A Brief Overview

- Dyslexia is a common condition that makes it hard to work with language. Reading difficulties are one sign of dyslexia.

- Washington passed a law in 2018 requiring schools to screen young children for indicators of dyslexia. The law took effect in the 2021-22 school year.

- Dyslexia is a Specific Learning Disability. Students with learning disabilities are eligible for an Individualized Education Program (IEP) if they demonstrate a need for Specially Designed Instruction (SDI). SDI is key when a student isn’t keeping up with grade-level work and standard teaching strategies aren’t working.

- The Revised Code of Washington (RCW 320.260) requires schools to support literacy with “multi-tiered” programming. That means schools provide different levels of help for all students who need it, regardless of special education eligibility.

- Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) has handouts about dyslexia screening and supports in WA Schools, some in multiple languages.

[ ខ្មែរ (Khmer), 한국인(Korean), ਪੰਜਾਬੀ (Punjabi), Русский (Russian), Soomaali (Somali), Español (Spanish), Filipino/Tagalog, 中國人(Traditional Chinese), and Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)] They are listed at the end of this article.

Full Article

A child who struggles to read can quickly fall behind in school. Nearly every learning area includes some reading, and children might become confused or frustrated when they don’t get help to make sense of their schoolwork. Behavior challenges can result, and sometimes schools and families struggle to understand why the student is having a hard time. Reading difficulties affect a student’s literacy. One definition of literacy is the ability to read, write, speak and listen in ways that let people communicate well. The Revised Code of Washington (RCW 320.260) requires schools to support literacy with “multi-tiered” programming to help with reading difficulties.

One cause of difficulty with reading is a specific learning disability called dyslexia. The state’s definition of dyslexia, adopted in 2018, is similar to a definition promoted by the International Dyslexia Association. According to Washington State’s definition:

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disorder that is neurological in origin and that is characterized by unexpected difficulties with accurate or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities that are not consistent with the person’s intelligence, motivation, and sensory capabilities.”

Understood.org provides a video and additional materials to learn about dyslexia. Here’s their plain language definition: “Dyslexia is a common condition that makes it hard to work with language.”

Washington State requires dyslexia screenings (tests to find out if a student may have or be at risk for dyslexia) and interventions (help with reading). Lawmakers in 2018 passed Senate Bill 6162 to require schools to screen children from kindergarten through second grade using state-recommended literacy screening tools. The law took effect in 2021-22.

Since reading is used in almost every learning area, this law means schools have a duty to identify students who show signs of possible dyslexia while they are in their early reading years. The law also requires schools to provide “interventions” (help) to students identified through the screening.

OSPI offers a Fact Sheet about the screening in multiple languages. It includes the reason for the screening, who gives the screening, the skills that are screened, the process, and information about dyslexia.

What happens if the screening shows indicators (signs) of dyslexia?

The law requires the school to:

- Notify the student’s family of the identified indicators and areas of weakness

- Share with the family the school’s plan for multitiered systems of support to provide supports and interventions (help with reading)

- The notice should include resources and information about dyslexia for the family’s use.

- Update families regularly on the student’s progress

How can families tell if a student has trouble, or may have trouble with reading and language? Families can look for these signs in children who are toddlers and pre-kindergarten:

- Trouble learning simple rhymes

- Speech delays

- following direction

- Difficulty reading short words or leave them out

- Trouble understanding the difference between left and right

-Child Mind Institute Parent Guide to Dyslexia.

Screening happens in kindergarten through grade 2. If a student is already older than that, families can check for these signs of reading and language difficulty at home.

Understood.org states: “Dyslexia can also cause trouble with spelling, speaking, and writing. So, signs can show up in a few areas, not just in reading.” Understood.org lists these signs for students older than grade 2: Signs a Student May Have Dyslexia (handout)

The Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) offers a Family and Caregiver Discussion Guide that may help when families are planning to speak to their child’s teacher or school administrators about their student’s reading difficulties, behavior, or other concerns.

What happens if the screening shows a student has signs of dyslexia, or if families or teachers notice signs and want a student to get help?

The school puts multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) into action. “Multi-tiered systems” usually means beginning reading help as part of regular classroom reading instruction. If a student’s reading difficulties continue, the student may get more intensive instruction in smaller groups, and perhaps move up to intensive one-on-one time with a reading instructor. For any of these levels, the reading instruction must be “evidence-based” methods which means the methods have been tested and shown to be useful in helping with reading difficulties.

This guide for schools from OSPI has details about MTSS.

These more intensive levels of reading help may work very well. Not every reading difficulty is due to dyslexia, and not every person with dyslexia has the same level or type of reading difficulty.

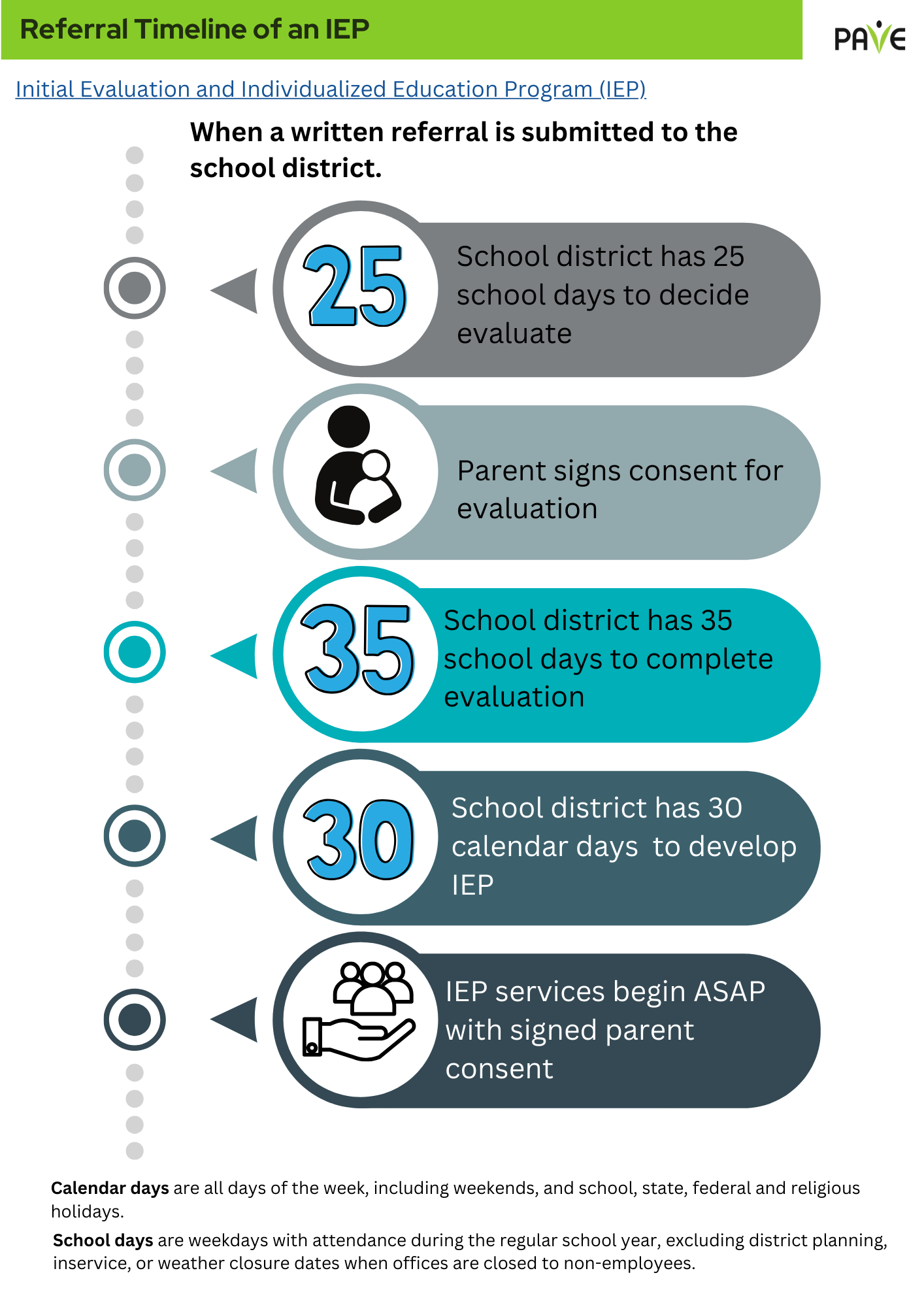

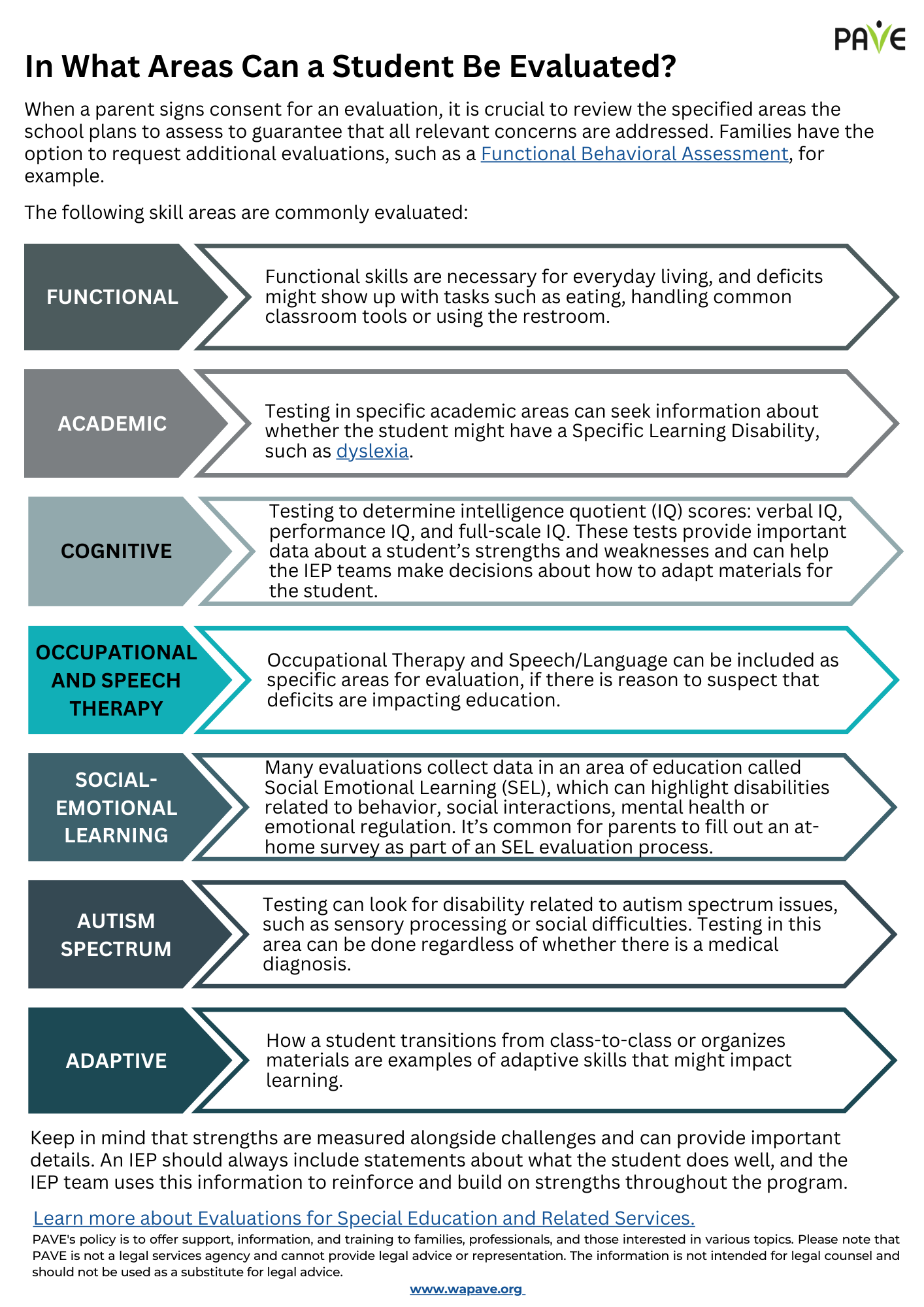

At any point during these interventions, families or teachers may see a student is not making progress and ask that the student be evaluated for special education to see if the student qualifies for an Individualized Education Program (IEP). An IEP can provide Specially Designed Instruction (SDI), which means instruction will be based on the student’s unique needs and provide extra instructional time, assistive technology, and other supports.

The federal law that provides special education eligibility and funding is called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). According to the IDEA, Dyslexia is a Specific Learning Disability. Specific Learning Disability is a category of eligibility for an Individualized Education Program (IEP). IDEA states that students have the right to a Free, Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), and the IEP is a key factor in a student having FAPE.

What types of help can a student get with reading and literacy?

Multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) use instruction methods that have been proven to work for many students, starting with help in the general (regular) classroom. If a student doesn’t make progress that way, the student may join a smaller group for that gives each student more time with a teacher or reading specialist and even move on to one-to-one instruction with a reading specialist. These options are available to any student who shows signs of dyslexia or reading difficulty. OSPI offers Dyslexia Guidance (for schools): Implementing MTSS for Literacy with more specific information.

IEP: Students can get Specially Designed Instruction (SDI) based on their unique needs, such as particular areas of language and literacy where they have difficulties. Reading programs offered by the school can be included in an IEP. IEPs can include accommodations, which may include texts and instructions in audio format, text-to-speech/speech to text software, recording oral answers to assignment or test questions, access to distraction-free location for reading, allowing extra time to complete work or tests, and many more. Accommodations for Students with Dyslexia by the International Dyslexia Association lists many other options.

Section 504 Plan: Section 504 plans don’t include Specially Designed Instruction. They do include accommodations.

The National Center on Improving Literacy has information on when a Section 504 plan may make sense for a student with reading difficulties or dyslexia. They note that Section 504 Plans, which fall under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, do not provide for Specially Designed Instruction. If a student’s reading has improved without an IEP by receiving multitiered systems of support, a Section 504 plan may offer Assistive Technology options, spelling checks, extended time on assignments and testing and other accommodations.

Interventions (help with reading) are schoolwide

Not all students who need reading support will need IEPs or a Section 504 Plan. The Revised Code of Washington (RCW 320.260) requires schools to support literacy through “evidence-based multi-tiered” programming. That means schools provide different levels of support for all students who need help, whether or not the student has an IEP or Section 504 Plan.

Some schools have reading programs funded by Title 1, which is part of a federal law called Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Title 1 is funded to close opportunity gaps related to poverty and other measures.

TIP: Ask about all options for reading support at your school. If a student with an IEP participates in a schoolwide reading program, then the IEP can list that program as part of the student’s services.

Dyslexia can be identified and helped without a diagnosis

Students do not need a diagnosis of dyslexia to be evaluated (tested) for special education eligibility. If the family has concerns, they can ask the school to evaluate the student. Requests should be in writing. PAVE provides a sample letter to help families request an educational evaluation.

Here’s a sentence to include in the evaluation request letter:

“I need my child tested for a specific learning disability. I believe there is a problem with reading that is disability related.”

TIP: When a student’s need for reading help qualifies for an IEP, there are important things that families need to know about how IEPs work, what the goals are for the student’s reading abilities, what type of reading help will be given, where the Specially Designed Instruction will take place, and what the parent’s and student’s roles and responsibilities are when their student has an IEP. These are the basics:

- IEP Eligibility is based on a student’s needs

- Specially Designed Instruction (SDI) serves the identified needs

- The IEP tracks learning progress with specific goals in each area of SDI

What options do families have if they disagree with a school’s decisions about their student’s reading supports or other decisions?

- If a student has not been screened for signs of dyslexia and the family has concerns, a first step is to meet with the student’s teacher. This article by the International Dyslexia Association offers specific steps families can take.

- Families can request an evaluation to see if the student qualifies for an IEP or a Section 504 Plan.

- If families disagree with the evaluation, they can request an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE) from a provider outside the school. This article from PAVE gives steps and a sample letter to request and IEE: Evaluations Part 2: Next Steps if the School Says ‘No’

- If the student has an IEP, this article gives specific steps to follow: Parents as Team Partners: Options When You Don’t Agree with the School.

- For students with a Section 504 Plan, OSPI recommends:

“The Section 504 coordinator in each district makes sure students with disabilities receive the accommodations they need and respond to allegations of discrimination based on disability. [Section 504 coordinators are members of a school’s Section 504 team which develops 504 Plans to accommodate a child’s needs]. A discussion with your school principal, or Section 504 coordinator at the school district, is often the best step to address your concerns or disagreements about Section 504 and work toward a solution. Share what happened and let the principal or coordinator know what they can do to help resolve the problem. If you cannot resolve the concern or disagreement this way, you can file a complaint.”

What else to know:

Keep in mind that families and schools don’t need to use the term dyslexia at all. They can talk about a student’s learning disability in reading, writing, or math in broader terms such as “Specific Learning Disability.” Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), dyslexia is a Specific Learning Disability that qualifies a student for special education.

Specific Learning Disability is defined by the Washington Administrative Code (WAC 392-172A-01035):

“Specific learning disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia, that adversely affects a student’s educational performance.”

The state’s definition of learning disability excludes “learning problems that are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of intellectual disability, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage.”

Here’s a handout on Accommodations and Modifications for Students with Dyslexia.

Resources

Special Education is a Service, Not a Place

Student Rights, IEP, Section 504 and More (video)

Steps to Read, Understand, and Develop an Initial IEP

Supporting literacy: Text-to-Speech and IEP goal setting for students with learning disabilities

IEP Tips: Evaluation, Present Levels, SMART goals

Section 504: A Plan for Equity, Access and Accommodations

Evaluations Part 2: Next Steps if the School Says ‘No’

There’s more: just type “Special Education,” “IEP” or “504” in the search bar

From OSPI:

Family and Caregiver Discussion Guide with Educators and Schools

Understand Literacy Screening: Parents and Families

Available in ខ្មែរ (Khmer), 한국인(Korean), ਪੰਜਾਬੀ (Punjabi), Русский (Russian), Soomaali (Somali), Español (Spanish), Filipino/Tagalog, 中國人(Traditional Chinese), and Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

Best Practices for Supporting Grades 3 and Above

Section 504 & Students with Disabilities (web page)

Dyslexia Guidance (for schools): Implementing MTSS for Literacy

Dyslexia awareness is promoted by the National Center on Improving Literacy (NCIL), which provides resources designed to support families, teachers, and policy makers. On its website, the agency includes state-specific information, recommends screening tools and interventions and provides research data about early intervention.

- NCIL provides a unique resource in the format of an online or downloadable comic book: Adventures in Reading Comic Books stars Kayla, a girl with dyslexia.

- Georgetown University’s Director of the Center for the Study of Learning provides a researcher’s perspective: What do we know about what’s different in the brain of a person with dyslexia?

- A psychology professor from the University of Wisconsin-Madison discusses early intervention: What has scientific research taught us about how children learn to read?

- A TEDx talk called The True Gifts of a Dyslexic Mind features Dean Bragonier describing how dyslexia impacts the brain.

- Your Guide to Dyslexia in English and Spanish, Oregon Branch of International Dyslexia Association

The International Dyslexia Association has many detailed resources for families.