has met the sending school’s requirements for grade advancement, placement, or graduation. Learn more about how MIC3 protects academic progress toward graduation in this PAVE article.

Early Learning Programs (ages 0-5)

Families concerned about a child’s development can call the Family Health Hotline at 1-800-322-2588, with support in multiple languages, or complete a free developmental screening online at ParentHelp123. The Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) administers the state early intervention services (EIS) program, called Early Services for Infants and Toddlers (ESIT). After evaluating a child for eligibility and developing a family-focused plan, ESIT provides services to help infants and toddlers with disabilities or delays to learn and catch up in their development. Planning for the child’s transition out of ESIT by their third birthday includes coordination with the local school district to evaluate the child for school-aged services and supports. PAVE’s toolkit for family caregivers of infants and toddlers, From Birth to Three, outlines the educational rights of children and families in early intervention services.

The Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP) is Washington’s no-cost prekindergarten program, aimed at preparing 3- and 4-year-old children from families facing more significant challenges for success in school and life. Families with children aged 3 or 4 by August 31st may be eligible for ECEAP. Children are eligible for ECEAP and Head Start based on their age and family income. Up to 10 percent of ECEAP and Head Start children can be from families above the income limit if they have certain developmental factors or environmental factors such as homelessness, family violence, chemical dependency, foster care, or incarcerated parents. PAVE’s 3-5 Transition Toolkit includes more information and resources to support families of children with disabilities in this age range.

Special Education Information (School age)

Every student with a disability is protected from discrimination under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, including each student with a 504 Plan and each student with an Individualized Education Program (IEP). OSPI provides fact sheets about Section 504 in multiple languages that describe the evaluation process and state requirements. Parents may contact the Section 504/Civil Rights compliance officer assigned to their student’s school district.

Washington Administrative Code (WAC), implements the provisions of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in WAC Chapter 392-172A. Parents’ rights and responsibilities in special education, known as procedural safeguards, are described in a short handbook available for download in multiple languages on OSPI’s website.

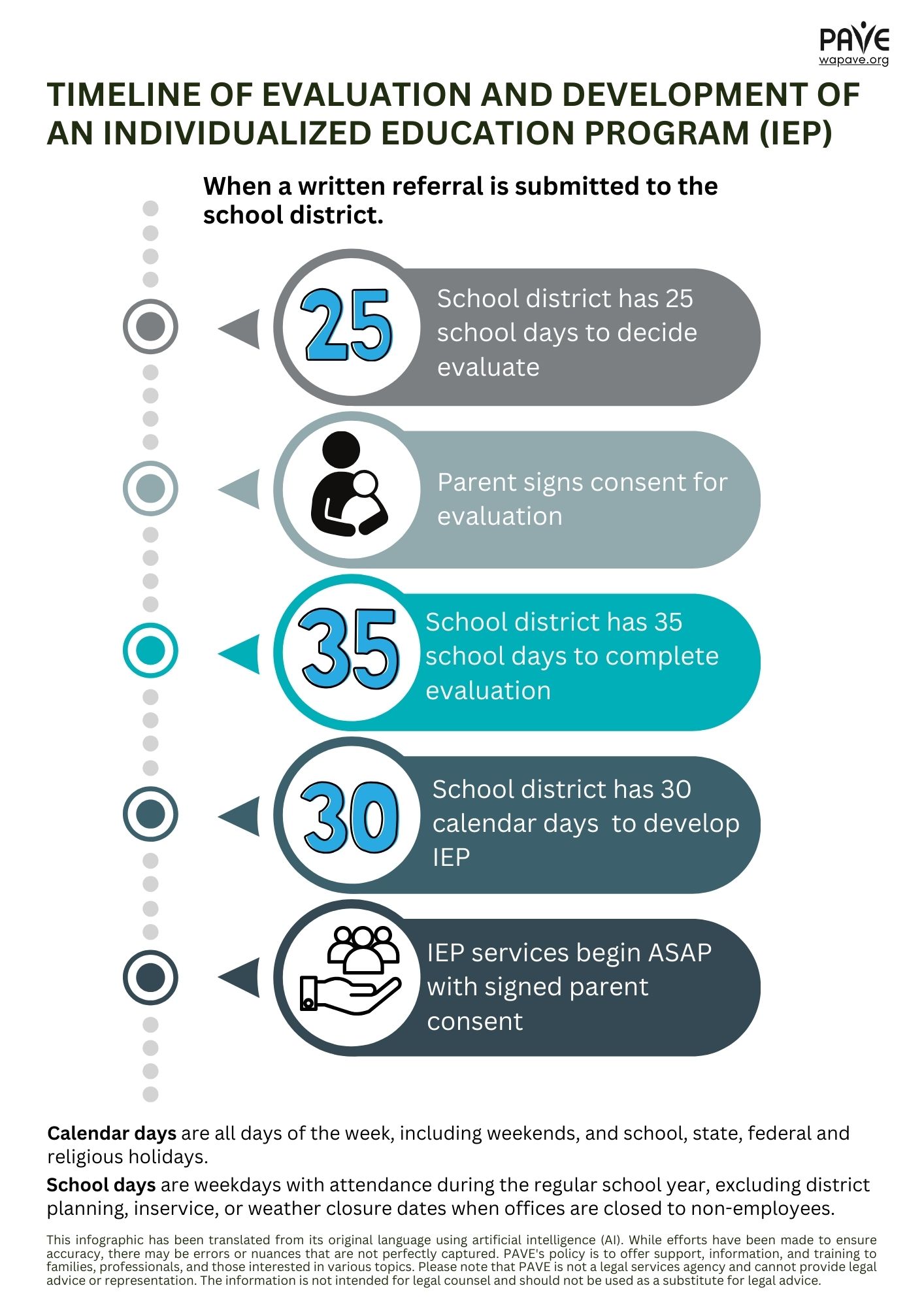

A child’s right to a timely evaluation and the school district’s responsibility to seek out and serve students with disabilities, referred to as Child Find, is described on OSPI’s website. A school district has 25 school days to respond to a referral/request for special education evaluation. Once a parent/caregiver signs consent to evaluate, the district has 35 school days to complete the evaluation. A parent can request an evaluation any time there are concerns about whether services match the student’s present levels of performance and support needs. PTI provides a sample letter for requesting evaluation.

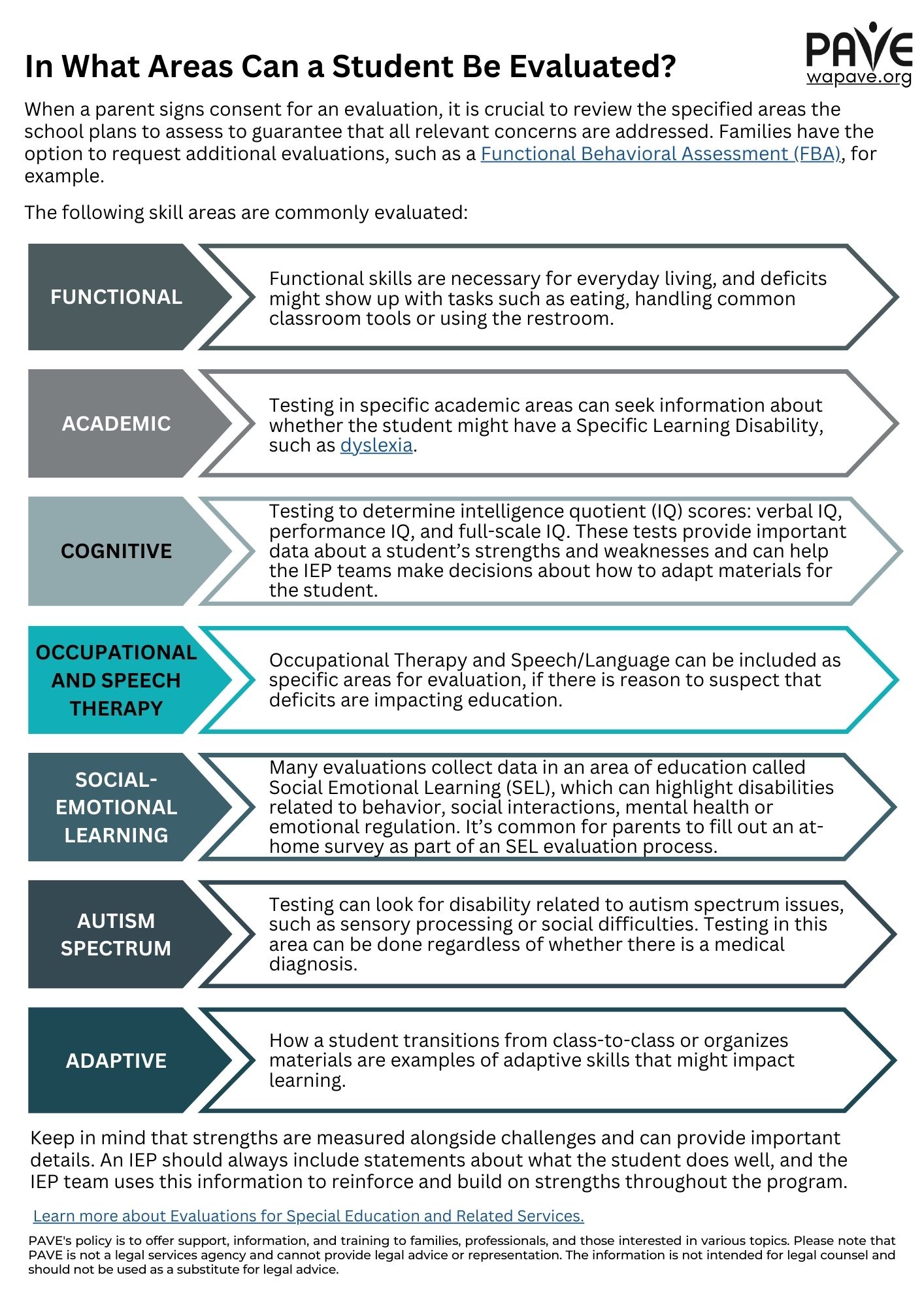

Areas of evaluation are associated with 14 eligibility categories. Developmental Delay is a category for children ages 0-9 years old. The category of Emotional/Behavior Disability is unique to Washington – it is known as Emotional Disturbance under IDEA. Washington law requires that schools screen children in kindergarten through second grade for signs of dyslexia and to provide reading support for those who need it.

School districts must write and implement an IEP within 30 calendar days after eligibility is determined. Decisions about the provision of special education services are made by an IEP team, which includes parents and specific required staff members (WAC 392-172A-03095).

For a student with an IEP, there must be a transition plan in place by the beginning of the year in which they turn 16 years of age, unless the IEP deems it appropriate to begin earlier. Students “age out” of special education when they graduate from high school with a diploma or at the end of the school year in which they turn 21 years of age. If the student’s birthday is after August 31 of the current school year, they may continue special education until the end of that school year.

In 2019, the Washington State Legislature provided students with multiple pathways to graduation by passing House Bill (HB) 1599. PAVE provides an on-demand webinar on this topic: Life After High School: A Two-Part Training to Help Families and Young People Get Ready.

OSPI offers both informal and formal dispute resolution processes. IEP facilitation is available at no cost through Sound Options Group as a voluntary and informal process where a neutral facilitator helps parents and schools resolve special education concerns collaboratively. Washington State Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds (OEO) acts as a neutral guide to help parents and schools resolve disagreements about special education services, without providing legal advice or advocacy. OSPI provides three formal special education dispute resolution processes: mediation, special education community complaint, and due process hearing.

In addition to educational resources, families often need healthcare support. Washington offers options that work alongside TRICARE benefits to meet your child’s needs.

Medical Supports and Services

Washington’s Medicaid, which includes the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHiP), is called Apple Health. Applications are managed through the Health Care Authority (HCA), which oversees various Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to provide health plan options. Open enrollment for Medicaid and Medicare starts on November 1st, 2025 and ends on January 15th, 2026. This is the annual opportunity to sign up, renew, or change coverage to best suit your family’s situation. Washington Health Plan Finder has step-by-step instructions for applying and navigators to help with the application process. Help is available for those who are having trouble navigating the health insurance landscape.

Eligible dependents of military families can benefit from both TRICARE and Medicaid. When a military family member is dually enrolled in TRICARE and Medicaid, TRICARE is the primary payee and Medicaid covers remaining costs. When a service member leaves the military and TRICARE benefits change, Medicaid can provide services similar to those of TRICARE Extended Care Health Option (ECHO).

TRICARE allows beneficiaries to make changes to their health coverage when a Qualifying Life Event (QLE) occurs, such as a move to a new city, region, or zip code. When a QLE happens, you generally have 90 days from the date of the move to update your enrollment.

In addition to QLEs, TRICARE offers an annual open season for making changes to health coverage. Open season starts on the second Monday in November and ends on the second Monday in December each year. Any changes made during this period take effect January 1 of the following year. During open season, families can:

- Stay in their current plan – no action required.

- Enroll in a new plan.

- Switch between plans.

- Change enrollment type from individual to family coverage, or vice versa.

PAVE provides more information about TRICARE’s basic plans, ECHO, and the Autism Care Demonstration in the TRICARE’s Big Three on-demand module. For this and more personalized learning at your own pace, check out our PAVE Learning Library.

Learn More

PAVE offers downloadable toolkits filled with fact sheets, worksheets, sample letters, and practical tips to guide you through every stage of your child’s education and care. These resources are designed to make complex systems easier to understand and navigate.

Celebrate your military child all year long with social stories, activities, and tools that help families stay connected and ease transitions. The PAVE article, Purple Up! Celebrating the Month of the Military Child, includes free downloads in the top five languages spoken in military households.

Want to know what makes a military family “exceptional”? Explore PAVE’s two-part series on the Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP) to learn how enrollment works and what supports are available to help your family thrive.

STOMP (Specialized Training of Military Parents) workshops and webinars offer military families the opportunity to access valuable information and resources while fostering connections and knowledge-sharing to create a collaborative environment that strengthens partnerships between families and professionals. STOMP events are free to military-connected families from all branches of services, including all service statuses and all installations worldwide.

Need personalized help? Military families can access one-on-one support, training, information, and resources through PAVE’s Get Support request form — wherever the military takes you!